The Face

of Poverty

The hardships of the complex humanitarian emergency that have beaten Venezuela while Nicolás Maduro holds the reins of the State have been growing stronger by the day. Poverty has come to stay at Venezuelan homes and its eviction seems utopic.

This is reflected by the National Survey of Living Conditions (ENCOVI for its acronym in Spanish) published by the Andrés Bello Catholic University. Lack of official records on the social and economic realities of this country have turned this survey over time into a statistical beacon.

The 2019-2020 edition results are dramatic. It is estimated that 96.3% households in Venezuela live on income poverty. Poor food consumption is a trend that continues to grow as only 3% of the population is food secure. The Venezuelan crisis has wiped out social class distinctions altogether. As such, multidimensional poverty has grown from 51% in 2018 to 64.8% in 2019.

These are not cold numbers, merely the reality behind more than 30,000 testimonies taken by hundreds of pollsters who visited more than 10,000 households across Venezuela. These are the voices of the survey takers who stared at the post cards of a country and found that 79.3% of its people do not have enough money to pay for basic goods. Where at least 1 in every 4 homes suffers from severe food insecurity and where 639,000 children under the age of 5 suffer from chronic malnutrition.

Data is always a cause for concern but it takes on new meaning when someone tells the story behind it. This report contains the accounts of those people who spent months staring directly at the face of poverty, listening to every sobbing mother who confessed she had nothing to feed her children with.

The 2019-2020 ENCOVI survey was drawn up by every door that was opened to the pollsters, including those in remote and rural places. With every visit came a new story. With luck, the following interview would be less depressing than the one before.

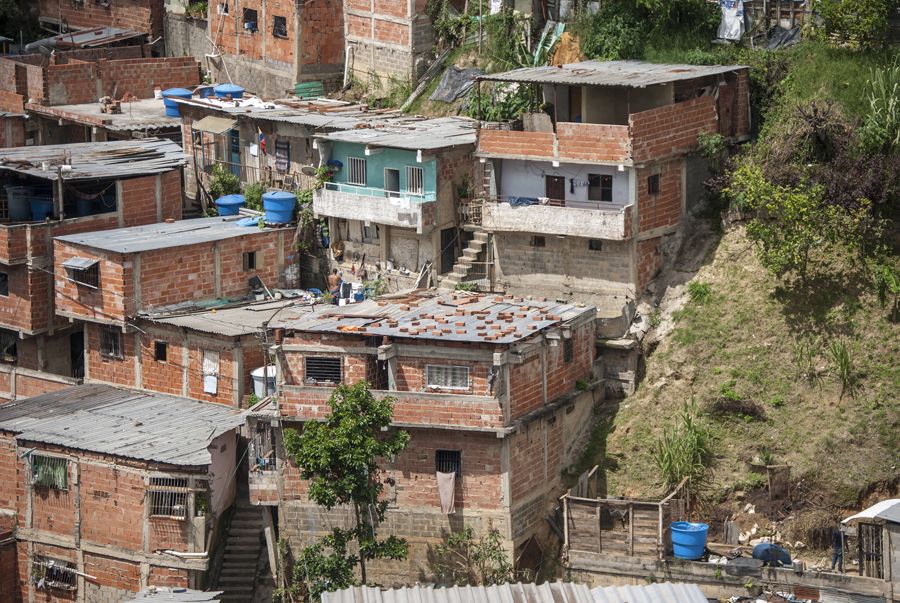

In Carabobo, homes are cramped with children who do not go to school (Courtesy of Marian Serrano)

In Carabobo, homes are cramped with children who do not go to school (Courtesy of Marian Serrano)

Face to Face

“Poverty looks at you straight in the eye”, says Nelson Martínez, a 45 year old Chemistry professor. He is talking about his first encounter face to face with poverty. Before becoming an ENCOVI survey taker for the 2019-2020 edition, he had only seen that level of misery in photographs from countries undergoing an official humanitarian crisis. Little did he know he would find it several times over in his native land of Yaracuy.

In the many communities he visited, Nelson began to notice common patterns, beginning with children running around dirt roads in their underwear. It only took one person to notice the arrival of those survey takers who came to town loaded with questions to spread the word around. Invitations into homes was persistent as people were under the assumption that the visit would ensure them a bag of food or some sort of economic benefit.

A similar incident happened at Los Cañizos, a shantytown in Veroes, Yaracuy. “This place seemed as though it did not belong in Venezuela. We saw children with overgrown heads and bellies, practically abandoned houses and overcrowded dwellings”, says Martínez. He recounts the story of an interview he had with a 56 year old woman who lived with her three children and twelve grandchildren in an old house subsidized by the governments of the so-called “IV Republic”. Another two children had gone abroad and hardly sent her any money. Her youngest go to school only when it is certain that they will be fed. If not, “it doesn’t make sense for them to go”, she said.

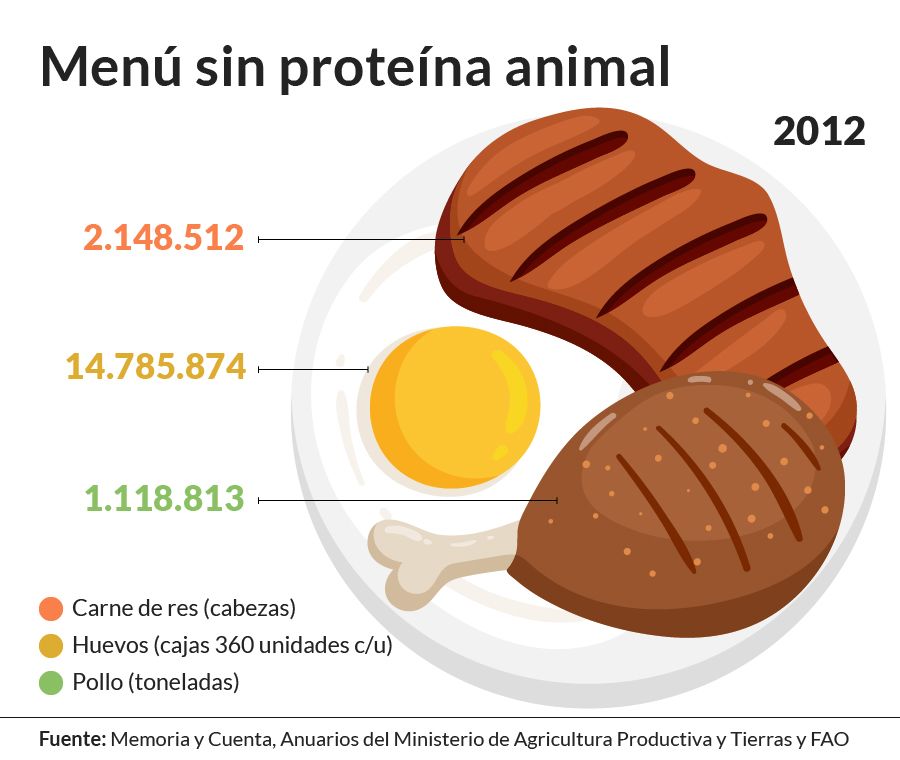

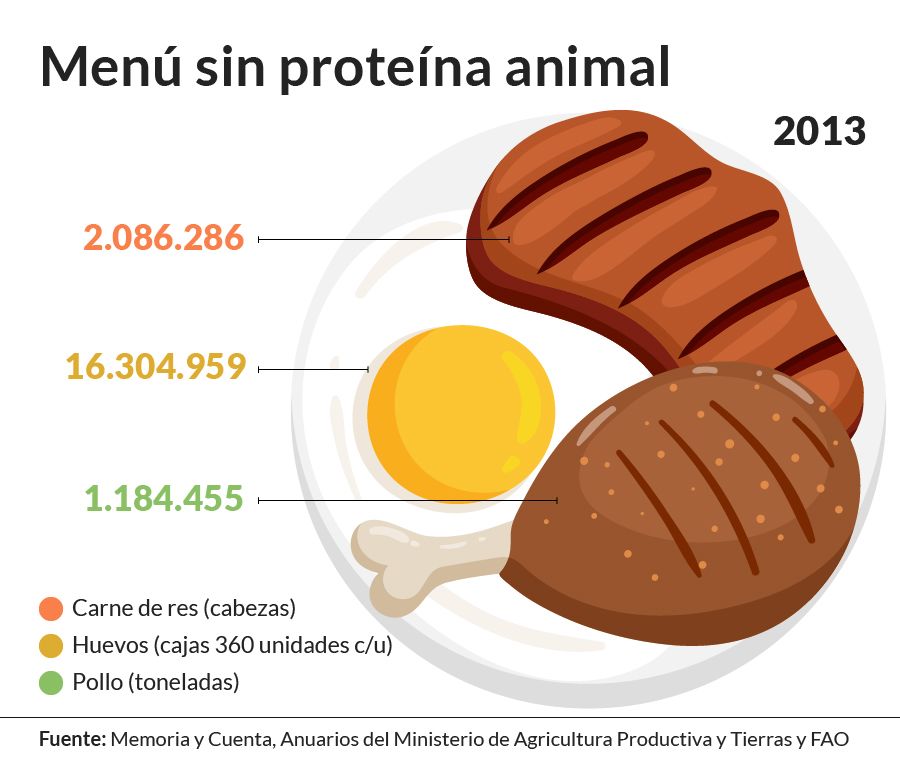

One of the surveys requirements, with due parental consent, was to measure and weigh all children under the age of five. This data reflects the impact of hunger. In the food consumption segment of the interview, Martínez asked questions such as: “How much meat did you buy?”; “How often do you consume protein?”; “What types of food do you eat on a weekly basis?”; and “Do you think you are getting a proper nourishment?”. The responses were astounding. In interviews he held towards the end of 2019, there were people who admitted having spent more than 90 days without eating meat. In February 2020, other people told him they had not consumed protein since the beginning of the year.

Survey takers in Carabobo found places that reminded them of images from Africa or Haiti (Courtesy of Marian Serrano)

Survey takers in Carabobo found places that reminded them of images from Africa or Haiti (Courtesy of Marian Serrano)

Nelson Martinez says that the shock with reality was progressive. The more disturbing stories he and his team heard, the more they wanted to help. Alas, they couldn’t do much. This university professor adds that there were places where people seemed to be dying of want. He tells the story of a 70 year old man he visited at his home. The man lived alone and was in the late stages of cancer. The first thing the man wanted to know was if he would get access to chemotherapy if he answered the survey. Martínez was left in disbelief.

He also witnessed the living conditions in rural areas around Yaracuy. There were homes where people ate and slept on the floor because they did not own a table or a bed. In others, there were septic tanks or latrines instead of toilets. Dirt floors, adobe walls, lack of gas, wooden stoves, intermittent electricity and scarce water supply were common.

In August 2019, the survey’s regional team began to compile data on what was known as the “town’s catacombs” in order to determine an action plan to draw up a sort of census in homes that they would later visit for the complete survey interview. A first stage would imply getting acquainted with the area and locate and identify every head of household as well as determine the number of inhabitants living together.

This was Martinez’s first time as an ENCOVI survey taker and he certainly paid the price for being a rookie. He had to learn how to handle himself within the powers that the local communal councils have acquired. These councils have become censors and vigilantes of their own neighbors. In Chivacoa, for example, community leaders tried to expel pollsters sent by the Andrés Bello Catholic University (UCAB). When the neighbors protected them, the communal council threatened to call the police or the town’s Mayor, Carmen Suárez, a member of the Venezuelan United Socialist Party (PSUV).

Practically abandoned houses or dwellings that had no more room for other people was part of the panorama found in Yaracuy (Courtesy of Nelson Martínez)

Practically abandoned houses or dwellings that had no more room for other people was part of the panorama found in Yaracuy (Courtesy of Nelson Martínez)

At gunpoint

In the State of Sucre, ENCOVI survey takers were not only forced to report to members of the communal council. Criminal groups also demanded explanations asking pollsters to declare if they worked for the Special Action Forces (FAES) of the Bolivarian National Police (PNB) and if they were affiliated to Nicolas Maduro’s regime or the Venezuelan opposition.

Crime has gone through the roof here, says Carlos Urrieta, a 38 year old attorney. Also working as an ENCOVI survey taker, in 2020 he witnessed how delinquency overrode police forces, at least in those territories located in eastern Venezuela. Urrieta found completely wiped out police units and was warned by officers not to go to certain areas because they would not be able to offer him protection. These are areas where the police cannot enter. Criminal gangs, Urrieta admits, have better arsenal and more control.

In Yaracuy there were people who admitted to having spent more than 90 days without eating meat (Courtesy of Nelson Martínez)

In Yaracuy there were people who admitted to having spent more than 90 days without eating meat (Courtesy of Nelson Martínez)

In Yaguaraparo, Güiria and Irapa, criminal activity prevented the original survey plan of action from being carried out. In San Juan de Unare, two armed men threatened one of the pollsters as he was entering a house to begin an interview and ordered him to abandon town. In Carúpano, while completing a survey interview, a group of men harassed Urrieta, among them the father of the five year old child he had just weighted and measured.

Despite these misgivings, no image is imprinted more in the minds of the pollsters than that of poverty. “I’m no specialist, but I can honestly say we found ourselves face to face with malnutrition. We saw children with chapped lips whose flaky skin was stuck to their bones”, Urrieta reminisces.

While Carlos Urrieta and Nelson Martinez were knocking on doors in Sucre and Yaracuy, Nejhellyt Gil was visiting the Caracas suburbs. These are places that can eradicate whatever standard notion one has of a metropolis or the capital of a country.

This 39 year old elementary school teacher has been working as a survey taker for the past eleven years. This time, she visited around 300 homes in neighborhoods such as 23 de Enero, La Vega, El Paraíso, Los Frailes de Catia, Los Flores de Catia, El Valle, San Martín and El Junquito. What she found in all of them were complexly foreign living conditions in which lack of public services, mainly gas and water, were a common complaint. She also found that many homes cook their meals in a stove using firewood.

In Sucre, communal councils and even criminal groups demanded that pollsters explain the reasons behind their visit (Courtesy of Carlos Urrieta)

In Sucre, communal councils and even criminal groups demanded that pollsters explain the reasons behind their visit (Courtesy of Carlos Urrieta)

Poverty abounds in Caracas and Gil describes it best: there are areas that seem rural but are inside a metropolis.

“We went to places where you could hardly go on foot. There were houses built out of scrap metal and boards, whose walls had collapsed. We went to communities where there was nothing but weeds and structures built on the ground. There was no access to water, the pipes had been damaged for years”, she says.

Meanwhile, Marian Serrano traveled through Puerto Cabello, Guacara, Valencia, Naguanagua, Libertad, Mariara and Morón in Carabobo State. She found places that reminded her of pictures from Africa or Haiti. “I found abuelitos (senior citizens) who had not eaten for two days and children who seemed to suffer from acute malnutrition. What parent wouldn’t break into tears if their child were out on the street asking people who were eating for their leftovers?”

Serrano also witnessed houses filled with up to eight people who liv in spaces which measure no more than 86 or 107 square feet. They had no mattresses to sleep on or money to buy decent food, lacked electric service and had spent months without gas or running water. These were cramped living spaces where children do not go to school and people with chronic diseases have almost impossible access to medicine which, incidentally, they cannot afford.

Serrano adds: “We also found formerly affluent middle class suburbs completely run down by the crisis. These suburbs are now populated by senior citizens who used to have painted houses and a modern car parked in their garage. It was a lifestyle they could afford thanks to their jobs. Today this is a thing of the past”.

People in Táchira live in invaded lands or non-consolidated dwellings and join forces in order to survive (Courtesy of Ana Rondón)

People in Táchira live in invaded lands or non-consolidated dwellings and join forces in order to survive (Courtesy of Ana Rondón)

"I saw the crisis worsen"

Onelsys Suárez, 55, is a teacher who has been working as an ENCOVI survey taker since its creation in 2014. Through the years she has seen not only the multiplication of poverty but also its depths. She realized this in 2016 when she began to talk to people she had already interviewed for previous editions of the survey. “I met people who had grown poorer since the last time I visited them. They had either stayed behind or had no access to opportunities”, she emphasizes.

This time conditions were worse. She met families who barely fed on one banana during the entire day, at best some sort of legume. They did not consume protein.

As many of her fellow survey takers, Suárez was under the impression that she was witnessing a unique situation. In reality, almost all of them were seeing the same situation pan out across Venezuela.

Ana Rondón, a forensic scientist and researcher at the Táchira Social Observatory, registered a pattern that showed the most common traits of poverty: 1) lack of access to basic services; 2) abundance of improvised housing made out of wood and scrap metal; and 3) lack of sewage systems.

Her range of action was in the States of Táchira, Apure and Barinas where 95% of the zones she visited were vulnerable to poverty. Most of them were a product of invasions or non-consolidated dwellings where inhabitants join forces to cover their basic needs, although they all depend on boxes granted by the government sponsored Local Committees for Supply and Production (CLAP for its acronym in Spanish) which contain food that they cook with firewood.

In Barinas, ideological or political tendencies prevented some people from answering the survey questions (Courtesy of Ana Rondón)

In Barinas, ideological or political tendencies prevented some people from answering the survey questions (Courtesy of Ana Rondón)

“I saw people who had grown used to the idea of being unemployed and depend on the CLAP boxes for food. They had grown accustomed to being dirty and having their children underfed. They weren’t worried, they were just fine with what they had and would simply wait for something to be given to them. From what I could tell this is now the new normal. Basically they are families who used to live in the same poverty conditions”, Rondón adds. She also emphasized that these people feel there is no hope for change.

The forensic scientist says that her team was treated far better in the more vulnerable areas. Those who lived in invaded dwellings made an effort to cater to the survey takers, perhaps awaiting some sort of help in exchange but even so after becoming aware that this was not the case. On the contrary, they experienced a less than favorable treatment in neighborhoods or areas with higher social stratum where people even refused to offer data. This is a society who is suspicious and untrustworthy.

The contrasts were most noteworthy in regards to politics. “We had a particular situation in Barinas because most communities in that State are radically prone to the government. They are aware that they are poor but also know that by answering the survey, the government will look bad. Therefore they do not participate. Communal leaders are also opposed to the supply of any data”, Rondón says. And yet, there are some realities which are impossible to hide.

In Venezuela, Poverty is Primed Around Women

The latest data given by the 2019-2020 National Survey on Living Conditions (ENCOVI) indicates that 96% of the Venezuelan population is poor. This reality affects mostly women. The middle class has been completely wiped out and 54% of those surveyed admitted to having recently entered into poverty.

“When I was 11, my younger brothers and I went to our neighbors to ask for food”, says Yolimar López recalling the first time she begged for food. Back in 2012, food was scarce at home and her mother and seven brothers needed to survive. She lived in Cocorote, a rural sector in Miranda State with a population of about 200 families. Houses there are built with cinder blocks, waste material and adobe. None of them have trustworthy basic services; some of them don’t have any services at all.

“We lived in a shack built with scrap metal and ate what we had harvested (corn, beans, yam, corm, bananas). In 2012 we could no longer grow our food because we had no money left. My mother began to work by growing mushrooms but the pay was scarce”. López had to rely on others. This went on for three years.

XXI Century adobe houses can be found just a short distance from Venezuela’s capital city

En pleno siglo XXI y a pocos kilómetros de la capital, aún hay paredes de bahareque

López is now 20 years old. She has a husband and an 18 month old baby. She was unable to complete her studies at “Misión Ribas”, a government funded school. Without teachers to encourage her because there simply were none and with lack of public transportation, she found it hard to go to school and one day dropped out altogether. “It was too hard”, says the young woman who would take between two to three hours to get back and forth.

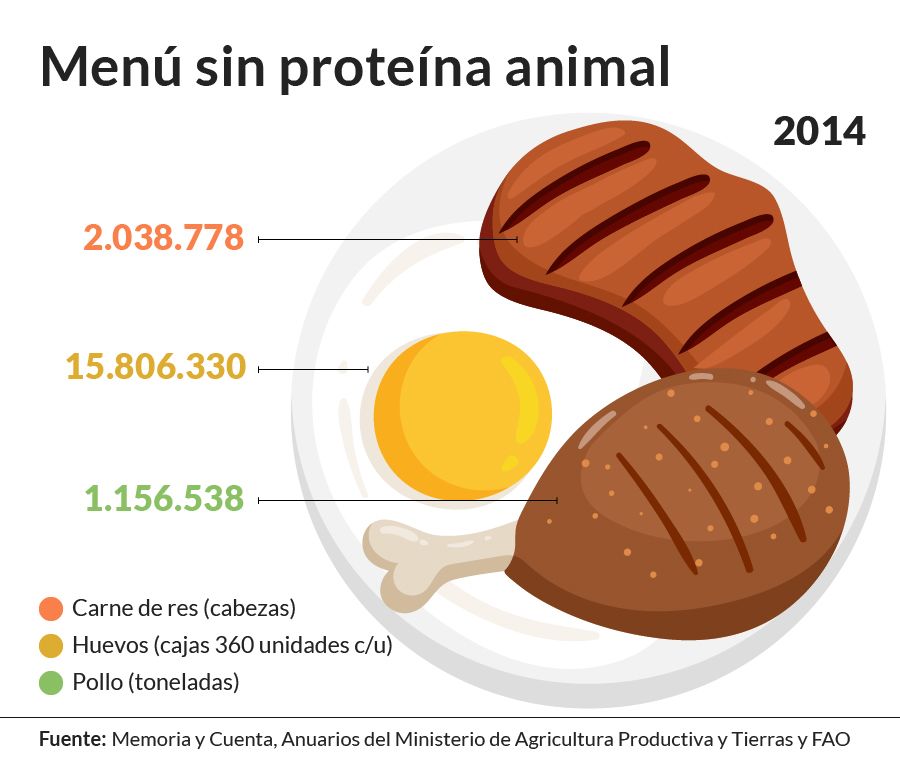

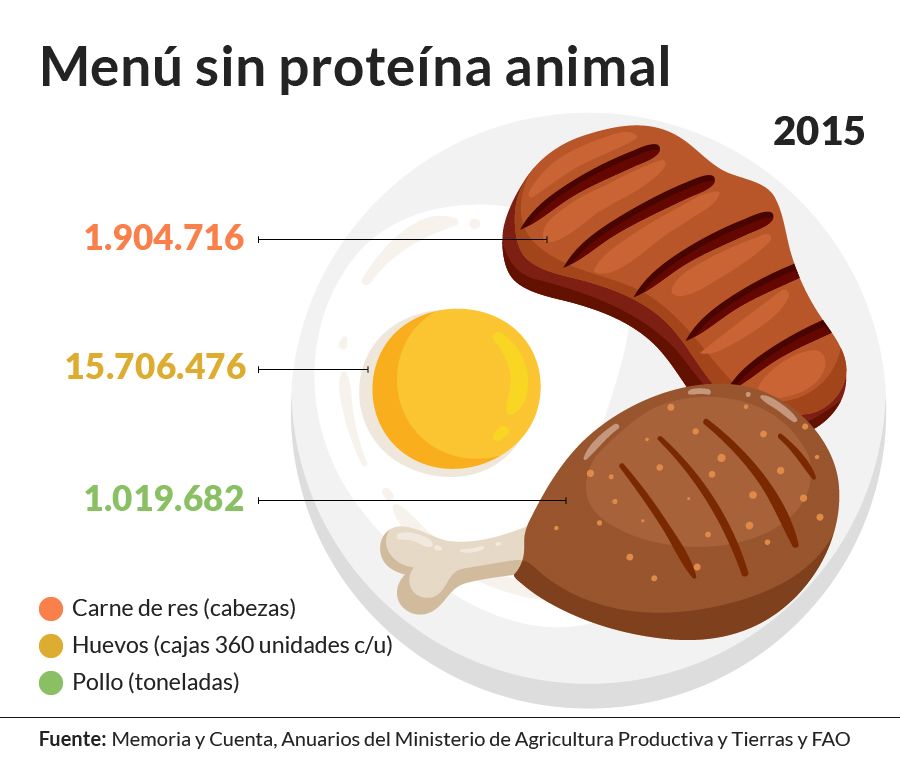

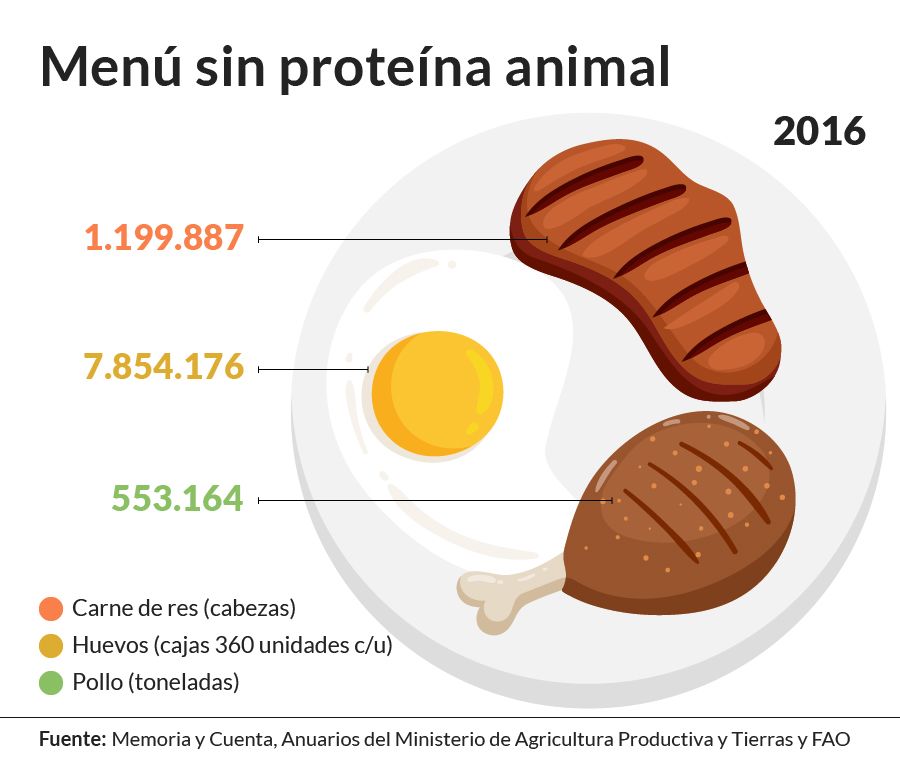

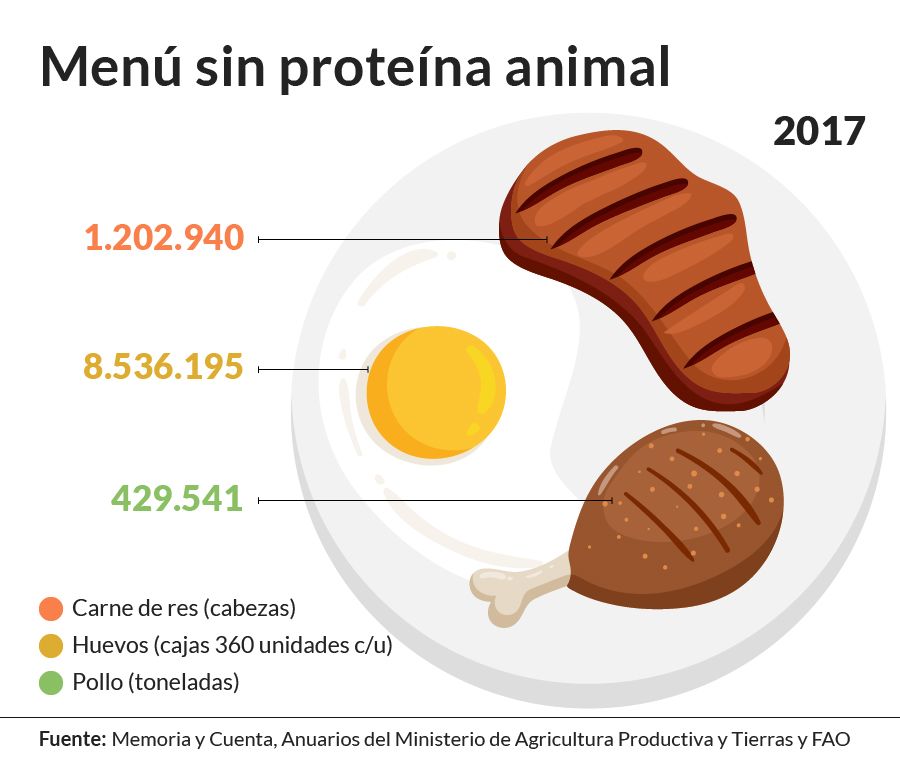

In 2014, hunger forced López out of her home. She was not alone. Beginning that year, Venezuela’s poverty line began to grow exponentially. At the time, 33.1% of Venezuelans lived in complete poverty. By 2019, that figure had grown to 96.2%.

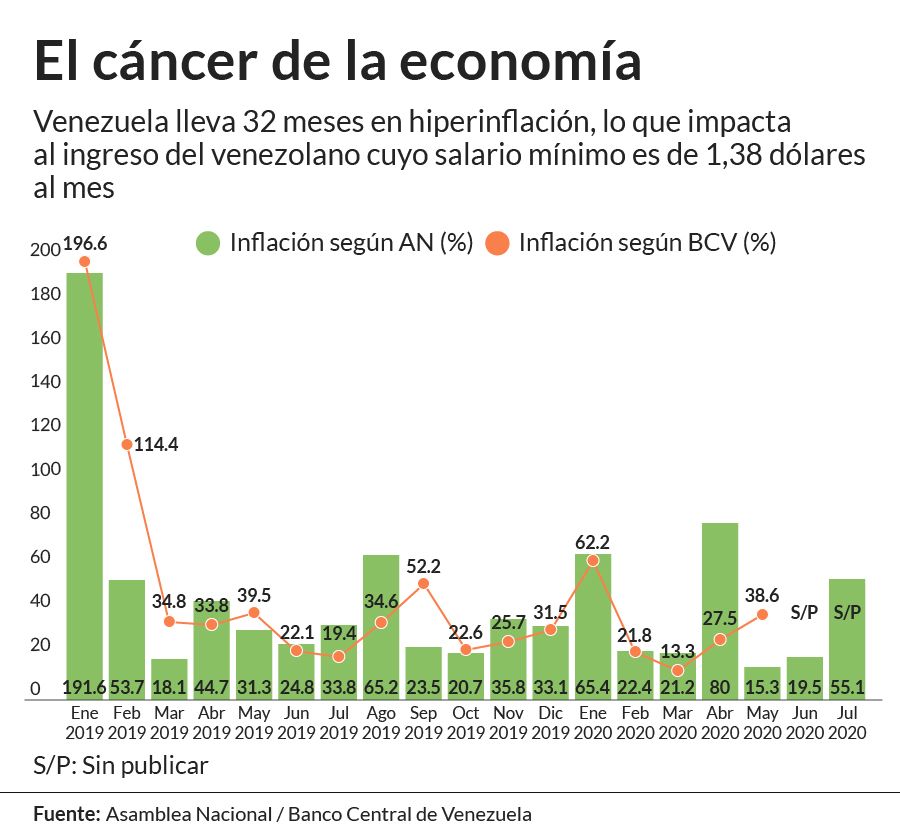

These numbers show a devastating reality: the middle class has been completely wiped out. Venezuelans are divided into a small group of rich people and a larger group who must survive on their income and subsidies on a daily, weekly or monthly basis. In the past five years, national GDP has fallen by 70% and as of March 2020, inflation has grown more than 3000%. During the same period of time, Venezuelans have seen their average incomes pulverized to less than a daily dollar. Food also became a problem. The ENCOVI survey states that only 20.7% of the people have sufficient funds to cover a market basket.

“My grandmother was also very poor and could not support me”, says Yolimar López. In 2014 she found work at an egg farm. She worked there until 2017 when Venezuela’s economy collapsed due to hyperinflation. It was during this time that she decided to leave her mother’s home in order to be “one less burden to worry about”.

Being poor is...

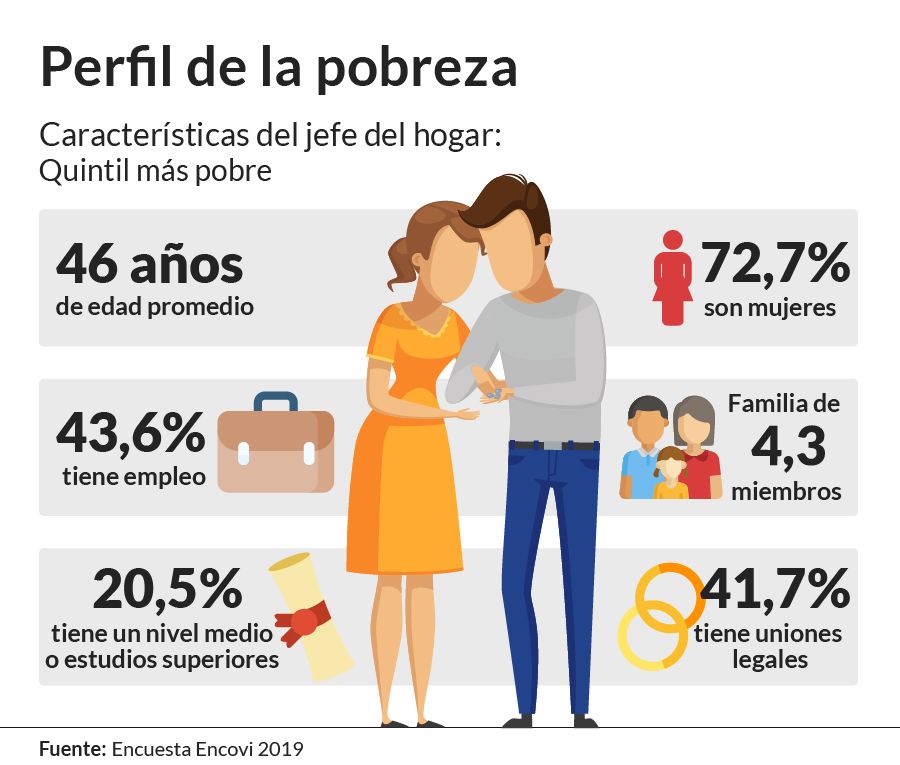

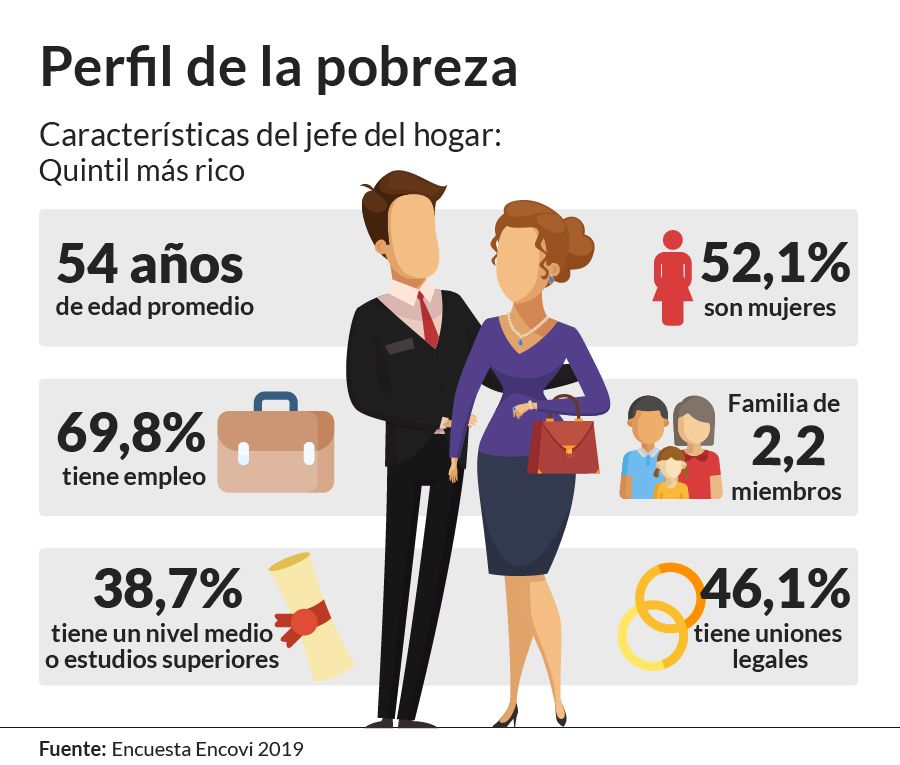

The ENCOVI survey collected data between the months of November 2019 and March 2020. Based on the information gathered, the survey was able to conclude that aside from unemployment, one of the reasons behind the general increase in poverty has been the progressive deterioration of income. A look into this data finds that women such as Yolimar López are set to take the worst beating. The survey finds that in both the poorest and richest quintiles, the head of the household is on average a woman with a median or upper low education level with an activity rate that does not surpass 60% for the highest stratum.

The survey finds that while 71% of men actively participate in the nation’s economic activity, women participation is at 43%. This means that 4 out of 10 women are involved in the Venezuela’s economic development. There is a persistence of “broad gender gaps” in every age range.

A closer look at female occupation rates by quintiles suggests that women in lower social stratums are practically unemployed. Only 29.1% of women reported to actually having a job or a stable occupation that provided them with an adequate salary. This situation widely varies with the higher stratum quintile where 58.2% admitted to being employed.

Yolimar López earns $8.00 a week for two days work at a food stand in Coche’s General Market. This is enough for her to buy “at least two kilos of rice, a piece of chicken and a piece of cheese that allows me to eat something”. The rest of the week she manages with what she has harvested in the small piece of land in a sector known as La Cortada del Guayabo, where she lives.

Yolimar’s house is made of adobe. It has no plumbing. She fills pails of water from a nearby brook which she has to carry back home. Her meals are cooked with firewood and electricity comes from improvised outlets made with telephone cables. She has no place to wash or a toilet. “For me, being poor means having to cook in a wood stove every day; not having a TV; eating white rice on a daily basis; not being able to feed my baby girl with a bib and having a house that has no access to water”, she says.

A young couple at a productive age has been forced to survive

A young couple at a productive age has been forced to survive

Héctor Rojas, Yolimar’s spouse, also admits to being poor. “We’ve always been hungry. Yesterday I had nothing to give my daughter so I dug up a cassava plant and we ate it raw. We’ve spent several days where we have nothing to eat”. He is currently unemployed. An accident left him with a wounded leg which will leave him disabled if he doesn’t tend to it soon. The couple, who has lived together for the past three years, cannot afford treatment or even go to a hospital.

Francisco Coello, sociologist and professor at the Andrés Bello Catholic University, places special emphasis on the ENCOVI survey data which groups López, Rojas and a great part of the population. “Out of the 96% of the population who is poor, more than 70% live in extreme poverty. This means that they cannot afford to eat. We are talking about an enormous problem”.

According to Professor Coello, 96% of the population “reconfigured” their position as members of society and “went to the most basic format of existence which is survival. These are people who think about how they are going to get to tomorrow, that’s how much amount of future they can afford to think about. We are talking about families who cannot afford to think about whether their children will be able to get a good job, or go to school, or gain a better socio-economic status. We are talking about people who think ‘How am I going to eat tomorrow?’ And eating a lot is a big statement. The real question is how am I going to eat something. This is the new reality in the lives of a greater part of the Venezuelan population”.

One word, two variations

Luis Pedro España, a sociologist and former director of the UCAB Institute for Economic and Social Research says that there are two types of poverty in Venezuela: income poverty and chronic poverty. The first one occurs when it is impossible to buy all of the regulatory products included in the market basket. “This usually affects professionals with a certain academic level who live in formal housing and possess certain assets and yet their income is not enough to cover their basic needs. This group of people belong to a new form of poverty which originated approximately six years ago”, explains the expert.

Out of the 96% of Venezuelans who suffer from income poverty is Evelyn Fernández, a 46 year old nurse who lives in La Dolorita, one of the neighborhoods that make up the populous borough of Petare.

Evelyn has no doubt that she fits the income poverty description. She has three children, a husband who works for hire and a salary which barely ascends to the equivalent of $3.00 every two weeks. “For some four or five years, the situation has been hard for me, especially with hospital and medical expenses (her daughter suffers from thalassemia major), public transportation and food. Everything goes into food which is becoming more and more expensive to buy”.

At La Cortada del Guayabo, making ends meet is a daily task

At La Cortada del Guayabo, making ends meet is a daily task

Finding food and a little something else puts Evelyn into consumption poverty, which affects 68% of the population according to the ENCOVI survey. “I used to be able to serve meat to my children six times a week. Now I have to make an effort to get them a balanced meal and make sure they are eating well. Sometimes I go hungry as I’d rather they eat”.

The destruction of the economic apparatus has led to the primitivization of society causing people to just barely survive, Coello attests. “Under this scenario, people have begun to manifest anxiety, depression, anguish and sleeplessness symptoms. Evidently no one at this time can claim to lead a normal lifestyle in Venezuela”.

Fernández is akin to this sentiment. For her, the situation “is rough”. The nurse claims to feel “inside a well with no exit for the time being”.

Even in Caracas, lack of public services has made living conditions seem rural

Even in Caracas, lack of public services has made living conditions seem rural

Without a proper roof

Chronic poverty in Venezuela is most commonly seen “in people who do not own a decent home or who built their home using waste materials, have a low level education and whose access to public services is either slim or almost nonexistent. The majority usually works in the informal market”, says España.

The ENCOVI survey places chronic poverty in Venezuela at 46%. Although Yakelin Márquez may not know it, she fits the data’s description. In 2013 Yakelin was a store manager at an important shopping mall in Caracas. That year former president Hugo Chávez passed away and Nicolás Maduro came into power by a narrow vote margin, marking the beginning of a major decline in all economic indicators.

Over time social classes have become undistinguishable. Society is becoming equal in poverty

Over time social classes have become undistinguishable. Society is becoming equal in poverty

This setback put many out of business and brought a new wave of unemployment. Although Yakelin had a job, her salary was dissolved by a rampant inflation which went from 20.1% in 2012 to 56.2% in 2013. That same year she abandoned her manager post and went to work at a private school in eastern Caracas.

“I was there for a year and then quit to start my own business with my husband”, says the woman who is now 47. They set up a food stand near the Oncological Hospital “Luis Razetti” in Cotiza. However the business failed due to bad sales. They decided to rent another stand, this time at El Guarataro slum, where they served fast food and beers were driven out of business in eight months due to “theft and robbery in the area”.

In 2015, Yakelin lost more than her husband. He decided to leave home but did not go empty handed, leaving with all of their home appliances. She stayed behind seven months pregnant with two other children to raise, an incoming divorce and zero income. Unable to pay the rent she went to live with her sister.

Her eldest son, still a child, wasn’t able to stay at the same house as his mother. He “lived under a bridge for four months, in a sort of outdoor refuge for needy people and troublemakers”.

Pandemic or not, many Venezuelans take to the streets on a daily basis in the quest for their survival

Pandemic or not, many Venezuelans take to the streets on a daily basis in the quest for their survival

Yakelin gave birth and returned to work as a cook, a cleaning lady and a baby sitter. Since 2017 she is an informal sales woman and is able to support all of her children under the same roof in an annex near El Junquito which she found “in exchange for the kitchen, fridge and washing machine that I managed to save from the divorce-looting”.

The house Yakelin lives in fits the description given in the ENCOVI survey of a household that lives under poverty: there is no running water, electricity, gas or other services. Yakelin completes the portrait: “I had nothing; I didn’t have anything to cook with. Just my house. So I started from there, selling whatever I could. Used clothes, shoes, tools, medicine, books or whatever I didn’t need I put a price and sold it. That’s how I got here”.

That here is the Quinta Crespo Market where Yakelin lays out a bedsheet or sometimes a piece of cardboard and sits in front of stands that have been closed during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. She is still selling her belongings, hoping to make enough to bring home a pack of corn flour or rice. “Sometimes when I have nothing to sell my neighbor gives me things and that way we both make money. On days that I make no sales or barters, we go through the market’s trash bins and always find something to take home”.

Hunger also has a place at the table

From the moment he wakes up, 34 year old public worker Rodolfo Marchán only thinks about what he will feed his wife and two young daughters for breakfast, lunch and dinner. All of these meals depend on how well he does at Ciudad Guayana’s San Felix Municipal Market in southeastern Venezuela. His jobs at the market are varied. Some days he works as a warehouse loader. On others he sells mangoes he picks from a tree in his backyard. Other times he sells bread he has baked with ingredients given to him by friends.

“Sometimes I don’t make enough money and I am forced to give my 8 and 13 year old only two meals”, he says. “In 2018, I was told not to report to work at the company, my salary was cut in half and I stopped receiving benefits. This has limited my living conditions as I don’t have the resources to feed my children three times a day”.

Marchán worked in railway operations for a State-owned company named Ferrominería Orinoco. In 2018, the company’s idle capacity was at 80% so the board of directors took the decision to deactivate his and other worker’s entry passes. He still gets a monthly salary of 300,000 Bolivars which is less than a $1.00. Until mid-August 2020 he could only buy one pack of corn flour sold at markets in the State of Bolivar for a price of Bs. 285,000.

“I survive thanks to God’s mercy”, says Marchán several times. “At least there is always a friendly hand nearby, a family member, a brother, who gives us a little something so that we can eat. We also survive thanks to the odd jobs I do in San Felix where I come from. I have to go out of my way in order to put at least one plate of food on the table for my family. Thank God I still haven’t had to beg for money on the street”.

For many, the CLAP box has become a lifesaver and sometimes the only source of food (Andrés Rodríguez | Archive El Pitazo)

For many, the CLAP box has become a lifesaver and sometimes the only source of food (Andrés Rodríguez | Archive El Pitazo)

Almost everything has disappeared from his kitchen. On August 22, 2020, he only had two sardines, one plantain, two kilos of casaba and rice in his pantry. He rarely eats chicken and meat, and when he does it’s barely once a week. In order to buy a single carton of eggs, Marchán has to work 15 days.

He has hard time admitting to it but concedes that “Chavismo has made me an economically poor worker. This government destroyed everything and made the working class even poorer. We can’t even have a bowl of soup. All of us, Chavistas and non-Chavistas, walk through Hell thanks to the anti-workers policies which destroyed our quality of life. Nicolás Maduro is an anti-worker who says he was a union leader, but it’s anyone’s guess from where”.

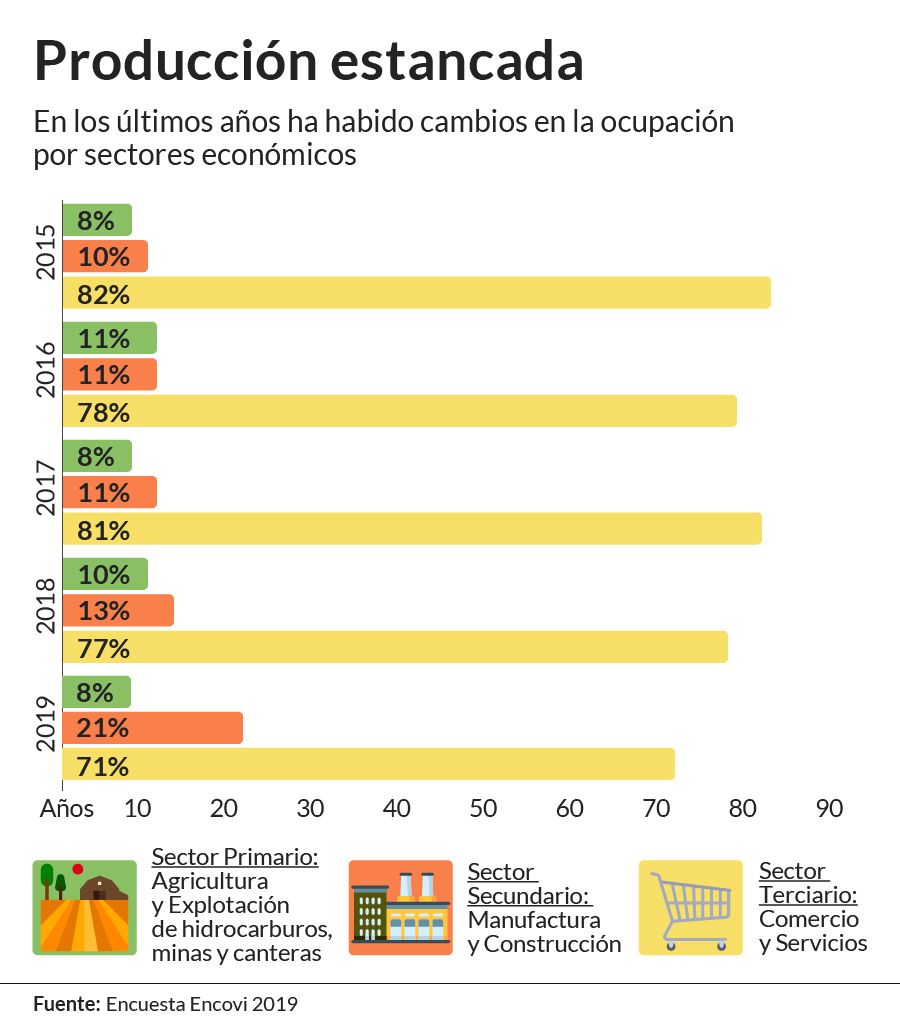

Marchán is just one of the millions of Venezuelans who have seen hunger take a seat at their dinner tables. Hunger has become undesired guest. This is a consequence of an economic model based on controls and attacks to private property called “XXI Century Socialism”. According to the National Assembly, between Nicolás Maduro’s rise to power in the second trimester of 2013 and the second trimester of 2020, 90% of the Venezuelan economy has plummeted.

Venezuelans don’t eat to feed their bodies, they eat to fill up their stomachs

Venezuelans don’t eat to feed their bodies, they eat to fill up their stomachs

This abrupt fall in the GDP generated a poverty situation for 96% of Venezuelan homes, 79% of which are living in extreme poverty. These numbers, published by the National Survey on Living Conditions (ENCOVI), portray a nation which has considerably gone astray from other South American countries and mostly resembles the situation in African countries. Only 3% of Venezuelan homes are food secure.

According to the study drafted by the Andrés Bello Catholic University (UCAB) between November 2019 and March 2020, 79.3% of Venezuelans do not have the means to meet their minimum dietary needs.

The minimum wage in Venezuela is the lowest in the world. In July 2020 it barely represented 0.54% of the basic market basket at a price of 73.97 million Bolivars. According to the Center for the Social Documentation and Analysis of the Venezuelan Federation of Teachers (Cendas-FVM), this is a far cry from May 2013 when the minimum wage was able to cover 41.2% of the basket’s cost.

The 1.6 million Bolivars Petroleum of Venezuela, S.A. (PDVSA) paid Luis Fuenmayor in the second half of the month of August 2020 were enough for a kilo of pasta, flour, half a kilo of cheese, a pack of sugar and another of coffee, two tomatoes and one onion. There was not enough available for proteins. “In order to eat we’ve had to sell the blender, the toaster, the fryer, an electric kitchen, the air conditioner and television sets”, says the 54-year-old worker with 35 years of service in the State-owned company. “We only have a small television set left. There are days when adult members in my family don’t have any breakfast. When we do is because we managed to get or sell something. Our two grandchildren are our priority”.

Fuenmayor lives in San Francisco, Zulia with his 58-year-old wife, his daughter, 32, his son, 17, and two grandchildren aged five and nine. “We used to be upper middle class. Today we are low class, one could say we are poor. Depression has hit us hard. My wife suffers from high blood pressure and has undergone a kidney operation. I also suffer from the same things but have no money to buy medicine”.

The ENCOVI survey estimates that 30% of children suffer from chronic malnutrition (Andrés Rodríguez / El Pitazo)

The ENCOVI survey estimates that 30% of children suffer from chronic malnutrition (Andrés Rodríguez / El Pitazo)

Between 1988 and 1998, Fuenmayor earned a monthly salary of $1,500 including overtime. He owned two houses and two cars. He also bought a small farm which was confiscated by military officers in 2004 during the Chávez Administration. In 2020 and with more than three decades in the oil industry, Fuenmayor makes $6.00 a week. By all international standards this is a poor man’s salary.

“My wife and I eat once a day. It’s usually pasta with ricotta and butter or green beans we find at MERCAL (a subsidized market). We’ve had to eat only rice for lunch and we must earn some kind of cash in order to mix it with eggs. Once a month we have ground beef, once a month chicken and once a month at least two or three kilos of fish. That is if we can find some cash to pay the fishermen docked at the beach at three in the morning”.

Fuenmayor claims that he is not the only oil worker who lives in precarious conditions. “But there are others lucky enough to have children abroad who are able to send them $20 to $50 a month. I was lucky this month because a friend of mine who went to live in the US saw a video where I’m at a protest rally and gave me $50 worth in Bolivars. Thanks to that my babies were able to have a good breakfast, lunch and dinner for a week while we continued our routine of having just one meal a day because we didn’t want to fool our stomachs”.

“The easiest thing to buy at the market is pasta or rice. Sometimes we cook up some sweet rice for our grandchildren. Milk is out of the question, even powdered milk for their bibs is too expensive”, Fuenmayor adds.

The 2019-2020 ENCOVI survey addresses the nutritional situation of under five-year olds. According to the survey’s weight-age index results, 21% is at risk of malnutrition and 8% is suffering from malnutrition, a level which considerably distances itself from what is registered in Colombia (3.4%), Peru (3.2%) or Chile (0.5%). Likewise, according to the size-age index, it has been estimated that 30% suffer from chronic malnutrition, which translates into approximately 639,000 children.

Marianella Herrera Cuenca is a researcher for the Center of Development Studies (Cendes) and is the director of the Bengoa Foundation. She states that the ENCOVI survey reflects a very vulnerable country with enormous gaps that must be worked on consciously and with vision, both in the short and long term. “Any attempt to overcome the gaps without thinking about the future will not be sustainable in time”.

When something’s missing on the plate

One of the few products that Nora Parra, a cook at the “Simoncito” pre-school in Fuerte Tiuna, can still buy is a half a kilo of hard cheese to fill the arepas that she, her husband and two sons will eat during an entire week. She goes to the market with every dollar she saves from mending pants to neighbors at Los Jardines del Valle in Caracas as well as the 270,000 Bolivars she earns from working at the preschool.

“You don’t live in Venezuela, you survive”, says Parra as she watches the few crops of lettuce, cucumber, potatoes and chives that she and the other cooks grew in the preschool gardens. This school is located inside the Fuerte Tiuna military complex in Caracas. “Even though it’s closed, I keep coming to pass the time. If I stay home, I’ll go crazy. It’s been tough times. I live with three men and can’t send them out to work because of coronavirus. I tell my son that we will continue to eat arepas until we can. If flour gets too expensive, I don’t know what we’re going to have for breakfast”.

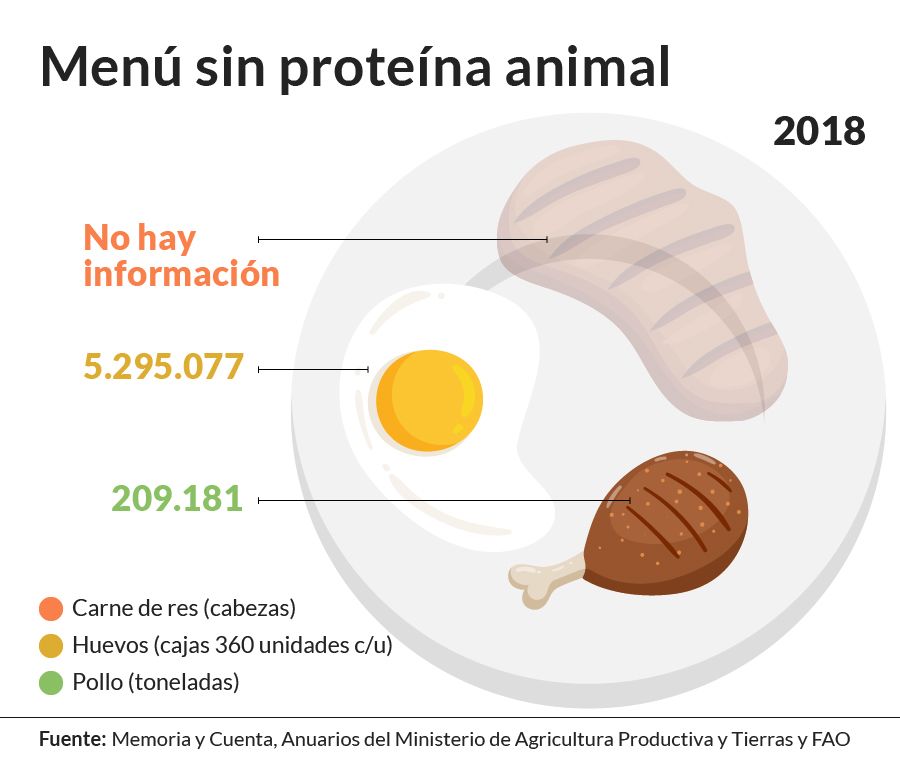

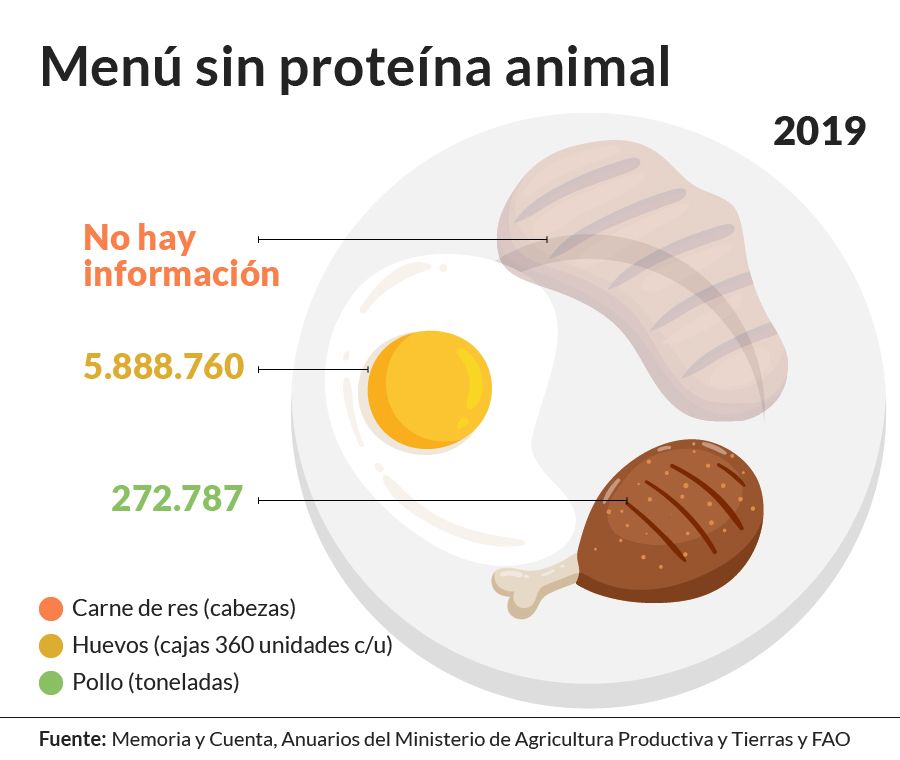

Parra cannot remember when was the last time her family ate meat or poultry but she is certain that it was way before the pandemic. On the space where she used to place the animal protein, Parra now serves green beans and lentils. She earns a monthly salary of Bs. 540,000 at the “Simoncito” preschool. By mid-August 2020, meat was valued at a million Bolivars and a kilo of chicken was worth Bs. 600,000 in all of the municipal markets in Caracas.

“Prices on the street are crazy. We practically depend on what we get in the CLAP box. We eat rice with grains and sometimes I sauté tomatoes and onions and chop a little bit of mortadella to make a sauce for the rice”.

Nutrition of low-income Venezuelan families is almost entirely composed of carbohydrates. By mid-August 2020, the combined price of meat, poultry and eggs was approximately Bs. 2.61 million. Therefore, the average consumption of proteins barely reaches 34.3% of what is required, the ENCOVI survey reports.

“Something is always missing on my plate”, says 33-year old Franklin, a man who lives in Charallave, Miranda State. “I eat a full plate two or three times a week but there are days in which something’s missing. There are days where we only eat grains in order to stretch out our meat supply. We also can’t eat salads because the price of vegetables is too expensive. So one day we have meat, the next only vegetables, the next chicken, then rice with grains and a salad. We vary the menu in order to stretch out our groceries for two weeks”.

An entire generation grows without an adequate diet that can guarantee their development (Andrés Rodríguez / El Pitazo)

An entire generation grows without an adequate diet that can guarantee their development (Andrés Rodríguez / El Pitazo)

According to a study by the World Food Programme executed between July and September 2019, 9.3 million Venezuelans are either moderately or severely food insecure. 60% of the population has had to cut back on the portions they eat. The consumption of meat, fish, eggs, vegetables and fruits is under three days a week.

“We’ve been through tough times. Most of all I’m worried about salty foods (proteins) because I don’t have the same income I had before the pandemic and prices go up every day”, says Franklin. He is a self-employed construction worker who has two other jobs, one as a janitor at Fuerte Tiuna and another as a taxi driver for a company in Charallave where he lives with his wife, a 5-year-old boy and a baby born in February 2020.

“Some jobs pay me with food”, says Franklin. This is not unusual. The UN study says that 33% of Venezuelans agree to work in exchange for food products. “Because I’m a worker at Fuerte Tiuna, I also am eligible for a CLAP box. But the box rarely arrives on time in the community where I live. It used to arrive once a month but now it’s every two months. And when we do get it, it always seems to come with less products. This is pretty hard. The box no longer contains milk, sugar, sauces (mayonnaise and ketchup), tuna or lentils. A lot of my neighbors depend on the CLAP box much more than I do. They’ve had a very, very, very bad time”.

According to the ENCOVI survey, CLAP boxes and bonds are the only food program the government has for families. They all basically contain rice, grains and pasta. Approximately 5% of those in extreme poverty do not receive this food subsidy and 15% receives it every two months.

According to the NGO Ciudadanía en Acción, in July 2020 the CLAP box weighed 7.8 kilograms, which is a decrease of 11.2 kilos when compared to the 19 kilograms it weighed in 2016, when Nicolás Maduro’s food program was born. At the time, it reached 41% of 6.15 million households who had registered in the government webpage. On average, the box takes 41 days to arrive.

“The bad news for Venezuelan families is that the only emergency supply available to poor families is disappearing. This has led to an increase in food scarcity and increased or sustained levels of chronic malnutrition”, says Edison Arciniega, Executive Director of the NGO Ciudadanía en Acción who specializes in development and food security.

According to the ENCOVI survey, the average national consumption of protein is only 34.3% of what is required (Andrés Rodríguez / Archive El Pitazo)

According to the ENCOVI survey, the average national consumption of protein is only 34.3% of what is required (Andrés Rodríguez / Archive El Pitazo)

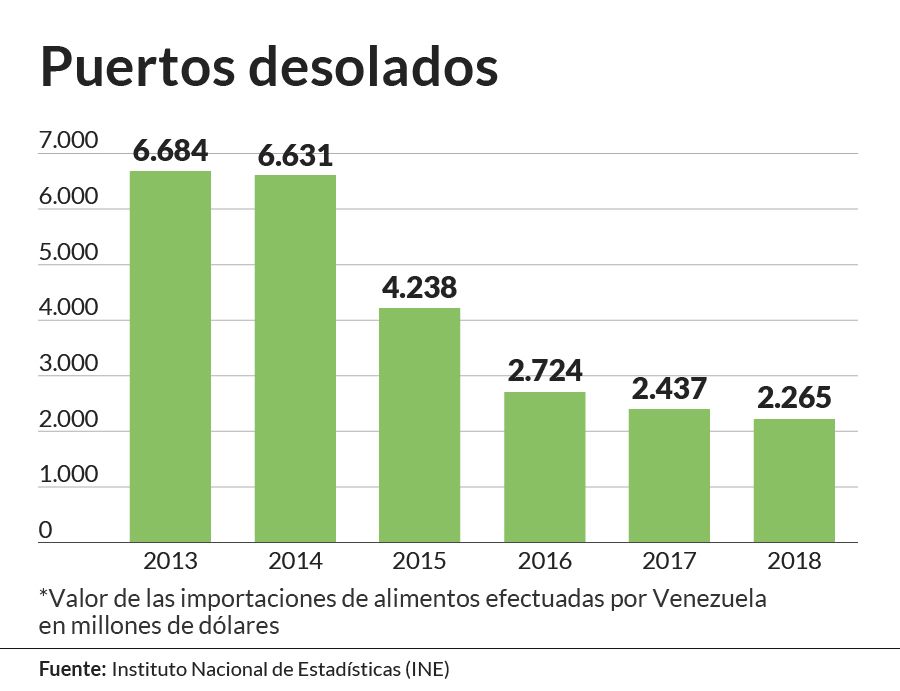

An incapable State

The Venezuelan State is finding it increasingly difficult to import food. The collapse of the oil industry, which provides $86 of every $100 that flow into the country is the main reason behind this decline in revenues. A drop in oil prices, trade barriers imposed by US sanctions, PDVSA discounts and the current effects of COVID-19 have also contributed to the lack of funds.

The national productive sector does not have the capacity to meet the supply that the decrease in food imports has caused. Every sector of the national production is living its worst time in Venezuelan history.

Between 2002 and 2019, the national production of meat went from 565.000 to 169,000 metric tons, a collapse of 70% according to Carlos Albornoz, president of the Venezuelan Institute of Milk and Meat Products (Invelecar). “The Law of Lands and personal, legal and economic insecurity caused a great breach in the productive rural economic sector. In 2002, the yearly consumption per capita was very close to 20 kilos. In 2019, it barely represented four kilos a year”, says Albornoz.

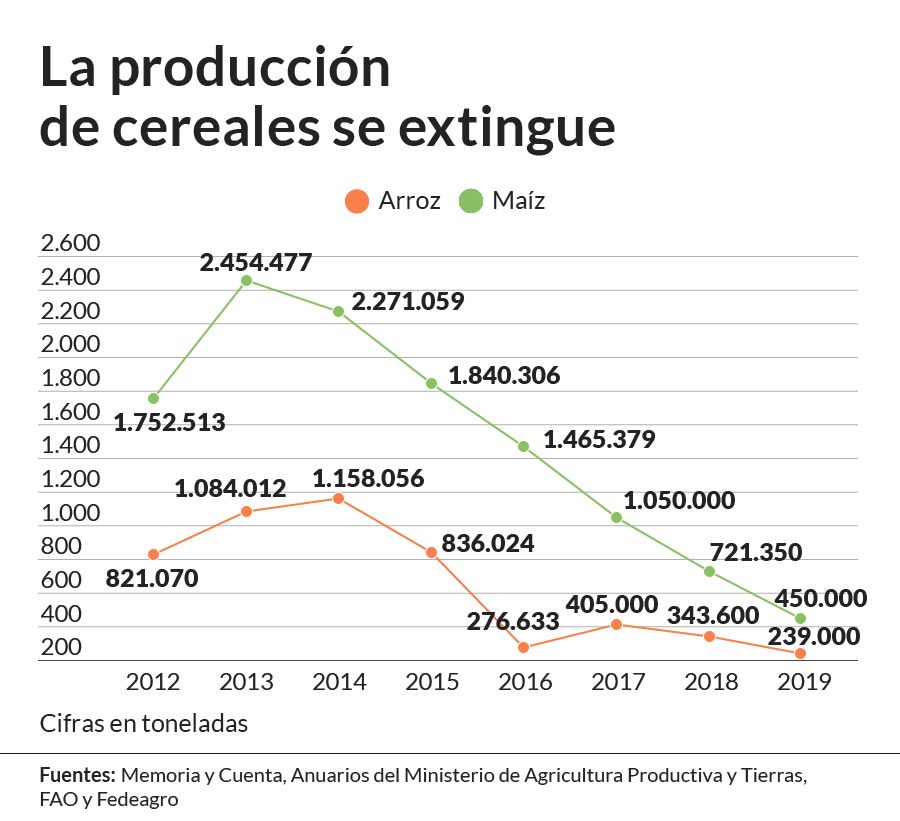

Problems in agriculture have also played a key role. Since 2008, production has dropped in more than 70%. The reasons behind this are interventions to agricultural property through land confiscations, illegal invasions and expropriations, price controls, growth of agricultural imports without tariffs customs and set at a preferential dollar rate which competed disloyally with what was grown in Venezuela. Other reasons are the limited resources the bank industry had to grant credits, rural insecurity, technological setbacks, obsolete machinery and equipment and the severe scarcity of seeds, fertilizers, chemicals, exchange parts, lubricants, gasoline, tires and other materials.

Shortage of gasoline which does not seem to have a solution in the short and long term as well as the coronavirus pandemic are new additions to the problems that farmers had since the sustained drop began in 2008.

It is expected that the 2020 harvest will be inferior to what was harvested in the 1960’s and 70’s when the population did not surpass 15 million inhabitants. Corn, sorghum and rice production is disappearing. The 2020 projection is that production will be half of what was harvested in 2019, which was barely enough to feed 1 out every 10 Venezuelans.

“Everybody sells something to survive”

“The crisis has hit us hard. I have my own lawn mower but nowadays I can’t find as much work. I pray to God that I find a job somewhere, painting, plumbing, any kind of small work”, says Ángel Bello, a 31-year-old gardener who lives in the neighborhood of Petare in Caracas. He is the father of three children aged 10, 5 and 3. His wife is currently eight months pregnant with a baby girl.

Ángel is illiterate. This has prevented him from making ends meet at the end of the month. He is a part of the Venezuelan population that makes up the informal work sector. All of them are seeking any type of job by the hour that will enable some sort of income.

“I’ve never worked for a company or had a real job. I freelance with gardening and pruning trees. It’s hard finding work at a company when one doesn’t know how to read or write”, he says.

For decades, casual work has occupied a significant quota in Venezuela’s labor market. The economic policies of the last 20 years have generated a complex crisis which has led to the impoverishment of a population whose income has evaporated. In order to survive and “get ahead”, many people incur in what is popularly known as “matar tigres” (killing tigers), an expression for finding odd jobs.

“Matar tigres” or finding odd jobs has gained ground as the main source of income in Venezuela

“Matar tigres” or finding odd jobs has gained ground as the main source of income in Venezuela

“Right now I am in a tight spot because my wife is about to go into labor”, says Ángel worriedly. Sporadic jobs, which require only a few hours three to four times a week have been hard to find. “I always found something, maybe mowing a lawn or pruning some bushes. These days it’s hard to find someone who requires my services. I began charging in dollars but can’t seem to land any work. There are days where I walk around the area where I usually work in without doing anything”.

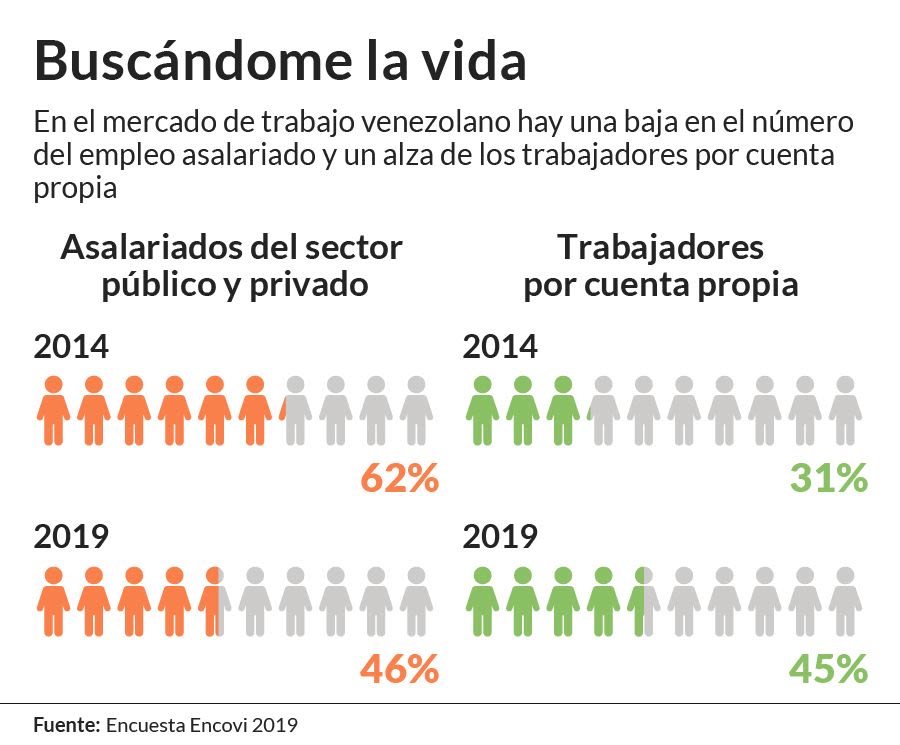

The unemployment rate in Venezuela has varied through the years. The 2019-2020 ENCOVI survey reveals that the level of economic participation of the population (ages 15 to 60) in Venezuela is around 56%, the lowest in Latin America. The greater percentage of unemployment is precisely in the lower income sectors (quintiles 1 and 2) with a rate of 57% and 52%, respectively.

Evolution of participation in the country’s economic activity in the last five years shows mild descending fluctuations at around the same level reached in 2015 (…) The ENCOVI study reveals that the rate is closest to Argentina (58%) and farthest from Peru (72%).

44% of the unemployed population claims to tend to household responsibilities. In fact, women represent 43% of the economically active population while 71% are men. This is an indication of the small participation Venezuelan women have in the workforce. The greatest gap between the number of male and female workers is observed in the 55-64 age rank.

The ENCOVI survey indicates that reasons such as the “contraction of the labor market, a predominantly male emigration and work from home transfer systems may have given women a lesser participation in the workforce and cause them to take refuge in unemployment (…) Employment rates are an evidence of a broad gender gap in all ages”.

Ángel’s wife does not work. At 23 years of age, she must prepare to tend to her three children and make way for the new member of the family. She and Ángel hope that the baby can be delivered at El Llanito Hospital, located in the Municipality of Sucre in Caracas.

“Some of my clients are good natured people and I’ve talked to them about helping out with my wife’s delivery. Some have said that they can help with diapers, towels, a bathrobe for my wife, and other things; but not with money because no one has cash these days. I am grateful that they are helping us because tests are expensive. An ultrasound costs around $11 and a SMAC 20 blood test around $6. “I don’t have that kind of money”.

Low purchase value has turned Venezuelan bills into an eccentricity (Photo: Ronald Peña / Archive El Pitazo)

Low purchase value has turned Venezuelan bills into an eccentricity (Photo: Ronald Peña / Archive El Pitazo)

Through the years the young gardener has also seen how Venezuela’s economy has deteriorated, affecting him significantly. Years before, he says, his income allowed him to buy his two eldest children food, clothing as well as pay for any medical tests and vaccines. His third child, a three-year-old girl, has not been able to get vaccinated because Ángel can’t afford it.

The ENCOVI survey says that 96% of Venezuelans are poor because their income prevents them from covering basic needs such as food, health, services and recreation, among others.

According to the World Bank, extreme poverty occurs when people live on $1.90 a day or less. In Venezuela, the minimum wage is $1.38 a month. In September 2020 this translated into $0.045. In addition to this, Venezuela has spent 32 months of hyperinflation. The country’s accumulated inflation since March 2013 until May 2020 was 12,323,312,864%, a difficult number to pronounce and digest

Born and raised in Petare, Ángel is reminiscent of better times. “In those days, I could use what I earned to buy food at Makro (a wholesale supermarket) and buy diapers, flour and rice by the bulk. That is impossible today. We got our CLAP box a few days ago and it came almost empty. No sugar, no oil and only one pack of flour. The spaghetti bag had opened and they were strewn all over the box. It was as if they dreaded giving us the box. The situation grew complicated ever since (Hugo) Chávez died and (Nicolás) Maduro came into power. They don’t want to help the poor, they want to starve the poor to death”.

Ángel Bello is a gardener but takes any job he gets in order to bring food back home (Ahiana Figueroa)

Ángel Bello is a gardener but takes any job he gets in order to bring food back home (Ahiana Figueroa)

For the majority of the population “whatever they earn today must be spent immediately”, especially if their earnings are in Bolivars. It seems that everyone is aware that Venezuela is in its third consecutive year of an historic hyperinflationary process and a devaluation of the currency rate which does not seem to end.

“Whoever receives Bolivars in Venezuela must know that he is getting waste and only takes it because he knows that it can be charged onto somebody else. This is well known by those who every two or three weeks receive transfers or bonds that the government grants as part of the social programs enacted to reduce the effects of the crisis”, says Leonardo Vera, an economist and professor at the Institute of Higher Administration Studies (IESA).

Ángel talks about how much the local currency is worth. “A Bolívar is worth nothing and dollars are scarce because dollars are not printed here. If those who are in the government right now keep taking the few dollars that are here, we are all going to die of hunger. The other day Maduro said on national television that every Venezuelan has a right to have Bs. 200,000 in his pocket (he is referring to the payment of a bond). Those 200,000 are not even enough for a pack of rice or flour”.

In the meantime, Ángel feels that he and his family “have not had any luck”. He takes refuge in God and hopes his current situation will be better in the future so that he can continue to work on what his father taught him: gardening.

“We’re going to a church called The Voices of God and we’ve done better. At night we pray and ask God to help us. A lot of people have lost hope but I always tell them to not despair”.

Freelance Jobs

The struggles Venezuelans go through in order to make money has been so great that there has been a widespread increase of freelance workers. This has included professional workers and people with postgraduate studies. The ENCOVI survey suggests that there has been a diminishment in salaried employees which went from 62% in 2014 to 46% in 2019. The survey also reveals that in those same years ethe total number of freelance workers went from 31% to 45%.

“Although I am an experienced teacher and continue working, around 2018 I began to take interest in the business of beauty. So I took manicure, pedicure, and waxing, courses and began offering at home services”, says Natacha Paredes, a Plastic Arts professor who has been working for 14 years in the Ministry of Education.

Natacha is 36. She is married to another professor and is a graduate from the Pedagogical Institute of Caracas. It was in 2017 when she began to notice how her income had stopped covering her expenses. She blames inflation and the suspension of her collective agreement for the complete wipe out of her salary at the Ministry. Today she makes do with her extra income. “There are many times when what I charge for a day’s worth of services at the beauty parlor is equal to what the Ministry pays me for two weeks of work at a Bolivarian school”.

Going to work at a private school is not a guarantee of a better salary, says Natacha. “I have colleagues who quit public school and went to work at private schools, where they offered them a good salary plus a bonus paid in dollars. Some never got paid that bonus and others never saw a raise except for inflation”.

She says rather disappointedly that although she has a Master’s degree, her salary was never enough to what a person with her academic status should be paid. In fact, her husband who also took postgraduate studies, decided to quit teaching and began work as a systems programmer and computer repairman. “You complete higher studies thinking that you’re going to get a better salary but it turns out to be otherwise”.

Natacha Paredes still works as a teacher “because I love doing it” but makes her money somewhere else

Natacha Paredes still works as a teacher “because I love doing it” but makes her money somewhere else

Public employees are paid much lower salaries than the rest. Froilán Barrios, a member of the Worker’s Movement (Movimiento Laborista) says that public sector workers, employees, professionals, and university professors “are the most impoverished” since their monthly salary goes between $1.30 to $20.00.

Barrios says: “If we look at the economy’s private sector which registers an approximate of three million workers, we can see how this sector has maintained collective agreements even when we all know that its syndicate rate is a third part of what the public sector has”.

He says that wages have been more dynamic in the private sector because the private employer pays more than the minimum wage and also has begun to pay bonuses in dollars. “Nowadays you can find a security guard at a shopping mall who is earning the same amount as a public university professor”, says Barrios.

Evidence of the minimum wage’s deterioration in Venezuela can be found when comparing earlier figures. For example, in May 2019 the minimum wage was set at Bs. 40,000 which at the time was the equivalent of $7.70. Meanwhile, in September 2020, a minimum wage of Bs. 400,000 represented less than $1.00.

The ENCOVI survey indicates that the among the benefits employees or workers receive, 96% of workers in the private sector receive a salary, 55% receive a meal voucher, 11% commissions and tips, 9% overtime, 5% transportation bonus, another 5% receive a productivity bonus, 3% income in Petros, 2% seniority bonus and 1% are granted child benefits.

On the contrary, 97% of employees in the public sector receive a salary, 70% receive a meal voucher, 36% income in Petros, 7% a seniority bonus, 5% are granted child benefits, 4% overtime, another 4% have transportation, 2% receive commissions and tips and another 2% get a productivity bonus.

“Two, three or four dollars do not generate enough income for survival. In the end, two minimum wages do not allow a person to earn enough for the basic consumption basket and medicines. A family requires $100 to $200 a month to cover their needs”, says José Manuel Puente, an economist and IESA professor.

In just five years, employment in the manufacturing industry was cut in half

El sector manufacturero redujo a la mitad su capacidad de absorber a la fuerza de trabajo solamente en cinco años

“One of the main problems in Venezuela is that over half of the population works freelance or is involved in casual work. If we add all of the workers who earn a minimum wage, it gets you closer to a percentage of the population who needs to go out and search for other sources of income”, Puente says.

For Natacha, having extra sources of income through her hair dressing services has allowed her to fix up her house and to save some money. She recently took her mother to a local clinic and was able to pay for medical services, tests and medicines. This young teacher also has an important goal which is worth the effort of having two jobs: have babies and raise a family”.

“My husband and I are undergoing fertility treatment because we haven’t been able to have any children. Our extra income has helped us cover the medical bills which as we all know this kind of procedure and the tests required are not cheap and are not covered by insurance. This is what all that income has been used for.

A personal decision

It used to be that unemployment in the formal sector was a direct cause of less income and an increase in taxes which prevented businesses from maintaining a certain number of employees in their companies. In the last few years, the decision to work as a freelancer or an entrepreneur has become a personal decision. “This is motivated by different factors such as need and opportunity”, says Asdrúbal Oliveros, an economist and director of Ecoanalítica consulting group.

This is the story of Jaime Rodriguez, a 43-year-old attorney who graduated from Central University of Venezuela (UCV) in 2003, where he also took postgraduate studies. After several years of working in the public sector he began practicing law on his own until he decided to open a food delivery business.

Seeking a decent income, Jaime Rodríguez went from being an attorney to an entrepreneur

Seeking a decent income, Jaime Rodríguez went from being an attorney to an entrepreneur

“When I began working, my salary was enough to buy myself a car, move out of my parents’ house and become independent. In 2010, the situation began to worsen and by 2014, salaries were good for nothing. Besides, legal practice became difficult because of costs related to services provided by registries and notaries. I couldn’t get anything done if I didn’t carry a sack full of cash under my arm. That’s when I decided to become an entrepreneur”, he says.

Jaime began by selling poultry. “I began the business practically by myself. I would clean, pack, prepare and deliver the orders. After my cleaning lady quit because I wasn’t able to pay her, she began working with me in the business. A man who worked as a driver for a family that moved out of the country also came to work for us and he now helps me with the deliveries. What began as an incentive to make ends meet turned into my modus vivendi”.

According to the ENCOVI survey, the most popular sector among the active population to find some sort of employment is trade and services. “More than 80% works in this area”, says the study.

Jaime says that only a handful of his colleagues and/or attorney friends are still involved in legal practice. Many opted to work on their own or start a freelance business. “In the spirit of survival, Venezuelans have looked for one thousand and one ways to keep going. Everybody is selling something”.

Six years later, Jaime’s business line has expanded to include groceries and cleaning products. “My business has changed because nowadays my main customers live abroad and need to help the family they left behind in Venezuela, especially their parents and grandparents”.

Schools: A Missing Step in the Social Ladder

Ángel Cabello was a freshman in high school when he turned 16. He was also on his second try to pass. Money was tight at home at the neighborhood known as El Plan de la Cota 905 and his mother was a single parent trying to make ends meet with three children to raise. Ángel began skipping class once or twice a week. Then he started missing an entire week until one day, without almost noticing, he stopped going altogether. Gone were the days of hanging out with his friends at the basketball court. His name was jotted down under the “failed for unattendance” box.

“I have to work”, he said to himself.

He had already stripped out of his blue school uniform to work as an electrician’s assistant. His mother did not like that this son quit school and insisted he take night courses so that at least he could get his high school diploma. So Ángel gained a second wind and enrolled once again. It was 2017, an annus horribilis for the Venezuelan economy. Hyperinflation had become a phenomenon of scandalous numbers. Breakfast began to disappear from Ángel’s family table. Meals were cut into half.

Classrooms have been getting emptier (Andrés Rodríguez / El Pitazo)

Classrooms have been getting emptier (Andrés Rodríguez / El Pitazo)

“Sometimes we would not have anything for breakfast and I would go straight to work. My classes were in the evening so I used the time to make more money. But I began skipping classes and quit school again”. This time his mother said nothing. She is someone who knows about dropping out because she too went through the same process. As a young woman, she was forced to abandon her studies and work to raise her children. Even so, she never gave up until she finally graduated as an accountant at age 40.

Ángel tells this story proudly. A shy smile comes across his face when he thinks that his mother’s story may be well be his own. “I’m now 19. If I can get through high school in two or three years I can go to university or take a short course and graduate by the time I’m 25”.

His main obstacle, however, is a term he has been hearing everywhere for a long time: situación país, a term Venezuelans often use to describe the current state of the country. He does not know how to explain the concept very well, but clearly understands that it is a combination of issues that do not play in his favor.

Ángel Cabello dropped out of school but enrolled again in hopes of completing his studies

Ángel Cabello dropped out of school but enrolled again in hopes of completing his studies

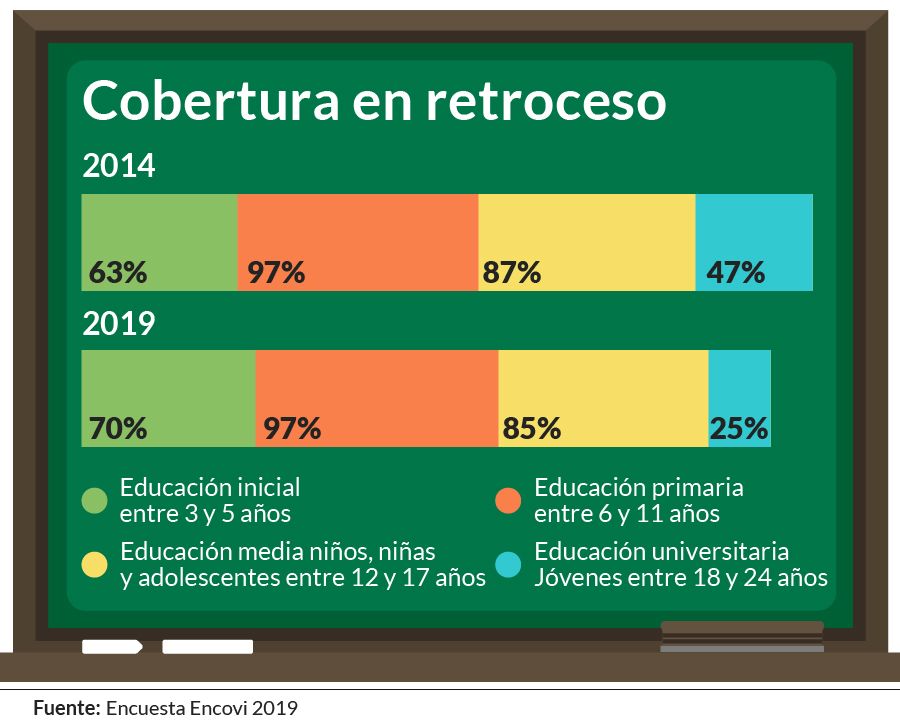

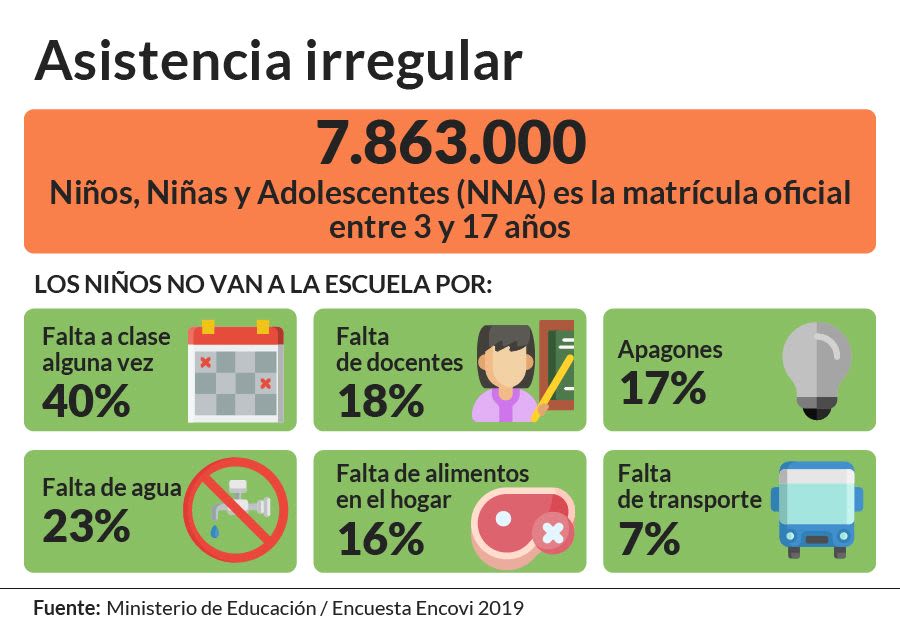

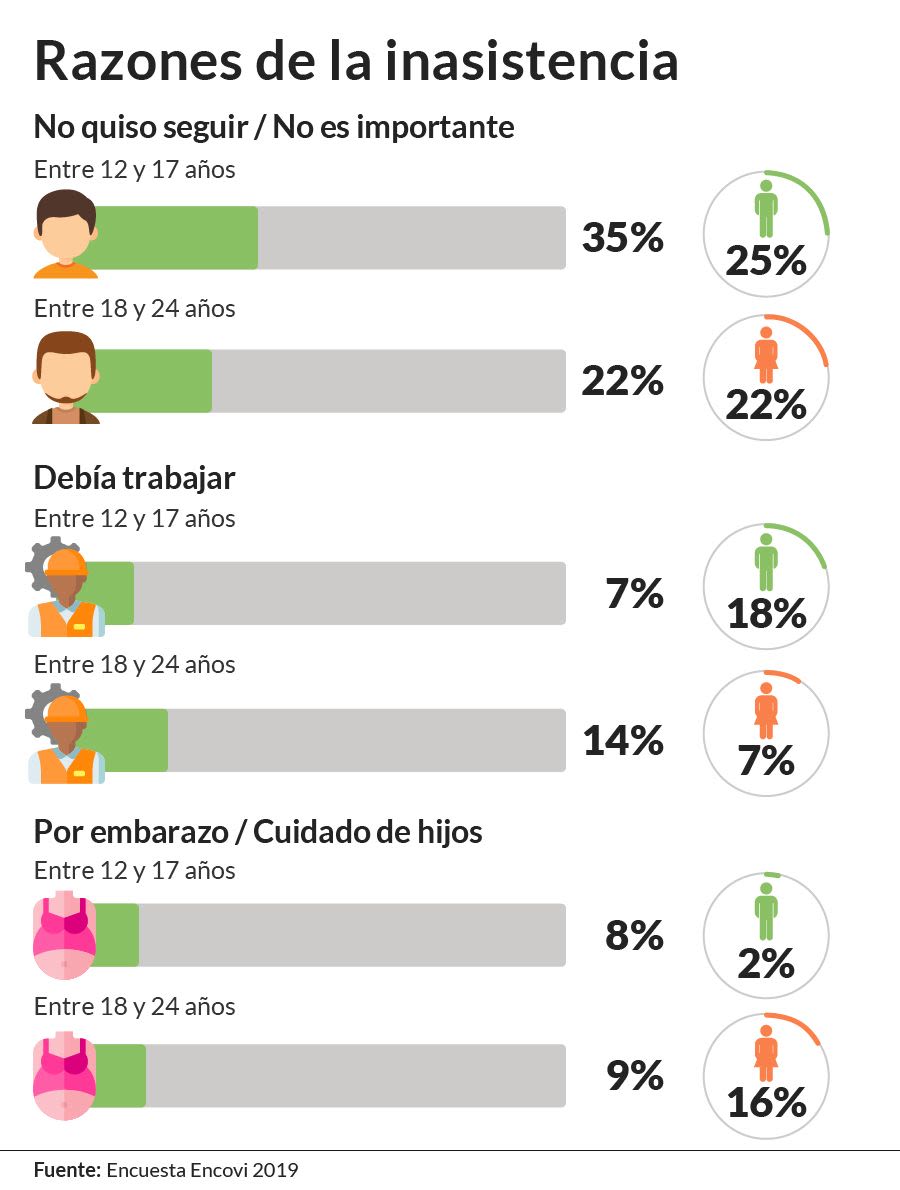

This “situation” is just a long list of indicators that reveal the setbacks of the Venezuelan school system in the last five years. According to the 2019-2020 National Survey of Living Conditions (ENCOVI), the setback is most alarming in children and teenagers aged 12-17 who come from low income sectors. Three fourths of the population between 18-24 years of age abandon high school, the survey says.

At 19, Ángel’s main task is making enough money to buy food for lunch at home. He lives with two brothers and two nephews. Nobody has to tell him that he is in charge. Ever since he can remember, his mother has left home early for work.

The ENCOVI survey adds numbers to a marker known as social exclusion. While 44% of people aged 18-24 who come from a low-income stratus are able to attend school at the adequate age, barely 16% of those who come from low-income families are able to complete their studies.

While she helps her sister in law with a small convenience store located in the living room of a narrow house at La Cota 905, Nelsimar Prin speaks about her passion for forensic science. She has just turned 18. Last year, while getting her High School diploma, she held her new born child in her arms. She and another classmate were both pregnant during their last days of school. It was hard work but she got through it thanks to the support of her mother.

This young woman became an adult with a baby to take care of. As a woman, her risk of abandoning school because of pregnancy issues is eight times higher than that of the father of her child. This is what is known as a gender gap and which the ENCOVI survey compares with other young women of her same age. 16% of women abandon their education when they become a parent. Only 2% of men do the same.

During the days of strict confinement due to the enforced quarantine caused by COVID-19, Nelsimar tends to her baby. However, she cannot stop thinking that her life plans have been delayed indefinitely for another reason: right now, she cannot commit herself to a full online semester. “As soon as I can, I’m going to be the first member of my family who attends university”.

Nelsimar’s academic path is being threatened by family and budgetary issues

Nelsimar’s academic path is being threatened by family and budgetary issues

Nelsimar studied at a public school. It was close to home which meant that she could save up on transportation. “Many of my classmates had a hard time getting to school and ended up quitting”. When it wasn’t the bus fare, it was lack of food or water, or shoes or school supplies. She was lucky. “My mother did everything she could for me to have everything I needed”.

But the financial responsibility of having to raise a daughter has meant postponing her goals. Ever since quarantine began, neither she or the father of her child are employed. Their entire income depends on the sales of the convenience store which they must share with their mother and sister in law, who also has two children.

“Getting an education is not enough, we have to make money. I know people who have gone to school and are professionals but they don’t make money. The country’s situation doesn’t help either because everything you earn goes into buying food”, she reflects.

According to the ENCOVI survey, more than a third of the population who are fit to attend school have dropped out. The second reason to do so is “not wanting” to continue or “not deeming it important”. After all, between the poorest quintile and the richest quintile in the country, the difference of education level is 1.8 years. The current poverty status in Venezuela does not respond to education levels. More time sitting behind a classroom desk does not necessarily distance you from poverty.

Nelsimar stares at the floor for minutes at a time as her daughter crawls and rehearses her first steps. They are both at home. Nelsimar gets up from the floor, fixes her daughter’s ponytail and says out loud: “Studying is like a chain. You want to be better at what you do and have dreams. My mother helped me and I hope to help my children”.

Anthony Chacón, 16, doesn’t say much. All of his answers are short. “Yes. No. I hadn’t thought about that”. When asked why he left high school two years ago just as he was about to enter his third year, he is evasive. The only time he looks away from the motorbike he is repairing is to wipe his hands with a rag and reply to a text message on his phone.

-I dropped out of school because I needed money.

-But did you like going to school?

-Not much. I wasn’t very good.

-What did your mom say when you dropped out?

-Nothing. She knows why.

Anthony repairs motorcycles in an area close to his home in El Valle where he lives with his mother, a 20-year-old brother who is also in the motor repair business, a 23-year-old-sister, a younger brother and three nephews.

“To tell you the truth, studying is not my thing”, he says firmly. In his opinion, there is no point in studying when one has to find a way to make money to pay the bills at home. “I don’t think it’s better or worse for anybody”.

His mother Lismary looks out the door to where her son is working. Also brief with words, she explains that she would have wanted all of her children to get an education primarily because she wasn’t able to complete her own studies. She became a mother in her teens and has created a life of her own ever since. “It’s always been up to me for everything, but in the past few years things have gotten worse and I can’t manage on my own. My kids may not have gone to school but none of them can say they went to bed hungry”. Lismary also supports her eldest daughter who recently separated from her husband and came back home with three children between the ages of two and five.

Four adults and four children live together at Lismary’s home. The only one who is still in the school system is Anthony’s 12-year-old brother who has just completed the sixth grade.

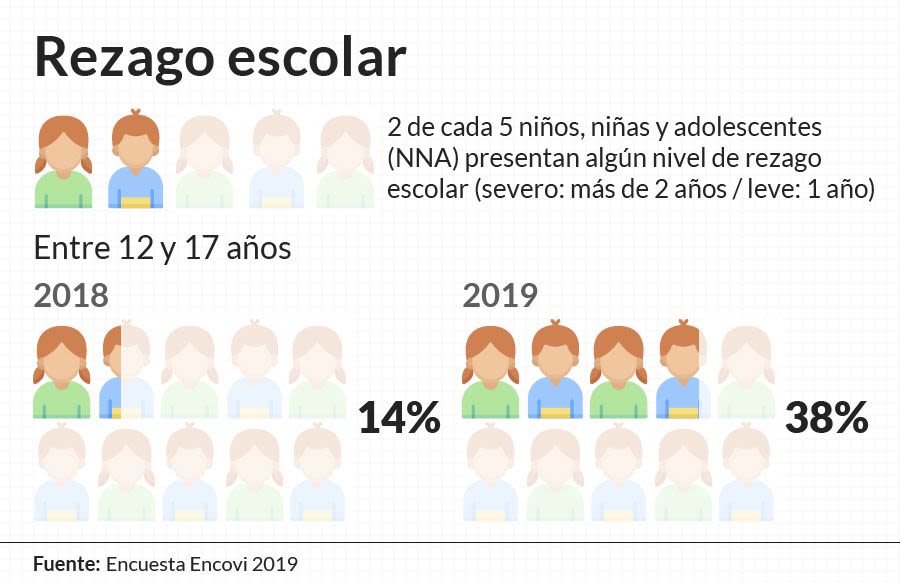

Dropping out of school is usually preceded by an educational lag. This refers to those who remain two or more years behind their corresponding academic level. According to data, since 2014 this has been most predominant in the 12-17 age group. The ENCOVI survey shows a wide gap between the poorest social stratus and the richest: 27% of those who have less resources are under a severe educational lag at school.

However, both extremes offer unpromising data, especially when compared to the preceding school year (2018-2019). Classroom teachers found that two out of every five boys and girls had some level of educational lag of at least one year.

Where are the young people?

Three years of setback is all it took for Venezuela’s educational coverage to be cut by half. Data from the 2016 ENCOVI survey revealed that 48% of the population received an education. By the end of 2019, the population barely reached 25%

These are the same three years that Ángel has not set foot in a classroom. A panoramic view of Caracas can be seen from the corner of the house he lives in with his family at Cota 905 Road. He places his foot on the border of a path that marks the boundary towards a precipice of waste where a cascade of trash falls onto the main avenue.

3.14 million Venezuelans make up the 18-24 group which incidentally has the worst living conditions in the nation. Ángel is included in that group. According to the 2019 ENCOVI survey, 2.82 million of them do not go to school.

But if they are not at school, or university or working, where are they? Lack of public information does not help matters. The Ministry of Education has not released official numbers in its Annual Report since 2015. In 2017 they ended the practice of publishing opening and closing day attendance numbers.

TalCual gained access to a document published by the Ministry of Education’s Admissions and Registration Department which shows the student population for the 2019-2020 school year. The document reveals a general, albeit not so drastic, decline. In the 18-24 population, 1,575,201 million students are enrolled in secondary school while 55,000 are enrolled in technical secondary school.

The school’s open doors are also a way to get out and never come back (Andrés Rodríguez / El Pitazo)

The school’s open doors are also a way to get out and never come back (Andrés Rodríguez / El Pitazo)

Tulio Ramírez, a sociologist and researcher on education, agrees that Venezuelan migration has played a role in the decline of student enrolment because entire families with children at an academic age have left the country. However, it is also noteworthy that the tradition and culture of school in low-income families also has an important weight.

“It is true that public high schools offer plenty of disincentives, but families, especially low-income families, have kept the tradition of sending their children to school, making every effort they can to keep them in the school system. Upward mobility has very little do with this. Parents would rather send their children to school to keep them busy than having them at home doing nothing or, worse, in the streets”, says Ramírez.

Ángel’s seriousness contrasts with the teenager face he still keeps at 19. He silently watches everyone who walks by him on the path, never turning his back away completely. But he also can’t stop gazing at the enormous city that opens panoramically in his eyes.

From La Cota 905, the future has been severing ties with academic achievement

From La Cota 905, the future has been severing ties with academic achievement

“I still feel that I can make it”, he answers to a question no one asked him.

-You mean getting your High School diploma, going off to university?

-Yes. I think going to school or not depends on oneself. Family also plays a part, whether they support you or if you feel like it. Of course, the state of this country makes everything difficult. I feel I missed out on opportunities because I didn’t have my father around. My mother is all I got. But I also know plenty of people whose parents pay for their education and don’t even try because they want everything served on a platter.

-And where do you see yourself in the next five years?

-I want to study Electric Engineering, because I’m good at that and have learned a lot. I also thought about studying Tourism because I love getting to know other places and cooking. I see myself with my own fast-food restaurant, inventing my style and learning how to use ingredients”.

A long and complicated road ahead (Andrés Rodríguez / El Pitazo)

A long and complicated road ahead (Andrés Rodríguez / El Pitazo)

For now, all of his plans are “in the future” which is a phrase that appears often in his conversation. The lack of activity caused by the quarantine has been a new obstacle to sort out because work has been reduced to its core and he can barely find something to do. But want knows nothing about confinement and his mind is kept busy by figuring out a way to help his working mother keep their home afloat.

-You really want to know what I want the most? I want to have another kind of life and someday buy my mom her own house”.

"For me, being poor means having to cook in a wood stove every day"

"I used to be able to serve meat to my children six times a week. Sometimes I go hungry as I’d rather they eat"

"I know people who have gone to school and are professionals but they don’t make money"

"Yesterday I had nothing to give my daughter so I dug up a cassava plant and we ate it raw"

The future is reached by emigrating

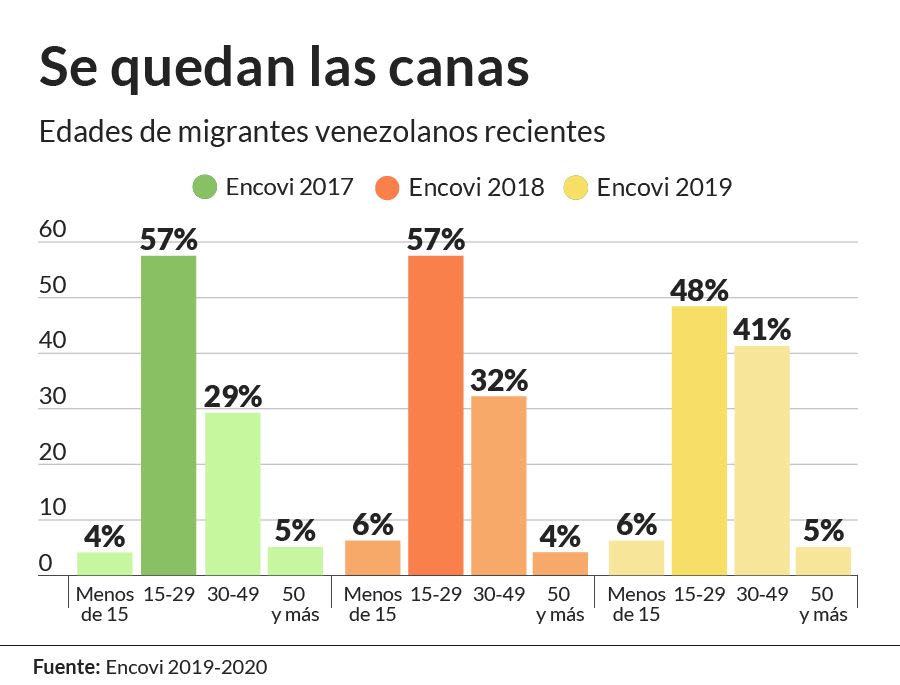

For the last five years, the average Venezuelan migrant is a young male who is either a father or a son. According to the National Survey on Living Conditions in Venezuela (ENCOVI), female predominance in emigration has declined to give way to a wave of men who in 2019 represented a total of 54% of those who fled the harsh living conditions of the country.

Wilmer Vallejo left his hometown of Caracas in November 2018. His decision was based on his despair at not being able to feed his children -at the time one and three years of age- as well as running out of options to find a stable job that would cover his most basic needs.

The final push Wilmer needed came when his older sister planned for both of them to search for opportunities in Ecuador. He left his wife and children behind at his mother in law’s in a tiny house located in the slum neighborhood of Macarao in southwestern Caracas. On November 7th, 2018, the packed “just the necessary items” in a small bag -actually all he owned- and set off on his journey to what he now calls “my new life”.

Across the border even by bus (Ronald Peña / El Pitazo)

Across the border even by bus (Ronald Peña / El Pitazo)

Now living in Peru, Wilmer remembers the great misgivings he had leaving his hometown, especially because he knew he would never return. The long road trip to Ecuador lasted between five and seven days. “I can’t remember exactly how long it took. What I do remember is that nobody prepares you for this kind of journey (…) I remember feeling tired and desperate after so many days of travelling on a bus. It was a mix of inexplicable feelings”.

In 2018, the ENCOVI survey stated that 57% of Venezuelan migrants were young adults between the ages of 15 and 29. They were predominantly male, a trend that would rise in the forthcoming years, with an additional increase of young adults and people with low levels of education.

Claudia Vargas, a researcher in the department of Social Science at Simón Bolivar University, ratifies that the current Venezuelan migration is mostly composed by men. This is related to the cultural phenomenon that places the male figure as the family’s provider. “Men leave thinking ‘I’ve got to send some sort of help back home. I have to support my kids; I have to support my parents’”.

This cultural notion was Wilmer’s motivation to leave and he remembers his days in Ecuador as “the toughest”. He knocked on many doors looking for a job but none were opened for him. He lived with his sister in Quito and survived thanks to odd jobs in carpentry, painting or selling sweets on the street. None of them provided enough for him to send money back to his wife and children.

Although he never planned to return home, he needed to generate enough income that would prove leaving his family behind worthwhile. He got together with some friends and began planning a new journey which would later on lead them Lima. They got there by walking and hitchhiking.

According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), 817,105 Venezuelans are still waiting for their application of refugee status to be accepted. With 60.8%, Peru is the country with the highest number of applicants. Among them is Wilmer who currently holds a card that identifies him as an applicant and grants him a certain legal status in his new nation. He arrived in Peru with only his Venezuelan identity card as a Venezuelan passport was a luxury he could not afford. It was best to save for what is currently an accomplished goal: his wife and children were able to join him.

Across the horizon is another border where one can truly make a life for himself

Across the horizon is another border where one can truly make a life for himself

An umbilical cord known as remittances

Catalina Chacón thought old age meant that she would be able to enjoy her long hard years of work as a teacher, spend time with her children and watch her grandchildren grow up. Reality, however, hit hard and over time her dreams have vanished.

Sitting on a wooden stool, Catalina cradles herself to a common beat in many other Venezuelan homes. 19% of Venezuelans report to having at least one of their family members living abroad. Catalina’s two eldest children have left. Her youngest, Daniela, 22, is the only one she has seen in the last three years.