Until 2013, Venezuela was among the first 30 countries in the world with the greatest reserves of monetary gold. However, in a matter of five years these reserves have been evaporating. This is largely in part to the Central Bank of Venezuela’s lack of solid management. Controlled by public servants who are loyal to Nicolás Maduro, this formerly autonomous institution has become the axis of an ecosystem of alleged money laundering, sanctions and million-dollar business deals which have also included gold resources extracted from the controversial Orinoco Mining Arc.

Esta investigación la encuentra en español gracias al apoyo de nuestros lectores y clientes, y se puede visitar haciendo clic en este enlace

https://alianza.shorthandstories.com/BCV-la-exprimidora-oficial-del-oro-venezolano/index.html

In early March 2019, three thousand six hundred kilograms of gold ingots with stamped labels from the Central Bank of Venezuela (BCV for its acronym in Spanish) were retained at the Entebbe International Airport in Uganda, located around 6,866 miles away from Caracas. The ingots, dated from the 1940’s were part of the 7.4 tons of gold coming from Venezuela which arrived to the African nation on two different flights (one on March 1, the other on March 4) operated by the Russian owned Nordwind Airlines.

Valued at $300 million, these ingots were to be processed by the refinery African Gold Refinery Limited and sent afterwards to its final destination: Turkey. As they were not declared in Customs, the ingots were confiscated by the Ugandan police under suspicion of contraband.

However, three weeks after the confiscation, the glitzing load processed by Goetz Gold LLC, a company of Belgian origin with headquarters in Dubai, was released by order of the Attorney General of Uganda with the consent of the President of Uganda, Yoweri Museveni. After its liberation, no track of the BCV stamped ingots were to be found.

Goetz Gold LLC is owned by gold tycoon Alain Goetz, who also founded the African Gold Refinery which was to process the load in Uganda. The businessman has been accused by anticorruption organizations like The Sentry and Global Witness of being a part of a “blood gold” trafficking network. Blood gold is the term for informal mining of the precious metal extracted in conflict areas which helps finance crimes and wars and promotes human rights violations. The UN Experts Group on the Democratic Republic of Congo has also questioned Mr. Goetz for his lack of transparency in explaining his sources of income in that country which has been plagued by violence associated with the gold business. Mr. Goetz has denied these accusations to the press and has stated that the “conflicting gold does not exist”. He has also said that he has cut ties with the Ugandan refinery by selling his stock to “a Middle Eastern family”, according to a statement given to De Staandard in April 2019.

The case of the confiscated ingots in Uganda is merely an example of the subterfuges that the BCV has employed to dispatch Venezuelan gold to foreign buyers. These ploys are known for their shadiness and are intended to deviate economic sanctions and “help keep Nicolás Maduro in power” as the United States has claimed. After the dismantling of the oil industry as Venezuela’s main source of income, Maduro has relied on gold to obtain alternate resources and gain liquid assets. All of this in the middle of a financial draught and the world’s highest hyperinflation.

The Central Bank of Venezuela is the axis of a silent but millionaire centrifuge of Venezuelan gold. Although the nation’s Constitution states that this bank shall be autonomous and independent from the government’s policies, reality has proven otherwise. Currently, the BCV has ceased to fulfil its task of overseeing national monetary stability and maintenance of an adequate level of foreign-exchange reserves. In turn, it has become a gold squeezing machine, the country’s main active reserve, as evidenced by this report created by Runrun.es in alliance with the Latin American journalism platform Connectas and the support of the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ).

The BCV is not only taking ingots out of its vaults to sell them in the international market. According to former public officials and experts interviewed for this report, they also take advantage of legal mechanisms and their own trade competencies in the gold market to “launder dirty gold” bought from the Orinoco Mining Arc (AMO for its acronym in Spanish). This State-run mega mining project has been marred by governmental corruption and control of irregular armed groups. It has also been put in question for generating environmental destruction and violating human rights.

It is worth noting that, contravening constitutional orders, the BCV does not report nor publish results of its gold-related policies. Therefore, the sum of this entity’s anomalies has been met with widespread criticism by local and foreign actors.

In April 2019, the US Treasury Department sanctioned the BCV with the aims of restricting its access to American dollars and therefore blocking the bank from making foreign transactions. “The Central Bank of Venezuela has been crucial to keeping Maduro in power, including through its control of the transfer of gold for currency”, said former national security advisor John Bolton. Already in November 2018, the United States had issued an executive order to sanction all operations related to Venezuelan mining.

The Maduro administration was quick to condemn the American sanctions. An official statement released on Twitter on April 17, 2019 said that these sanctions were “inhumane” and “another aggression against the people of Venezuela”. The government also said that the sanctions intended to block the bank’s operations and its relations with American and global financial operators “to achieve its collapse and begin a new colonization”.

#COMUNICADO | Gobierno Bolivariano denuncia una agresión más en contra del pueblo venezolano, por parte del Gobierno de Donald Trump, al aplicar medidas coercitivas unilaterales al Banco Central de Venezuela, afectando el bienestar y la seguridad de todos los venezolanos. pic.twitter.com/hZ0kXmJqH3

— Jorge Arreaza M (@jaarreaza) April 18, 2019

The US not only sanctioned the bank but also went after one of its directors, Iliana Josefa Ruzza Terán who occupies two pivotal positions in the BCV’s gold management. Ms. Ruzza Terán is Vice President of International Operations and Manager of Foreign Exchange Reserves. Since 2009, this economist has been appointed to several positions within the public administration in offices such as Venezuela’s state-owned oil company Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PDVSA), the Economic and Social Development Bank (BANDES), the National Center for Foreign Commerce (CENCOEX), the National Development Fund (FONDEN), the Social Protection Fund for Bank Deposits (FOGADE), the Ministry of Industry and the office of the Vice-President of the Republic.

The appointment of the current directory of the BCV has coincided with one of the worst gold reserve drops in Venezuelan history. In June 2018, on the same month that the Maduro administration announced “Operation Hands of Metal” to dismantle gold trafficking groups in Bolivar State and control the contraband of strategic material, a new directory was appointed. This directory was not sworn in by the constitutional National Assembly but rather by the National Constituent Assembly (NCA for its acronym in Spanish) promoted by presidential decree on May 1, 2017 as a parallel organ aligned to the Executive Power’s policies.

General Manuel Ricardo Cristopher Figuera is the former chief of the Bolivarian Intelligence Service (SEBIN) -the Chavista intelligence agency- and until recently a close ally of Maduro. He claims that the directors of the BCV usually purchase gold from a company managed by Nicolás Maduro Guerra, son of Nicolás Maduro. According to him, this company has total monopoly over gold in southern Venezuela, where artisan miners sell the precious mineral at irrisory prices. It is then sold by the BCV at escalated prices.

During an interview for PBS on July 2019, the exiled military officer reiterated the information: “Nicolás Maduro and his family use the State’s platform, they use the Central Bank of Venezuela to smuggle gold out of the country. This government system is what I call a criminal corporation. They all contribute towards corruption. They are all accomplices”.

The BCV’s autonomy -initially established in article 318 of the Venezuelan Constitution- has been hindered ever since former President Hugo Chávez went on his television show “Aló Presidente” in early 2004 and requested that the BCV hand over “a tiny billion” from its foreign-exchange reserves to finance public projects. This request turned into a reform of the law that governs the Central Bank of Venezuela which ordered that any “excess” income be destined to the recently created National Development Fund (FONDEN) for the sponsorship of plans proposed by the President of the Republic.

Chávez himself continued with the annulment of institutionalism by demanding in 2011 that all Venezuelan gold reserves deposited in London banks be repatriated. This operation culminated months later with a caravan of the precious metal being driven from the Simon Bolivar International Airport to the headquarters of the Central Bank of Venezuela. This procedure made the ingots lose their “Good Delivery” registry, which is a required classification in order to be accepted with greater ease in foreign markets.

This loss of autonomy has been informed by the 2018 Venezuela Transparency Corruption Report who identifies the “submission of the higher organ of fiscal control to an active militant authority of the government’s party”. This completely contradicts Article 320 of the Venezuelan Constitution which establishes that the Central Bank “shall not be subject to directives from the National Executive and shall not be permitted to endorse or finance deficit fiscal policies”.

Runrun.es contacted the president of the BCV as well as each member of its board of directors by e-mail and regular mail for interviews. To date, no reply has been given.

Gold prices on decline

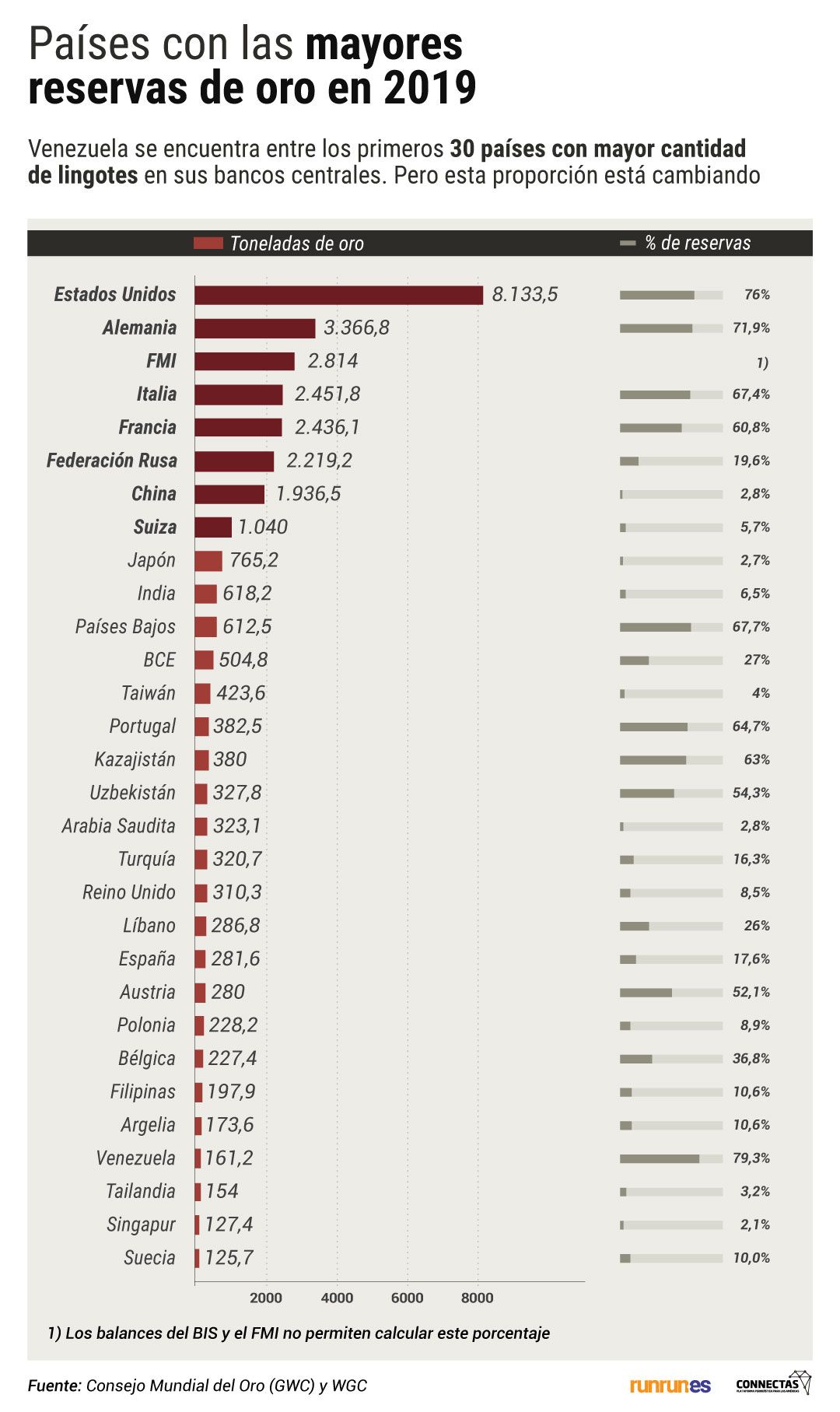

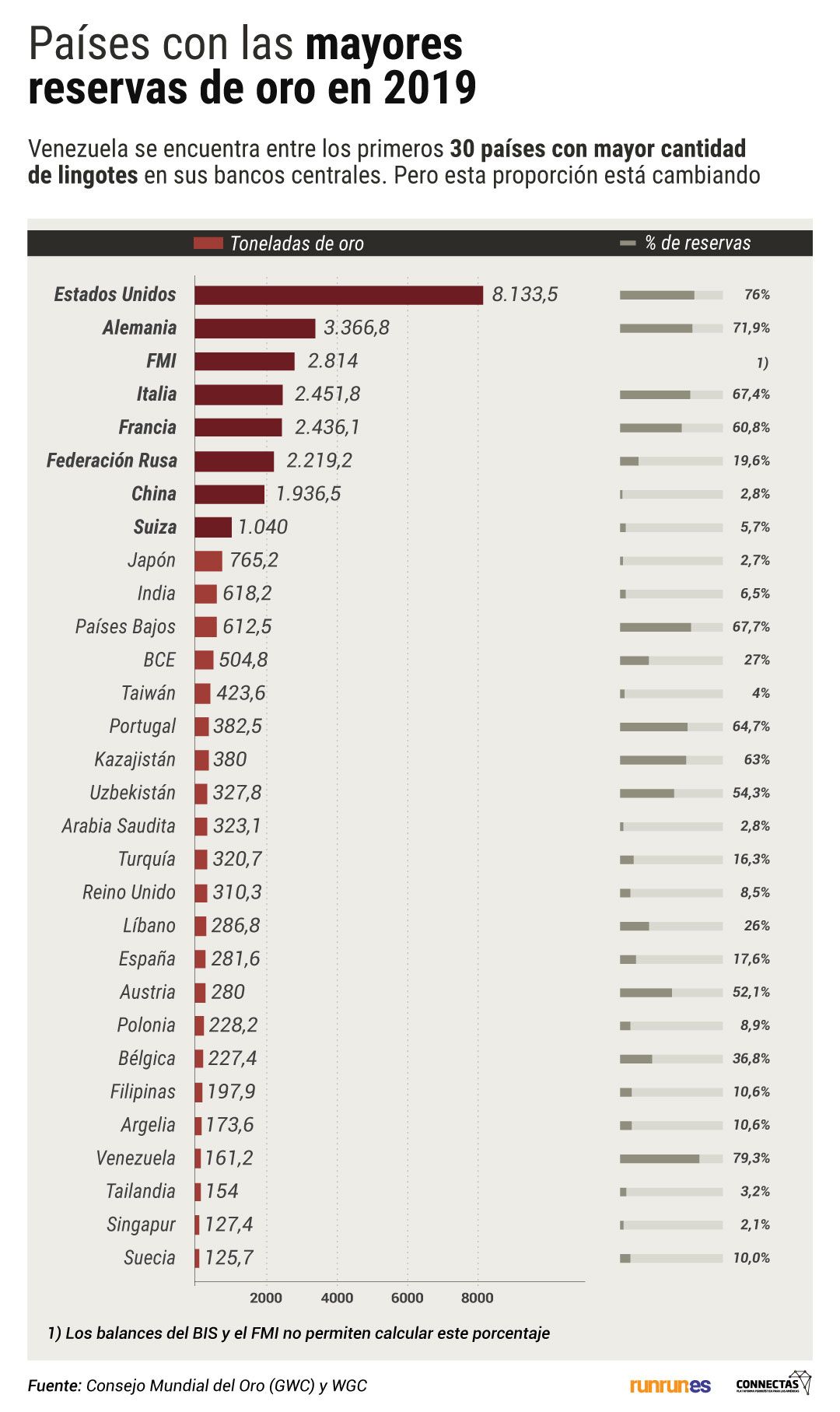

In the past few years, the BCV hast taken a peculiar behaviour. Unlike the global trend where central banks are increasing their reserves, the BCV has been the financial institution that has sold more monetary gold in the world for two consecutive years (2017-2018), according to the World Gold Council (WGC). For this international organ, the official sector continues to be one of the main motors in the gold market in 2019. Central banks bought 73% more gold than in the same period of time in 2018, reaching the highest figures in the last 50 years.

Accumulating reserves is seen as an indicator of monetary strength and stability. This is true for central banks from emerging nations as Russia, China, Turkey and Kazakhstan who in 2019 have been among the first countries to buy gold and transform it into reserves.

This is not the case of Venezuela.

According to the Venezuelan Constitution, the BCV may decide the purpose of the gold it stores in its vaults. The reason behind this is that the bank has permission to regulate and carry out operations, including trade, in the gold market. This also encompasses the ingots in reserve as well as the gold bars that come from Orinoco Mining Arc (AMO), decreed by Maduro in 2016 for the exploitation of strategic materials and which cover 12% of Venezuela’s territory.

In theory, all gold exploited in Venezuela must be reported to the BCV. Article 31 of the Extraordinary Decree No. 6,201 dated December 30, 2015 confirms that the strategic minerals obtained through any mining activity in Venezuelan territory shall be sold to the Central Bank. This decree also confirms that the bank is responsible for all gold trade.

In practice, not all gold produced by artisan miners ends up in the BCV’s vaults. The NGO Transparencia Venezuela calculates that only a third of what is produced in the Orinoco Mining Arc is reported to the Central Bank. The rest is smuggled out of the country.

Due to its autonomous nature, the BCV is not required to report to the Executive or Legislative Powers every time it wishes to trade gold. However, the economists Ronald Balza and Leonardo Vera agree that the bank “must report on the destination of that gold and the resources it obtains from those sales”. This is based on Article 319 of the Constitution which states that the BCV shall render an accounting of its actions, goals and results of its policies to the National Assembly as well as be subject to oversight by the Office of the General Comptroller of the Republic and the supervision of the public entity that supervises banking activities. The Constitution also states that failure to comply with these measures shall lead to the dismissal of the Board of Directors as well as the imposition of administrative sanctions.

Currently, the BCV does not report to the National Assembly as it should by constitutional obligation. Instead it reports to the unconstitutional National Constituent Assembly (ANC) created by presidential decree in August 2017.

On November 6th, 2018, two months and a week after his controversial appointment as president of the BCV, Calixto Ortega Sánchez submitted to the ANC the income and operational expenditures budget report for the 2019 fiscal year. He also presented five action lines that the Central Bank would take. Among them is “the strengthening of the nation’s international reserves to mitigate the adverse impacts external attacks have caused on the economy”.

A month later, the ANC approved the 2019 Budgetary Law in the amount of Bs. 1.5 billion (€ 3.400 billion). According to the government press, 75.2% of the budget would be spent on social investment.

Terrenos en Puerto Ordaz donde se anuncia que se construirá subsede del BCV, que servirá de centro de acopio del oro procecedente del Arco Minero del Orinoco. Foto: Lorena Meléndez

Terrenos en Puerto Ordaz donde se anuncia que se construirá subsede del BCV, que servirá de centro de acopio del oro procecedente del Arco Minero del Orinoco. Foto: Lorena Meléndez

Given the predominant secrecy in which the BCV works, the fulfilment of the principle of public responsibility is questionable. The bank does not publish reports on how much gold is being sold or who it is sold to. It does not specify if it sells ingots stored in its vaults or if they are uncertified gold bars that come from the Orinoco Mining Arc. Much less, what they will do with the resources obtained by its sales.

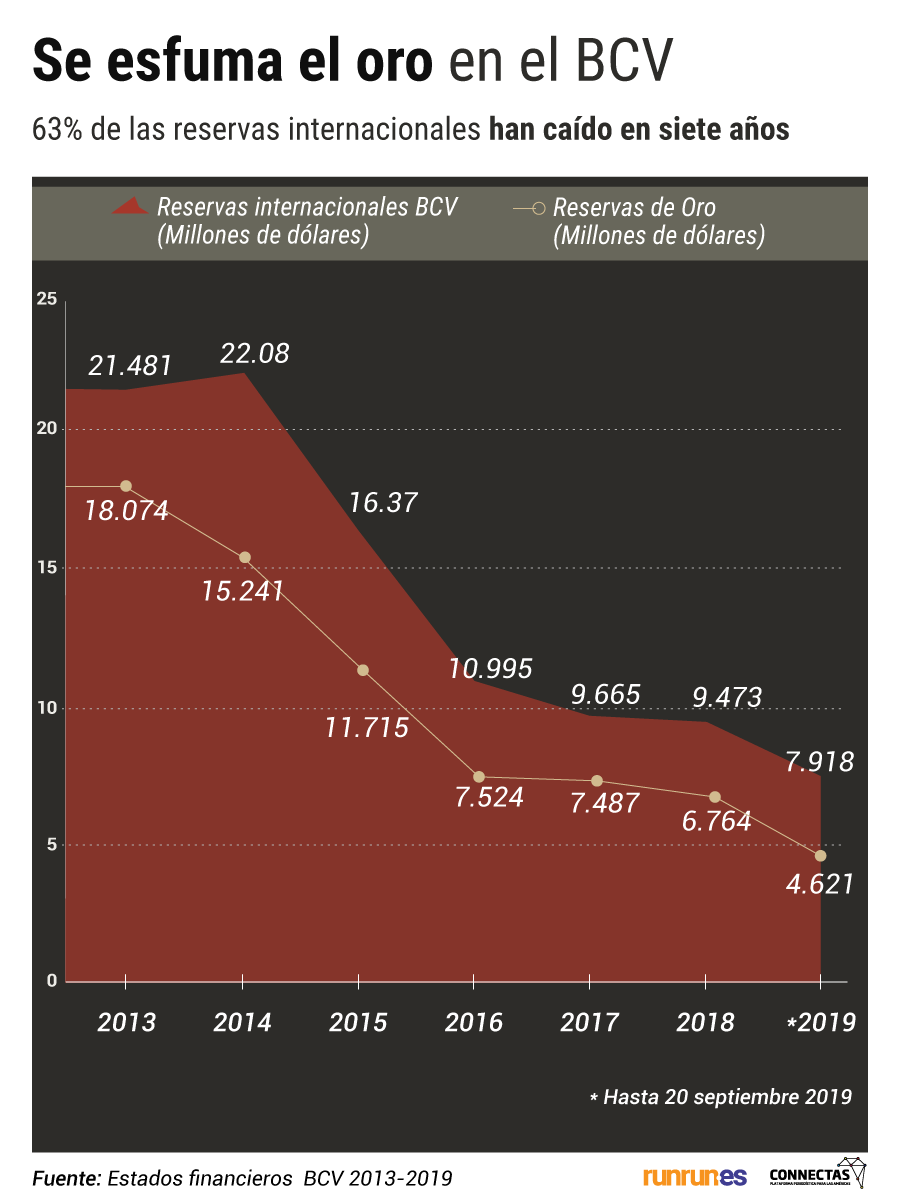

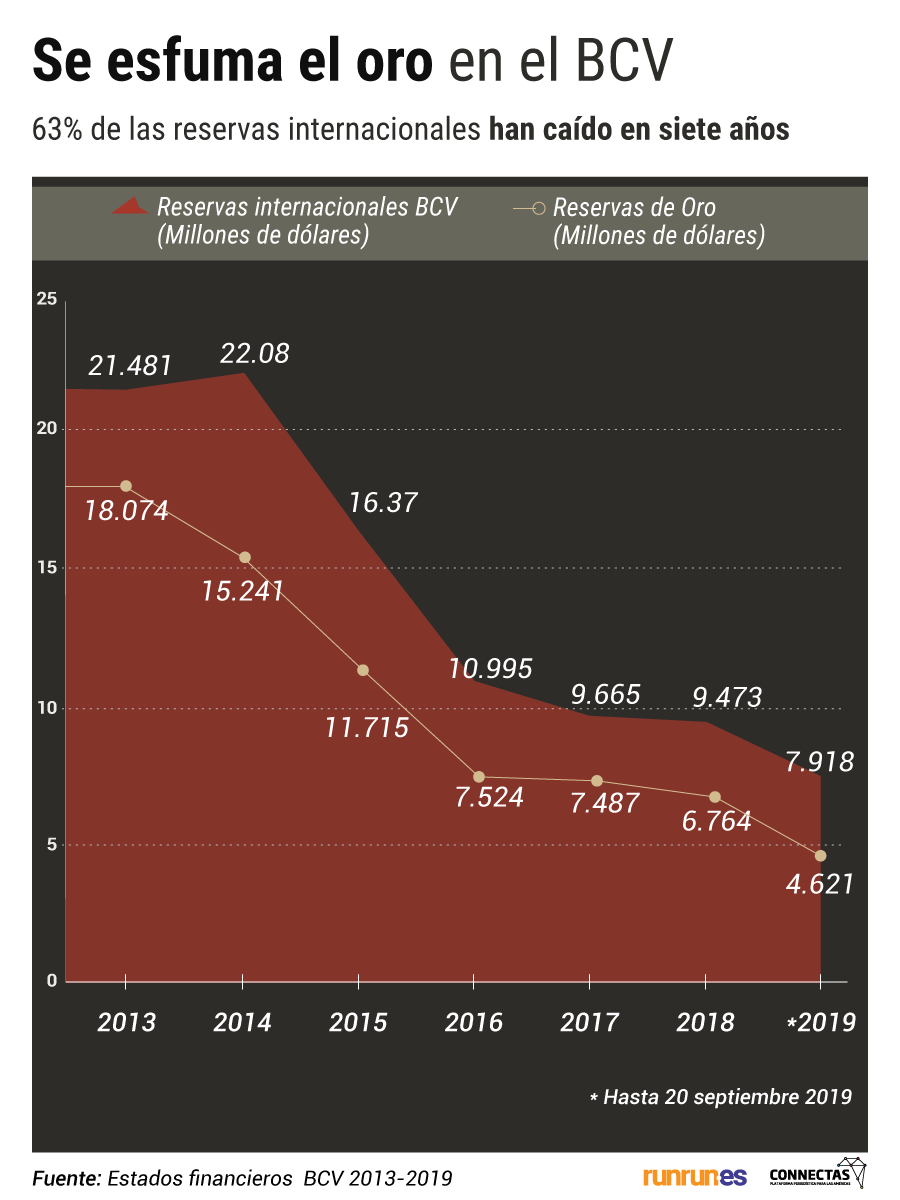

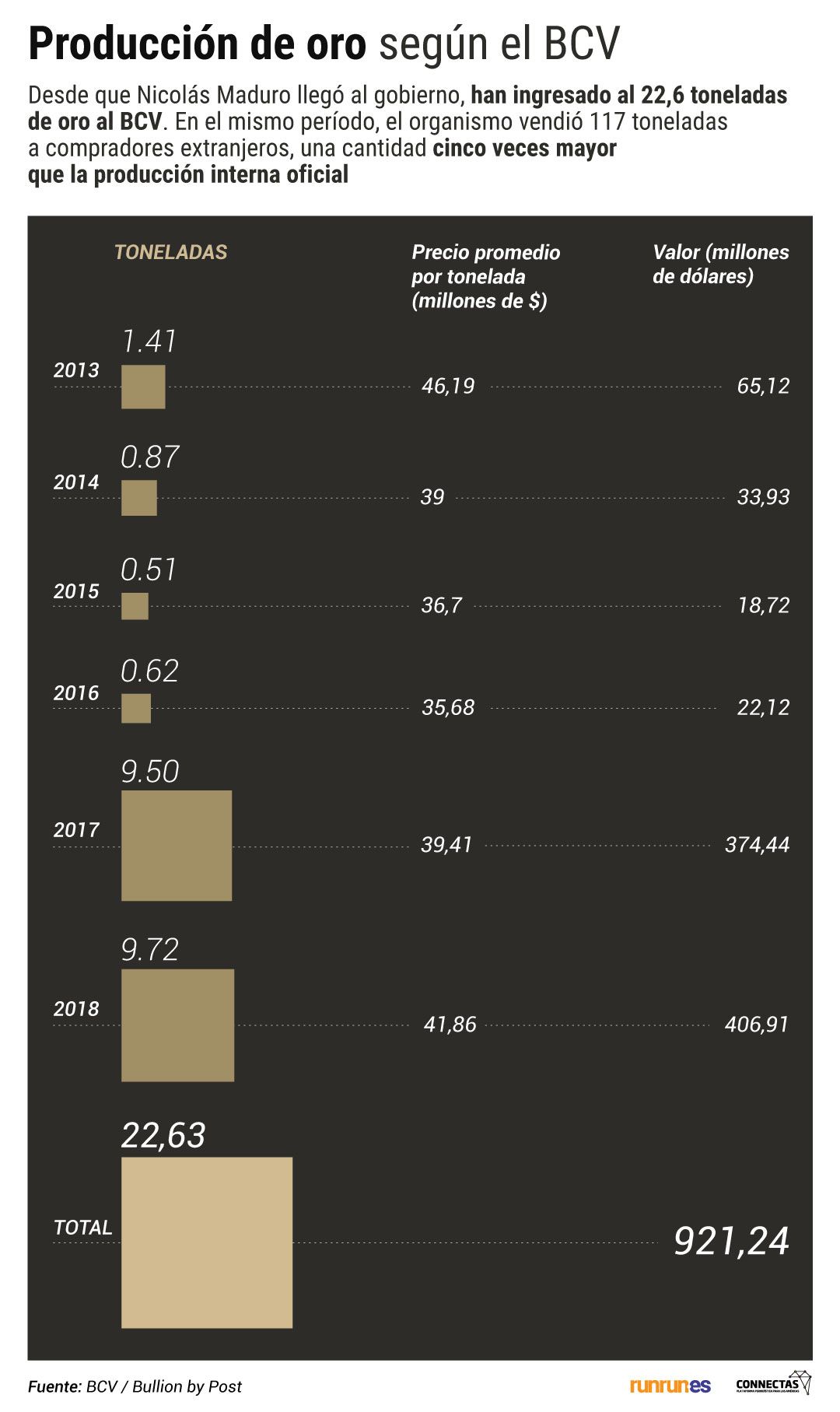

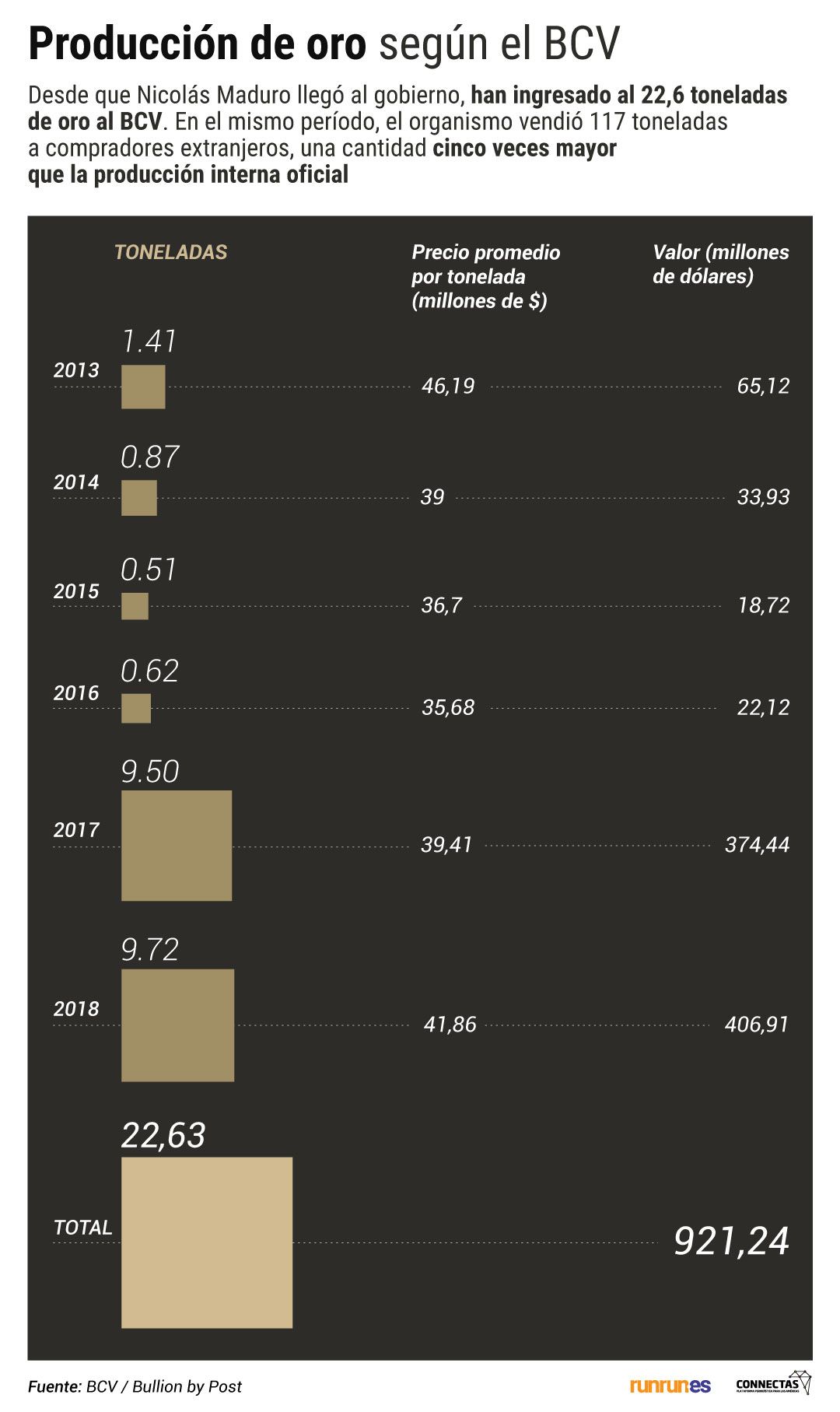

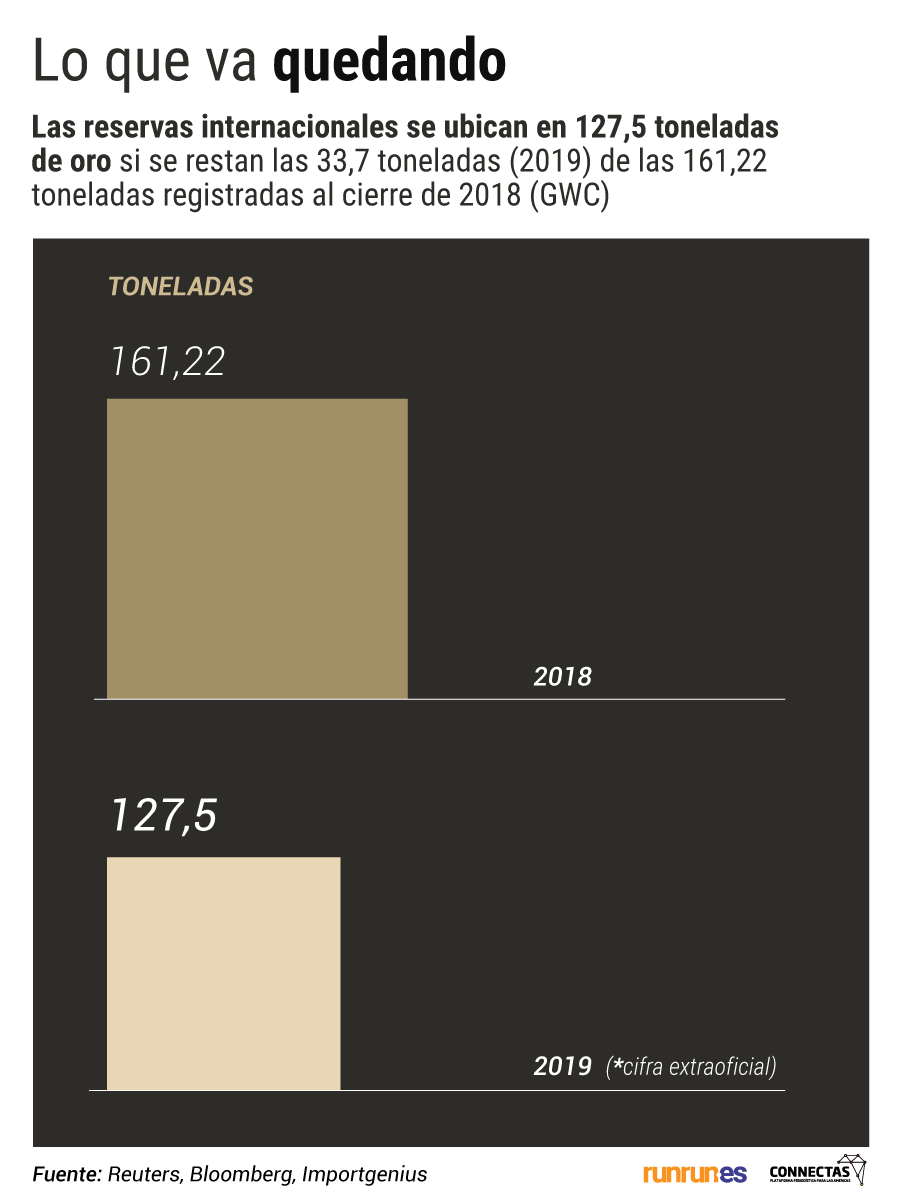

Ever since Nicolás Maduro became president of Venezuela in 2013, gold reserves have registered a 66.2% drop, reaching historical low-levels. According to the WGC, in a matter of five years, production passed from 360 tons in 2013 to 161.22 tons by the end of 2018. These figures have not been updated.

According to the BCV’s latest financial statement, a billion-dollar loss in gold reserves recorded in the first semester of 2019, coincides with the rise of under the table record sales of gold in 2018.

“This declining trend goes back to the 2012 electoral year where, according to Jorge Giordani, then Minister of Planning, ‘spending got out of hand”. These elections were won by a “gravely ill Chávez”, Mr. Vera reminisces. At the time, Venezuela was set to pay a 10 billion-dollar debt which should have been paid with oil revenues. The economist adds that a fall in oil prices led them to “cover the debt with liquid reserves”.

In 2017, Maduro began to have major problems with oil revenues, Mr. Vera notes. As such he began to cut back on dollar expenditures and imports, for example, dropped from $66.503 billion in 2013 to $29.810 billion in 2018 (a decline of 55%). The government began depleting foreign-exchange reserves until they ran out, says the economist. “They had to appeal to the only available asset they possessed: the BCV’s gold which became the fundamental component of Venezuela’s international reserves”.

Like any other central bank in the world, the BCV accumulates international reserves in order to be prepared for any unexpected event such as a drop in oil prices, declining exports and the payment of debt commitments. However, the Venezuelan institution has deflated the cushion created to meet financial instabilities and protect the nation’s monetary system, says Mr. Balza.

“Gold coming into the BCV is part of the “dirty gold” or “blood gold” that the central bank legitimizes through normative mechanisms and then trades legally in the international market. Some foreign refineries end up buying the gold that feeds criminal circuits in Venezuela”, says Frédéric Massé, director of the Center for Research and Special Projects (CIPE) at the Externado University of Colombia.

One of the main points BCV critics also mention is that the bank does not provide public information on the supply chains handled by its Orinoco Mining Arc providers. This uncontrolled area where crime reigns, has paved the way for claims such as the one mentioned by former SEBIN Director Manuel Christopher Figuera who has stated that Maduro’s son controls the gold which the BCV purchases. Before becoming a critic of the president and his administration, the general had been sanctioned by the United States for human rights violations in Venezuela, a punishment which has since been lifted.

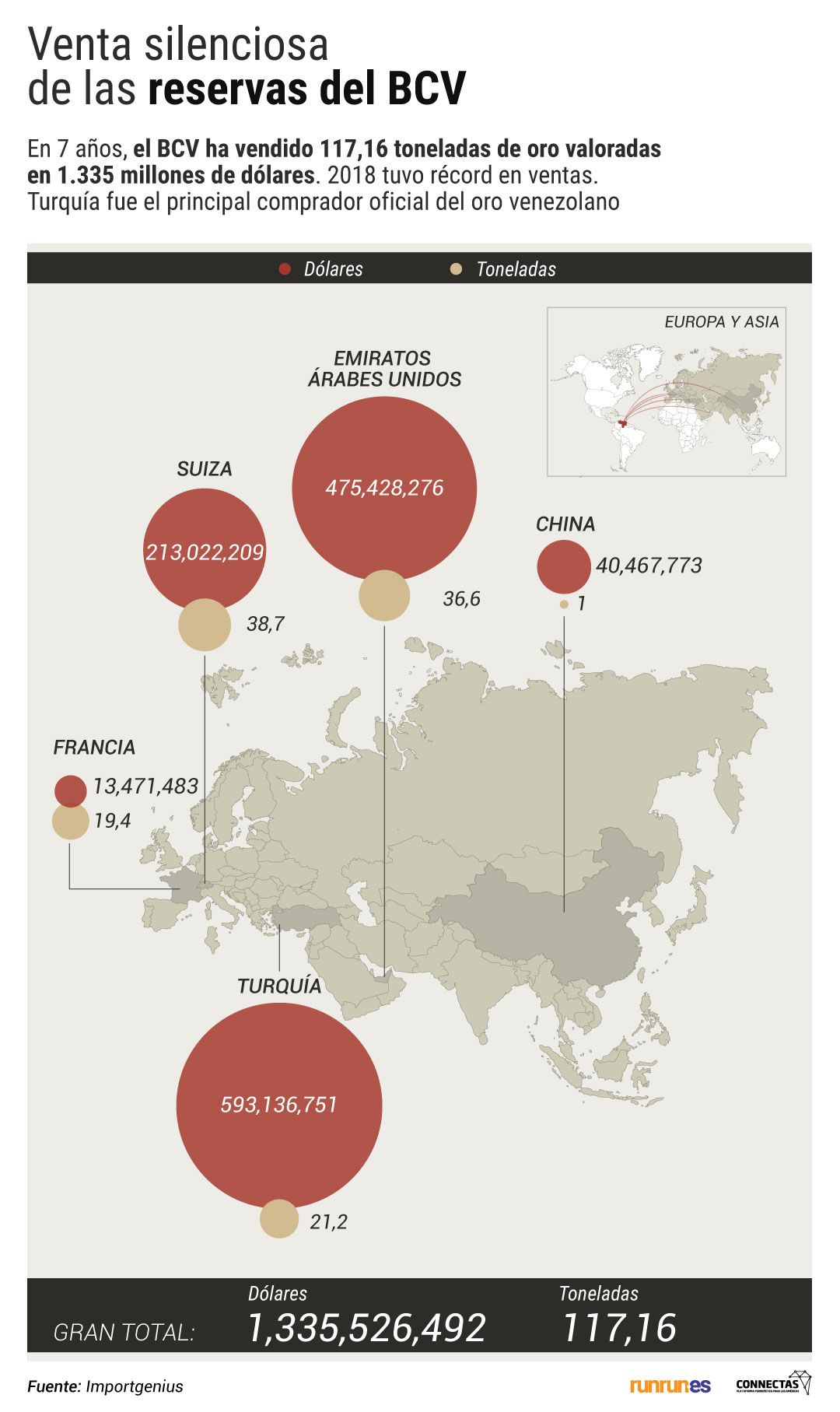

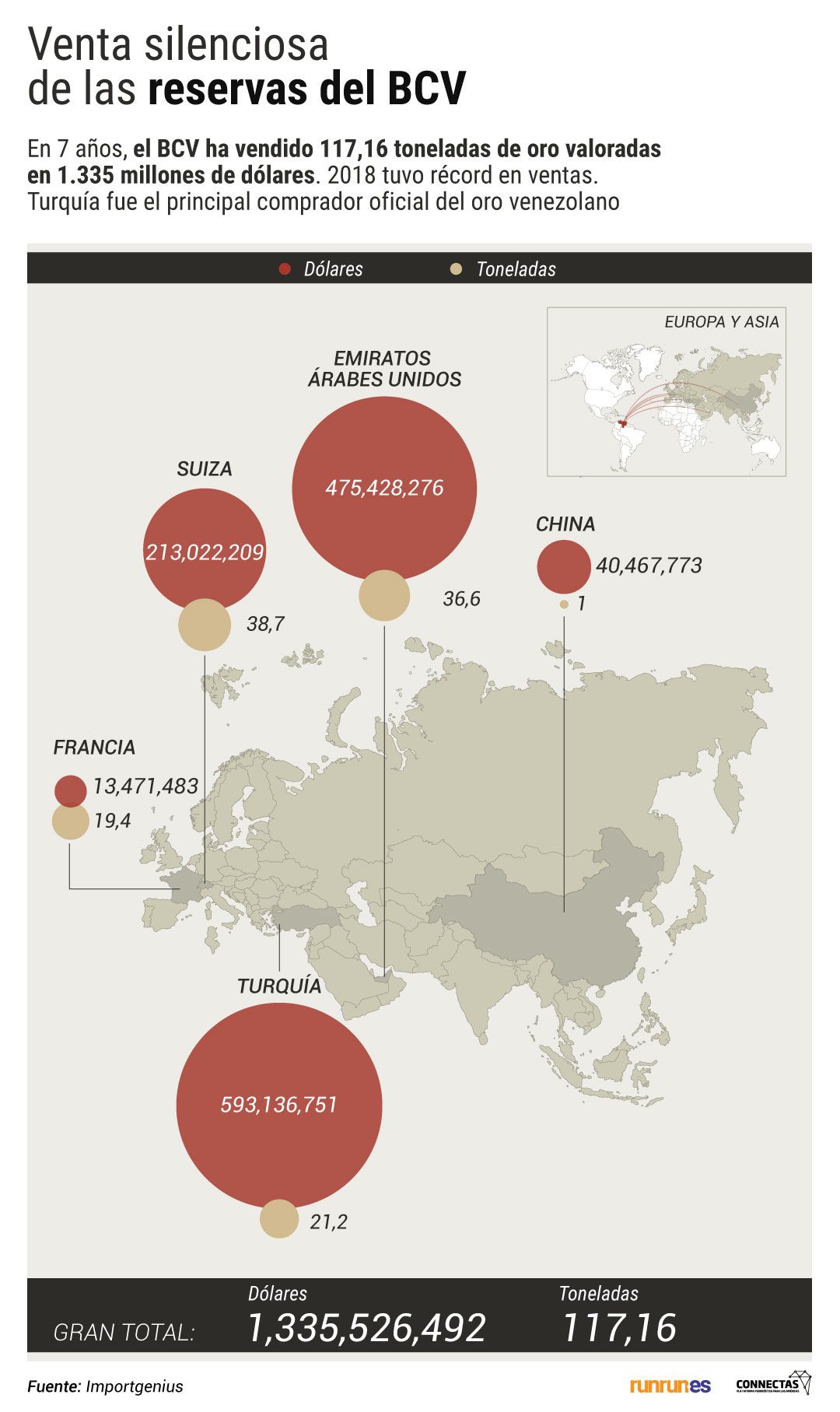

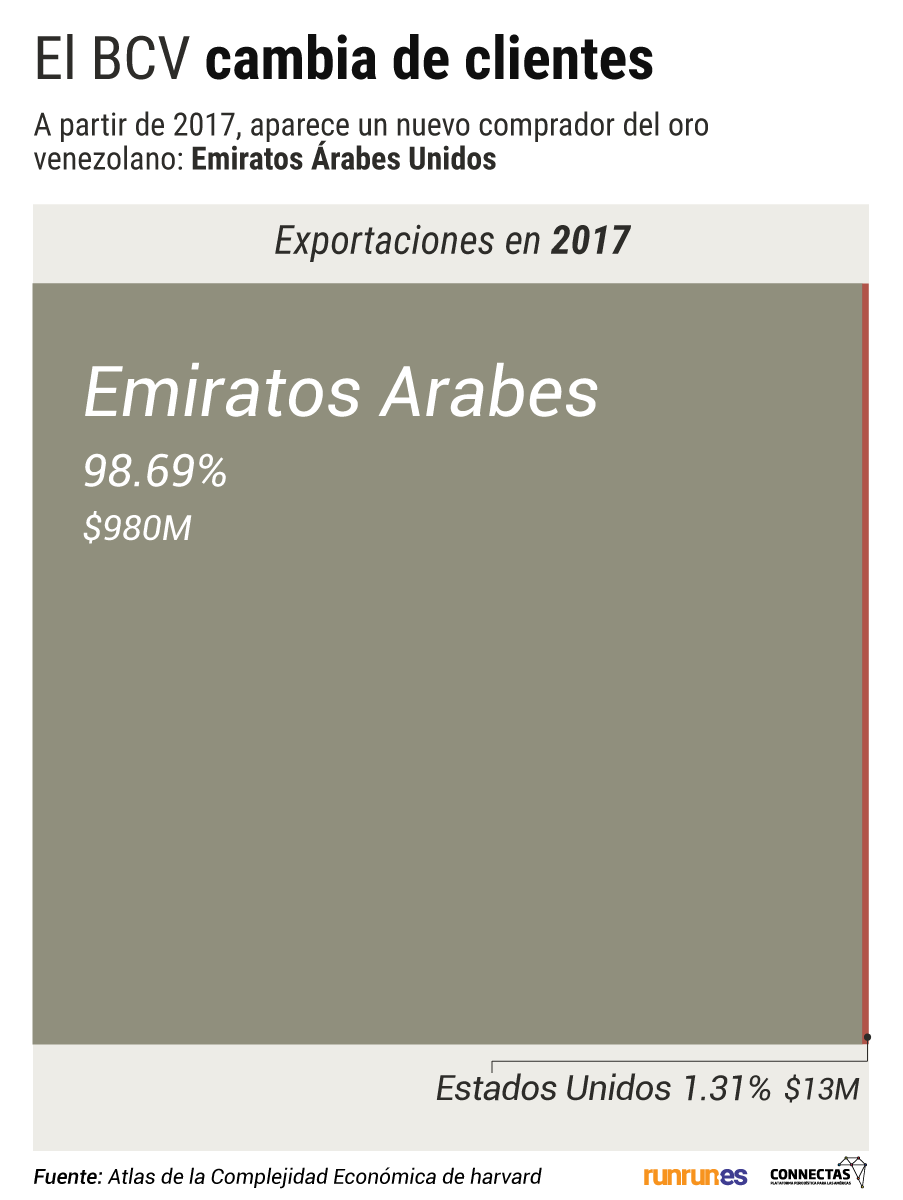

The economists interviewed for this report also state that US sanctions have led the BCV to increase domestic operations in Euros and augment trade with Turkey and the United Arab Emirates, two countries that purchase gold using European currency, according to Ecoanalítica consulting group. Since January 2019, the BCV has participated in the foreign-exchange market using Euros and forces Venezuelan banks, under threat of penalty, to sell Euros that come from sales of gold extracted in the Orinoco Mining Arc. By inserting this currency in the local financial system, the economists conclude, the BCV legitimizes resources coming from an activity which is suspiciously illegal in its nature.

Mr. Massé, who is an expert in the illegal gold market in Colombia and is an advisor to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OCDE) notes that the BCV follows the gold buyer’s monopoly formula which Colombia maintained until the early 90’s. In that specific case, legislation withdrew gold trade regulations and Colombia’s Banco de la República was stripped of its regulation faculties and control of gold sales, becoming just another agent in the market.

The result of this process was a drastic sales-drop to the Banco de la República going from 34.9 tons sold in 1991 (99% of domestic production) to zero in 2012.

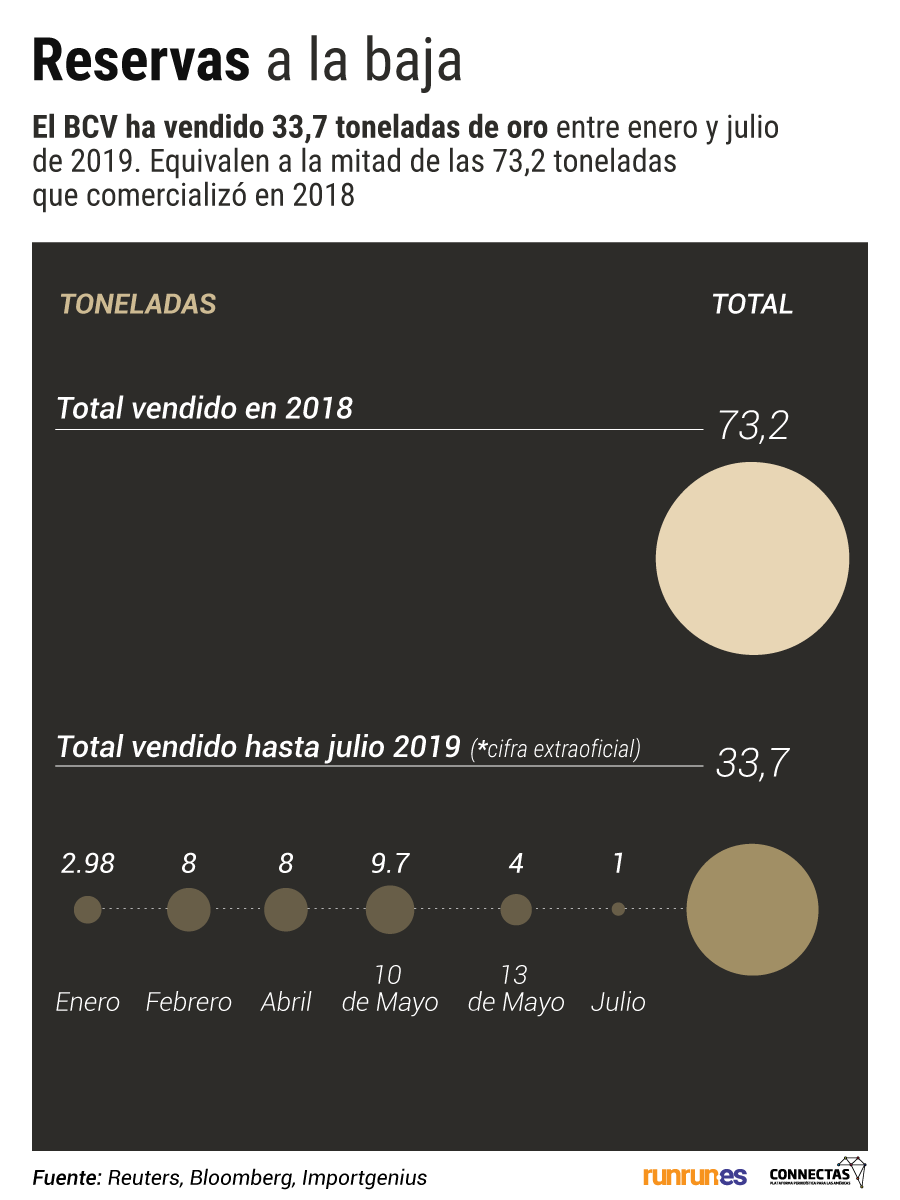

However, the case of Colombia’s central bank is not the same as its Venezuelan counterpart. Although theoretically the BCV holds a complete monopoly on any gold extracted and produced on Venezuelan soil, revenues of this precious metal are scarce in comparison to sales abroad. In 2018, while 9.7 tons made their way into the BCV’s vaults, the BCV sold more than 73.2 tons to a company in Turkey and two in the United Arab Emirates, according to claims set forth by several congressmen in the National Assembly and validated in an unofficial capacity by customs officers at the Simón Bolívar International Airport in Caracas.

73.2 tons of gold valued at $2.928 billion dollars left the BCV’s vaults and were transported to the international airport. According to a Runrun.es investigation, they were shipped off all along 2018 on 33 different commercial and private flights to Dubai and Istanbul.

Proof that the BCV is dipping into its reserves uncontrollably is that it keeps selling gold in quantities that do not match with what is reported as local production coming from the Orinoco Mining Arc.

According to Importgenius, between September 2011 and January 2019, the Central Bank sold 117.16 tons of gold at a value of $1.336 billion. In contrast, between 2013 and 2018 the BCV only reported 14.43 tons as national production which is eight times less.

However, a light increase occurred at the end of 2018 when the BCV made an internal purchase which was registered at 9.7 tons. This figure coincides with the 10-ton reserves increase identified by the World Gold Council and which is comparable to BCV’s own figures.

Open vaults

Located in the busy Urdaneta Avenue in midtown Caracas, the bold and sober lines of the Central Bank of Venezuela’s majestic building make reference to the serious nature of the institution created in 1936 to oversee the nation’s monetary policy and management of its reserves.

It was in that same building where one of the bank’s darkest episodes occurred. Allegedly, eight tons of monetary gold were extracted in the late hours of the night and carried onto Ford Runner SUV’s parked on the backlot of the BCV building. According to Congressman Ángel Alvarado, this event occurred between February 20 and 22, 2019, just before the February 23 events in which the president of the National Assembly and interim president of Venezuela, Juan Guaidó led an operation known as “Operación Libertad” (Operation Freedom) to allow the entry of humanitarian aid which failed to enter Venezuelan territory. By that date, the parliamentarian emphasized, the Chief of the bank’s Protection, Custody and Security division, had been previously pensioned off.

After the national blackout occurred in March 2019, the bank’s headquarters which are historically under custody were closed for a month and a half. The absence of employees and security guards led to speculations about the fate of the gold stored in the vaults located in the basement of the building designed by National Architecture Award recipient Tomás Sanabria. The weeks spent with lack of personnel coincided with the Bloomberg April 2019 report of the sale of eight tons of gold as well as a collection of gold coins from the XVIII Century.

Despite the sanctions imposed by the US to criminalize companies and persons who enter into operations with Venezuelan gold, the ingots from the BCV vaults have continued to make their way out of the country and traded in the international market. 2.7 tons of gold were sold to the United Arab Emirates in January 2019, specifically by Noor Capital, an Emirati company who admitted to the sale and later, after the imposition of US sanctions, decided to suspend the acquisition of another 11 tons of BCV gold.

If we take into account the 73.2 tons traded in 2018 and the 33.7 tons that, according to claims, had left the bank’s vaults in the first semester of 2019, it can be assumed that in a matter of 18 months, the BCV had sold more than 100 tons of gold.

How the looting works

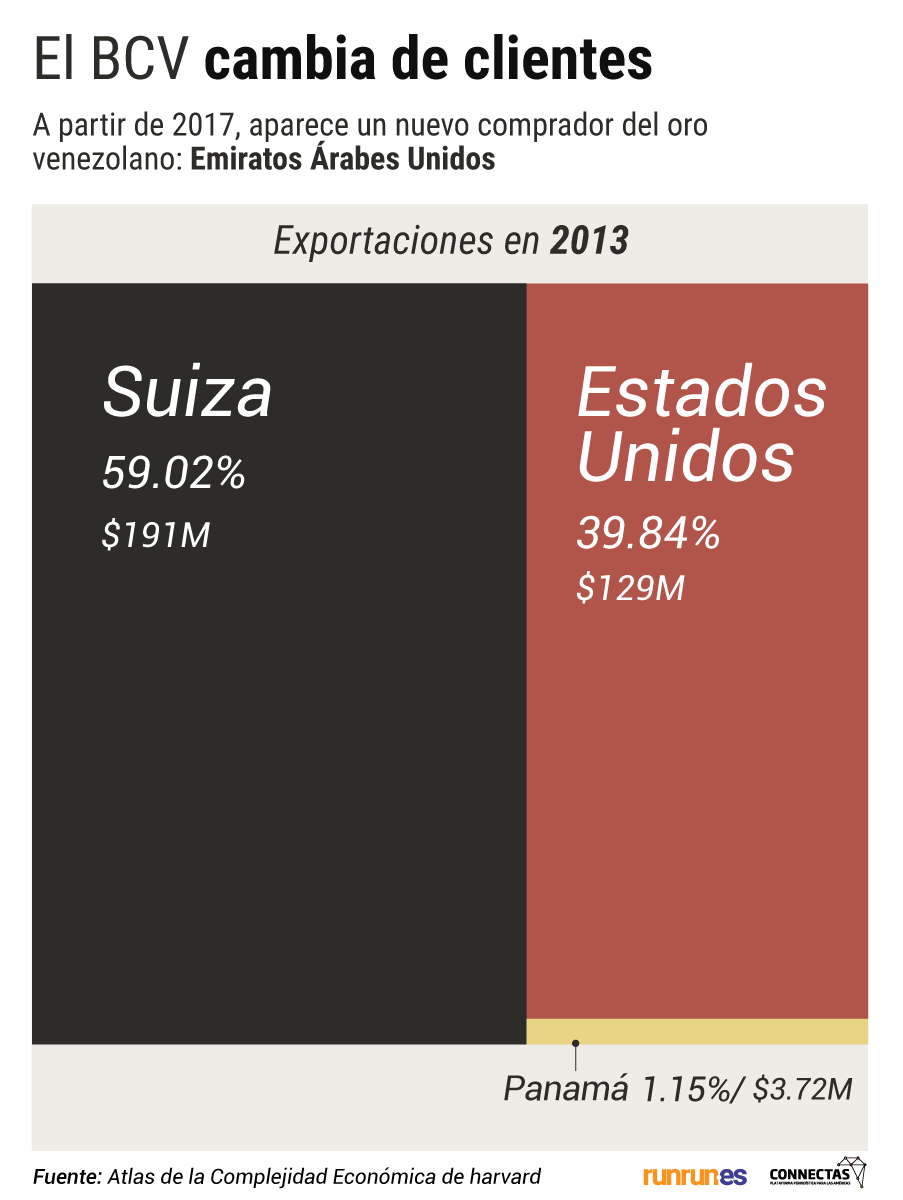

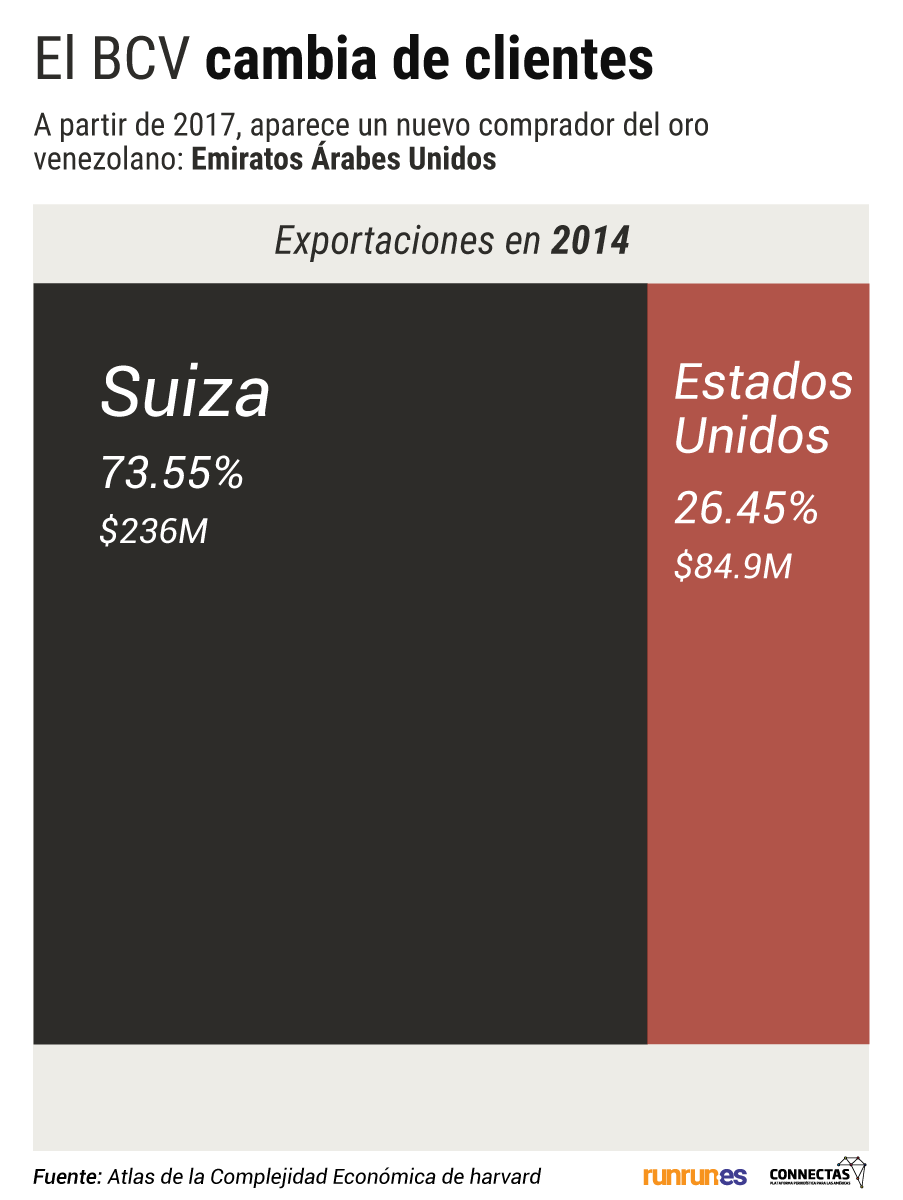

Gold sector operations were being handled quietly until the first sales of Venezuelan ingots to companies in Turkey and the United Arab Emirates became public in 2018.

The scarce traces left by the gold traffic route from Venezuela reveal a business relationship of at least two years with Goetz Gold, a Belgian company with headquarters in Dubai. Not only through legal routes with the BCV but more ambiguous ones through Aruba and Curacao as well.

In 2018, the BCV sold 21.8 tons of gold to this company which were transported from the Simón Bolívar International Airport in Maiquetía, according to Importgenius, the National Assembly’s Finance Commission and insiders at the airport.

However, evidence suggests that a year earlier Goetz Gold had already become a client of Venezuelan gold. Runrun.es and Infoamazonía gained access to a data base belonging to the Customs department in Aruba which indicates that Goetz Gold has been buying gold from Venezuela since 2017 and uses the Dutch Caribbean’s transit route. This prevents it from being registered as an official sale in Venezuela.

According to Aruba’s Customs department, the first load of 8.2 tons of Venezuelan gold valued at $4.379.599,53 was purchased by Goetz Gold on November 19, 2017.

There is also evidence of cross-trade operations. On September 2, 2018 gold coming from Venezuela valued at $2.130.698 was shipped from Aruba to the United Arab Emirates. This shipment was purchased by Premier Gold Refinery, a company with headquarters in Dubai whose main shareholder is Goetz Gold, according to data supplied by the United Arab Emirates Ministry of Economy office, to which Runrun.es had access to. Created in 2014 with a capital of $6 million, this company loans refinery and quality control services in the precious metal sector.

“In theory, an official institution such as the BCV should sell gold to another bank, not to an individual or private company. But that is precisely what Venezuela has done. It sells gold to traders or intermediaries such as Goetz Gold”, says Mr. Vera. The economist explains that this occurs as a means to avoid sanctions imposed by the US. “If Maduro’s government were to sell gold to a bank, it would have to sort greater regulations. Selling it to a private company is faster than selling it to a bank”.

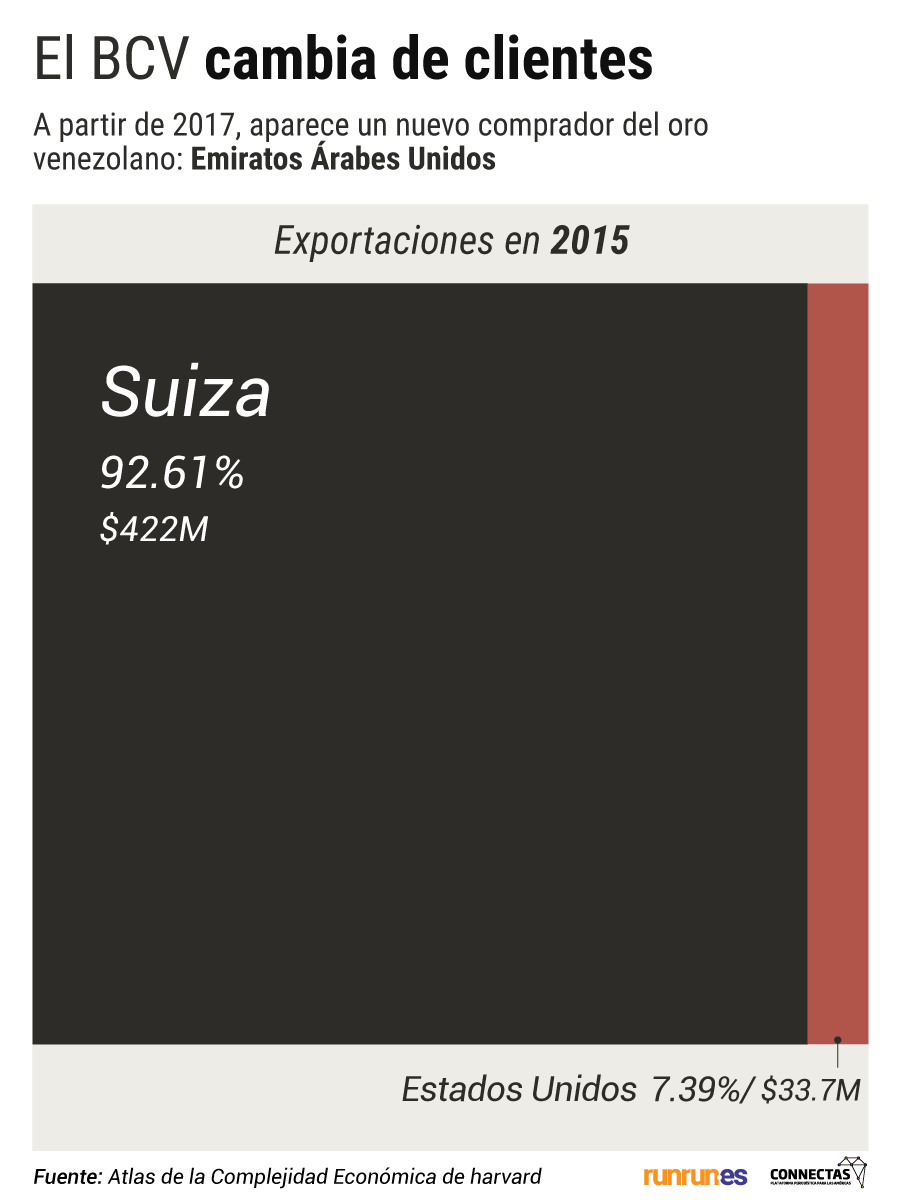

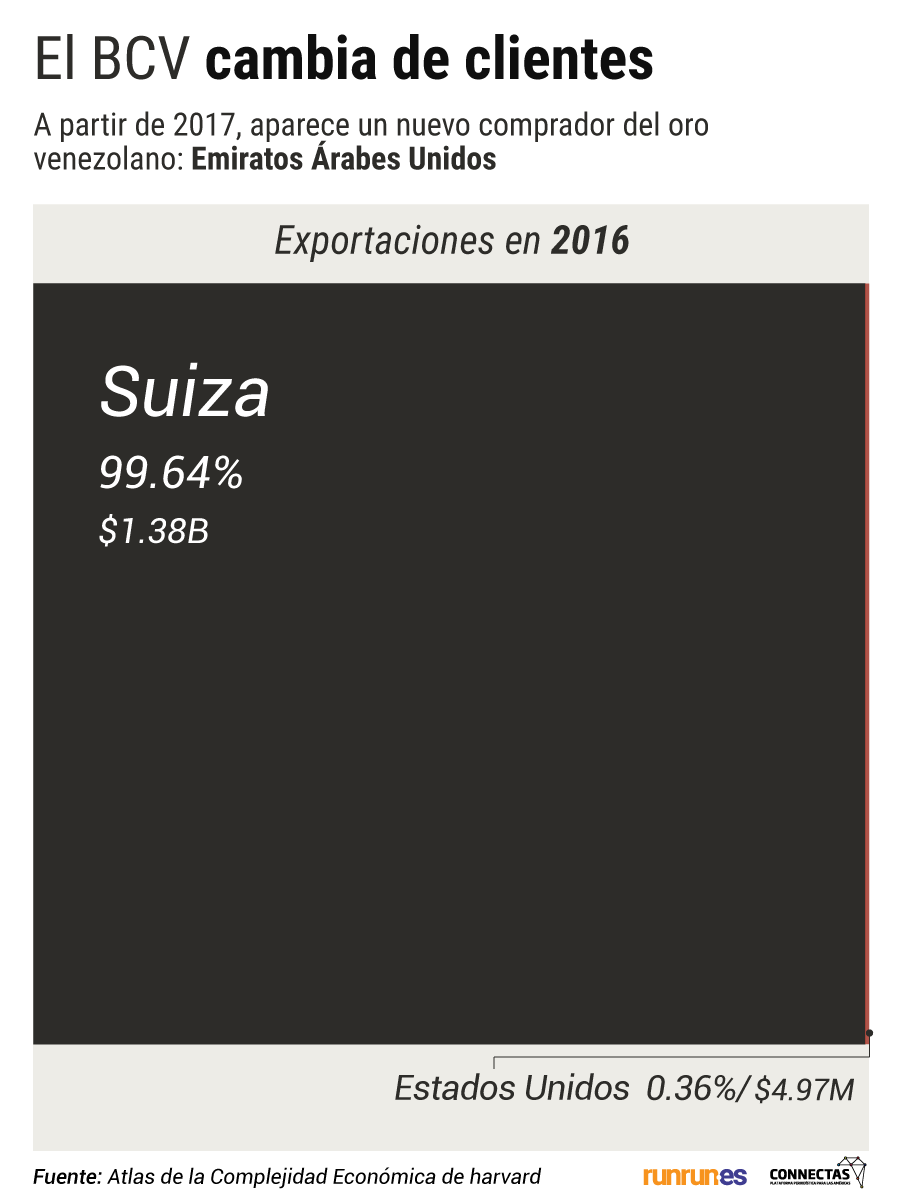

Importgenius, an international trade database and Harvard’s Atlas of Economic Complexity also mention the United Arab Emirates’ involvement in the purchase of Venezuelan gold.

Although trade relations between both countries go as far back as a decade, gold is a recent topic on the table. In a first bilateral agreement signed in 2010 by the then Minister of Foreign Affairs, Nicolás Maduro, and his Emirati counterpart, the Sheik Abdullah Bin Zayed Al Nahyan at the Yellow House, headquarters of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Caracas, both men discussed topics such as investments, associations, oil, gas and petrochemistry with the goal of creating a new economic map. Gold was not on the agenda nor was it five years later when the former Minister of Foreign Affairs, Delcy Rodriguez and Abdullah Al Nahyan met in Dubai to agree on policies to prevent tax evasion (sic.) as well as guidelines for the promotion of oil, gas and petrochemical activities between both nations.

La larga caravana del expolio

Gold controlled by a Maduro-friendly directory

When José Guerra, an economist who is a former officer of the Central Bank of Venezuela and currently a congressman in exile is asked about the state of the BCV’s institutionalism, he responds directly: “It is non-existent”.

Guerra says that the bank’s solemnity broke with the “tiny billion” episode. It fractured even more when people who respond to certain political ideologies were appointed to high ranking positions within the bank. Education and preparation for the job were left aside when Chavismo took over.

“It used to be that an appointment as director was based entirely on merit. Now they get the job only because they hold a United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV) member card. Before, directors were chosen using a scale that valued years of academic study with experience in the financial market. Technical experience was respected. Salaries were among the best in the public sector, second only to those paid by PDVSA”, he reminisces.

The last directory appointment was another sample of that breakthrough with institutionalism that the BCV was known for. It all began on Tuesday, June 26, 2019 when four of the six directors of the Central Bank of Venezuela – Pedro Maldonado Martín, Pablo Aníbal Pinto Chávez, Eudomar Tovar and José Salamat Kahn – offered their resignation. All of them were a part of the PSUV framework and were quickly relocated to several of the government’s ministry offices. Their replacements, explains Guerra, gave Maduro a greater political control on the bank.

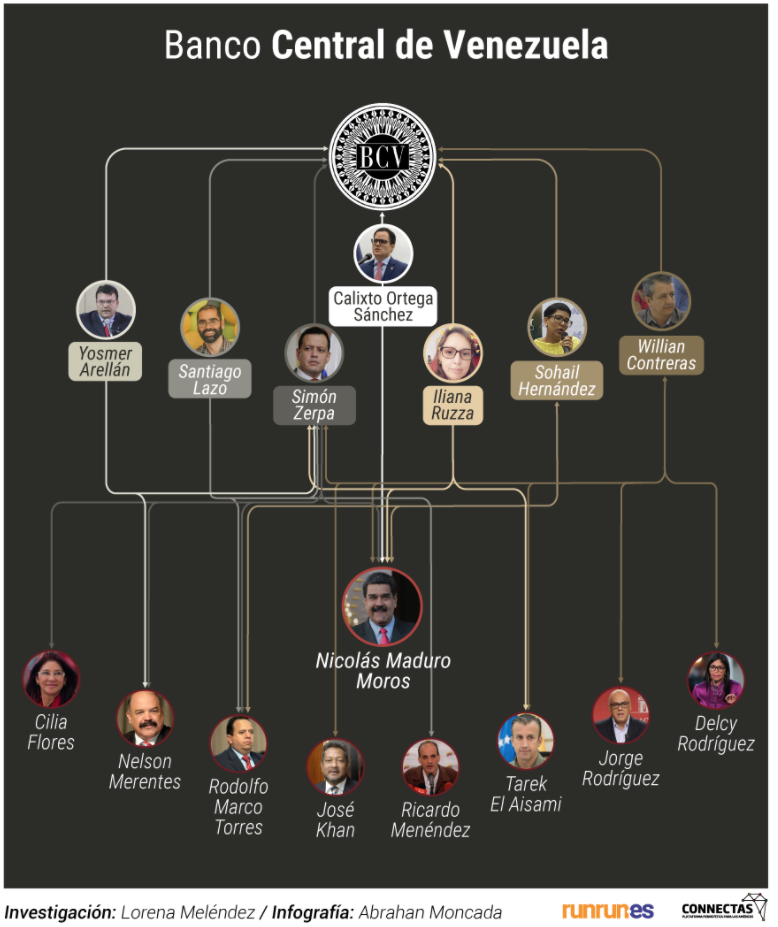

The resignation announcement was made by an illegal power: the National Constituent Assembly. A week earlier, they had approved the designation of the new president of the Central Bank: Calixto Ortega Sánchez, the thirty-year-old nephew of Calixto Ortega, former congressman and Justice of the Constitutional Chamber in the Supreme Court of Justice.

During that session, Diosdado Cabello’s first as president of the ANC, a “Committee for the Evaluation of Merits and Credentials for the appointment of members of the Central Bank of Venezuela’s Directory”. 16 days later, on July 6, 2018, the new directors were appointed according to Official Gazette Nº 41.434:. They were Yosmer Daniel Arellán Zurita, Iliana Josefa Ruzza Terán, Santiago Armando Lazo Ortega and William Antonio Contreras. Also appointed was Simón Zerpa who would serve as the bank’s liaison with the Executive Power. Months afterwards, Zerpa and Contreras would be sanctioned by the governments of the United States, Panama and Canada.

The five public officers joined Sohail Hernández in making up a directory that responds solely to loyalties. They all share direct links with Chavismo high-ranking officials, among them Tareck El Aissami, Vice-President for the Economic Area; Rodolfo Marco Torre, current Governor of Aragua and former Vice-President of the Central Bank of Venezuela; Nelson Merentes, former President of the BCV; Delcy Rodriguez, Vice-President of Venezuela; Jorge Rodríguez, Vice-President of Communication and Information and Nicolás Maduro himself.

These public servants have been employing these directors ever since they took their first steps in the public administration, giving them work in such offices as the Vice-Presidency, Foreign Affairs, Industry, Trade, Economics and Finances as well as institutions such as the National Development Fund (FONDEN), the Economic and Social Development Bank of Venezuela (Bandes), the National Center for Foreign Trade (Cencoex) and the Venezuelan Corporation of Foreign Trade (CORPOVEX), the National Steel Corporation and the Venezuelan Corporation of Intermediate Industries (Corpivensa).

According to Article 23 of the BCV’s internal handbook, among the directory’s functions are everything related to monetary and exchange policies as well as the definition of the Bank’s strategic direction. Besides, Article 23 states that the directors are in charge of determining the composition of international reserves and possess decision-making powers on their investment policy. They also regulate all matters related to the import, export, purchase, sale and encumberment of gold in any of its forms.

Long jump

The new directory members have one thing in common: in the last four years their careers have skyrocketed. Although all of them were employed as public officials during the Chávez administration, it is with Maduro in power where they have secured their power in the sector

An example of this is Iliana Josefa Ruzza Terán. A Bachelor in Economics from the University of Los Andes, she is a former classmate of Tarek El Aissami, the current Vice-President for the Economic Area. It was he who appointed Ms. Ruzza in at least two of the six offices she took over during 2018 at the Ministry of Energy and Oil, National Industry and Production and the Vice-Presidency of the Republic. At the BCV she is also in charge of the Vice-Presidency for International Operations and the Management of Foreign Reserves Administration. Mr. Guerra and Mr. Alvarado point out that Ms. Ruzza is in charge of all gold-related operations. In April 2019 she was sanctioned by the US Treasury Department.

Another director whose career seems to meet no limit is that of the Minister of Economy and Finances, Simón Alejandro Zerpa Delgado. A Bachelor in International Studies, in 2018 Zerpa was appointed to five different positions in institutions such as PDVSA, the World Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank. All of these positions must count with the nomination of the President of Venezuela.

Zerpa is not an ordinary director of the BCV. Rather, he is the bank’s liaison with the Executive Power and holds direct contact with Maduro. Therefore, his appointment was not designated by the selection committee but rather from Miraflores Palace itself. His relation with the Chief of State goes back to Maduro’s days as Chávez’s Minister of Foreign Relations, his first relevant public service position. According to Poderopedia, his father, Iván Zerpa Guerrero, the Venezuelan ambassador to China and former secretary of the National Assembly, was very close to First Lady Cilia Flores when she was president of the Parliament.

In turn, Zerpa Delgado maintains a close relationship with two other new members of the directory who were his subordinates at the Ministry of Economy and Finances: Yosmer Daniel Arellán Zurita, former Superintendent of Securities and Santiago Armando Lazo Ortega who has been a deputy officer at BANDES, the Inter-American Development Bank and Banco del Sur’s Administrative Council.

Another director is the current Minister of Domestic Trade, William Antonio Contreras. He became notorious for his surprise inspections when he became the Intendent for Expenses and Prices at the Fair Price Superintendency, an appointment he was nominated for by Maduro and reappointed by Zerpa in 2018. Contreras has also worked for the Ministry of Communication and Information and the Office of the Mayor of Libertador, which directly links him to two people of Maduro’s inner circle: Delcy and Jorge Rodriguez, the current Vice-President and the Minister of Communication and Information, respectively.

Completing the board of directors is Sohail Nomardy Hernández Parra, the only member of Khan’s directory who did not resign last year. This economist has been pointed out for her close ties with Maduro and also for interfering with the decisions taken by Ricardo Sanguino when he was president of the Central Bank, according to Crónica Uno. She has repeated this behavior with Ortega Sánchez, says congressman Guerra.

At the head of operations is Calixto José Ortega Sánchez, the president of the Central Bank of Venezuela who Maduro appointed in 2018. His career has been mostly abroad. In the US, he served as Venezuela’s Consul General in Washington, Houston and New York. According to Bloomberg he was senior adviser and vice-president of Finances at CITGO. When the Trump Administration revoked his visa, Ortega Sánchez returned to Caracas and took over the reins of the nation’s most important financial institution which in the past year has seen a historic downfall in its reserves.

An institution under surveillance

April 2019 was another month of sanctions for Nicolas Maduro’s administration. On the 17th day, the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) of the US Department of Treasury added the Central Bank of Venezuela to its list of “Specially Designated Nationals”. In a matter of hours, the main financial institution of Venezuela was classified by Washington as an entity which is under control of a nation that threatens or puts its interests at risk.

The sanction applied to the BCV meant that any asset the bank possessed on American soil would be blocked. It also forbids any American citizen or company to conduct any kind of economic business with the bank. Likewise, any Venezuelan operation conducted between the bank and an American company shall be immediately affected by the measure.

“Not only does it affect the BCV but also the entire financial system. U.S. banks will abstain from making any transaction where the Central Bank is involved”, explains Pedro Palma, an economist and director of the Ecoanalitica consulting group. Mr. Palma also points out that the measure is worrisome as the BCV is the main provider of foreign currency in Venezuela, given the nation’s currency control in effect since 2003, which has conditioned access to foreign currency needed to cover import necessities.

Therefore, the BCV has been included in the same list as more than 80 Venezuelan public officials and businessmen, as well as other entities of the State such as the Venezuelan Bank of Economic and Social Development (Bandex), the Bicentennial Bank, Minerven and the General Direction of Military Counterintelligence.

The Department of Treasury’s motivation to apply this punishment is based on the need to put an end to the transfer of Venezuelan of gold, which in the last few months had been serving Maduro for currency.

The day the sanction was implemented, former US National Security Advisor John Bolton spoke at a luncheon and stated the following: “The United States Will use all economic tools to the maximum capacity to constrict Maduro and ensure that his cronies no longer pilfer what rightfully belongs to the people of Venezuela”. Bolton also stated that the “steps taken against Venezuela’s Central Bank should be a strong warning to all external actors, including Russia, against deploying military assets to Venezuela to prop up the Maduro regime”.

Additional to the Central Bank’s sanction, the US Department of Treasury also imposed the same measure to the bank’s director, Iliana Josefa Ruzza Terán, said to be to the executor of all transactions related to Venezuelan gold.

Ruzza Terán is not the first in the directory to receive such sanction. Before being included in the bank’s board of directors Zerpa and Contreras had also been added to the OFAC list.

Zerpa was sanctioned on July 26, 2017 when the Department of Treasury declared that Venezuela’s corruption was heavily associated with two government entities. The first of these was Venezuela’s state-owned oil company Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PDVSA) from which approximately $11 billion went missing between 2004 and 2004, according to reports by the National Assembly. The second was the National Center for Foreign Commerce (CENCOEX) which facilitated the implementation of a black market surrounding the official exchange rate. Zerpa, who at the time was Vice President of PDVSA, was associated with the first.

At the time, Zerpa was also president of Venezuela’s Economic and Social Development Bank (BANDES) and the President of Venezuela’s National Development Fund (FONDEN).

Contreras was added to the OFAC list on March 19, 2018 for his lack of economic management and involvement in corruption.

“President Maduro decimated the Venezuelan economy and spurred a humanitarian crisis. Instead of correcting course to avoid further catastrophe, the Maduro regime is attempting to circumvent sanction through the Petro digital currency – a ploy that Venezuela’s democratically elected National Assembly has denounced and the Treasury has cautioned U.S. persons to avoid”, said Secretary of the Treasury Steven T. Mnuchin.

At the time, Contreras was the Superintendent of the Superintendency for the Defense of Socioeconomic Rights (SUNNDE), the agency responsible for imposing price controls in Venezuela, an entity which imposes price controls in the country and -according to an OFAC press release – have forced businesses to slow production or stop operations altogether.

“Contreras has been quoted as stating that SUNNDE implements government mandated price controls on raw materials and that these laws prohibit the private sector in Venezuela from declaring prices different from the government’s official price determination”, says the press release.

However, neither the sanctions to the BCV nor to three of its directors have prevented the outflow of Venezuelan gold. Although Noor Capital, the Emirati fund, upon hearing about the US government’s decision against the BCV, announced its decision to stop buying ingots from the Maduro administration, media outlets such as Bloomberg have reported that between May 10 and 13, 2019 nearly 14 tons of gold from the Central Bank’s reserves were sold off. On July 12, nearly $40 million were settled for a ton of the precious metal.

All of the economists interviewed for this report agree that if this descending rhythm continues, Venezuela’s gold reserves will be reduced to a minimum by 2020. After exhausting the inventory, the Maduro administration will only be able to live off gold and other strategic minerals mining operations. Given the government’s neo-extractivism dynamic and as long as oil production continues to decline, Venezuela will be forced to export more gold, which will never substitute oil revenues. The BCV will continue to be there, the axis to the centrifuge.

Coordinator: Lisseth Boon

Journalists: Lisseth Boon and Lorena Meléndez

Design: Carmen Riera

Infographics and illustrations: Mayerlin Perdomo

Infographics and video: Abrahan Moncada

Editing: David González and Laura Helena Castillo

This Runrun.es report was made in alliance with the Latin American journalism platform Connectas with the support of the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ).