Although PDVSA disbursed more than $540 million for 18 oil tankers, only one of them was delivered, according to the analysis of 57 internal company reports obtained for this investigation. The former president of the State-run oil company distances himself from this component of the “Oil Sowing Plan” and questions the dismantling of the corporation’s naval fleet

In 10 years, Rafael Ramírez accumulated so much power in the Venezuelan oil sector that he spared no moment to display it. At one point as President of Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA), he called for a press conference. Among his statements, he said that he had notified the Venezuelan Oil Minister on the details of the execution of the “Oil Sowing Plan” (Plan Siembra Petrolera). A reporter interrupted to remind him of the fact that he was the Minister of Oil. Ramírez jokingly referred to the power he enjoyed by saying: “Yes. I sent the letter to myself”.

For almost a decade, between 2004 and 2014, he simultaneously commanded the regulating entity and the regulated corporation. This put him in a privileged position to manage and supervise the Oil Sowing Plan, a multimillion-dollar investment of public resources to be executed between 2005 and 2030 and which aimed to guarantee that the income coming in from the hydrocarbons market boom and which overflowed PDVSA’s vaults would secure a future for Venezuela and the public corporation. Today, this same company has been dismantled.

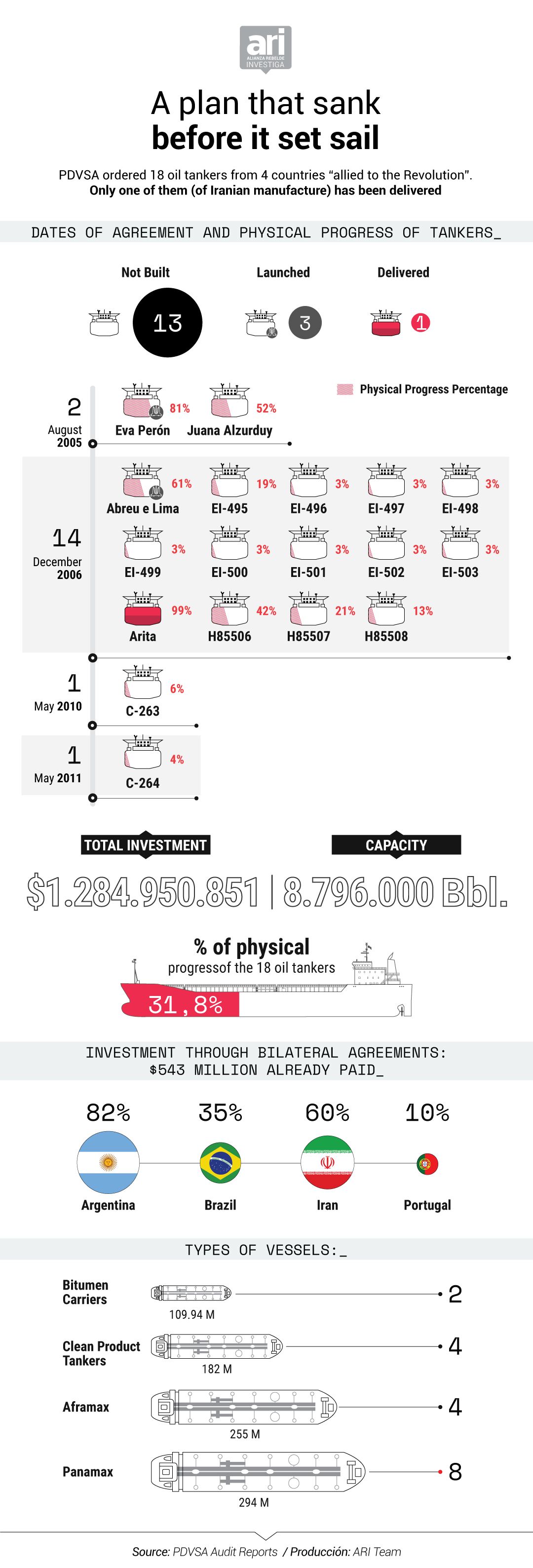

One of the Oil Sowing Plan’s ambitions ran aground before it even set sail. This was the acquisition of 42 oil tankers that would reinforce the company’s fleet. Of that hypothetical total, only 14 had been incorporated to the fleet by 2014, two years after the proposed deadline to concrete the purchases had expired. Four countries “allied to the (Bolivarian) Revolution” had signed agreements with Venezuela for the construction of 18 vessels. The result was the partial delivery of three ships, all of them with an uncertain completion date, and a single completed oil tanker which was added finally in 2019 to the fleet. The remaining 10 ships were only advertised but never built.

For these 18 oil tankers, 94% of which have not been delivered, PDVSA advanced nearly $543 million to suppliers. This represents approximately 42% of a $1.298 million budget that was allocated for their purchase. This amount represents a quarter of the net profit that the State-run company made in 2006, the year in which the late Hugo Chávez promised a future of prosperity for Venezuela and promoted the signing of contracts to build the powerful fleet he envisioned.

This is the basis of the following report published by Alianza Rebelde Investiga (ARI) made up by Runrunes, El Pitazo and TalCual, together with the Latin American online platform for journalists CONNECTAS. The conclusions are based on the examination of 12 reports validated by PDVSA’s internal corporate audit and other 45 monthly progress reports of its subsidiary PDVSA Naval (2012-2017), that this team of reporters had access to.

Surcharges, delivery of erroneous plans, breaches of contracts and inconsistencies in construction are just some of the irregularities reflected in the documents evaluated for this report. They largely explain the delay in the execution of the project for the purchase of these 18 vessels which until 2017, exactly 12 years after the signing of the first agreement, had a total physical progress of only 32%, according to the reviewed reports.

The oil tankers were ordered between 2005 and 2011 to shipyards in countries which were mostly governed by Chavez’s allies: ten to Lula da Silva’s Brazil; four to Mahmoud Ahmadinejad; two to Nestor and Cristina Kirchner’s Argentina; and another two to José Socrates’s Portugal. Combined, all of these tankers had a carrying capacity of 8.8 million barrels of oil, almost four times that of PDVSA’s daily production in 2014. As confirmed by former directors of the State-run oil company consulted for this investigation, none of them underwent a bidding process. Their approval was based on bilateral agreements that had been signed beforehand with each country. Venezuelan legislation allows direct procurement when it is within the framework of a government-to-government agreement, which in many cases was a stimulus for corruption inside and outside the oil company during the Chávez Administration.

Of the 18 oil tankers ordered, only the one manufactured in Iran was completed. It was launched into the waters of the Persian Gulf in 2012 and since then it has not been free of storms. An Aframax model, this tanker remained moored at the Iran Marine Industrial Company (Sadras) for seven years, loaded with debts and legal problems until 2019 when it was retaken by the Venezuelan oil company under a different name. The original plan of carrying oil to the Asian market was scrapped and today the ship only navigates through Venezuelan ports, as satellite records show. Meanwhile, the structures of another three vessels are berthed in the docks of Argentina and Brazil as can be seen by satellite imagery reviewed for this report.

The purchase of the other 14 tankers that were indeed added to PDVSA’s fleet until 2015 were also not exempt from sailing through rough waters. Four of them were Aframax models acquired to a Japanese shipyard with a 30% surcharge according to PDVSA internal reports and with the comparison of budgets approved for their purchase and market references anal analyzed for this investigation as well. One of them is used today to carry crude oil to Cuba.

Another four were acquired through CV Shipping, a binational company created by PDVSA together with PetroChina International, a subsidiary of the State-owned China National Petroleum Corporation. These were four Very Large Crude Carriers that are among the greatest carriers in the world. These tankers sail across ports between the Asian nation and South Africa. However, three of them have been seized by PetroChina Ltd. since February 2020, according to a Reuters news report dated August 11, 2020. The Asian company reclaimed them as a part of payment after CV Shipping went bankrupt.

The history behind the four Suezmax-class oil tankers, christened Río Orinoco, Río Arauca, Río Apure and Río Caroní, that were incorporated to the Venezuelan oil fleet in 2013 is filled with contradictions. PDVSA’s 2013 Annual Report indicates that PDV Marina received these four ships, named after large Venezuelan rivers, from the Samsung Heavy Industries shipyard in South Korea. However, in 2014 Rafael Ramírez announced the arrival of the Río Arauaca and the Ayacucho as part of an agreement with China, not South Korea. A year earlier, Reuters had informed that the Río Arauca and the Río Caroní Suezmax-class tankers were not really owned but rather “chartered”. The former president of PDVSA denied such claim, assuring that both vessels were registered together with PetroChina and “are fully operational and belong to us”.

Ramírez was contacted for this report. When asked to qualify the tankers acquisition plan and its results he said: “I don’t have the numbers with me, but the plan was good, reasonable and necessary. We had to do it”. The former public official said that despite specific problems with some suppliers, the purchases allowed to increase PDVSA’s self-owned fleet to 37 and achieve its capacity to take over almost all of its export operations. Ramírez stated that these acquisitions were made not only through allied government agreements but also through open international market procurement processes which allowed the participation of naval construction powers such as China, South Korea and Japan.

In reference to the evidence of excessive charges in the case of the Japanese oil tankers, Ramírez requested that the question be submitted in writing but no reply was given as this report went to press. He also failed to answer this investigation’s questions regarding actions taken by Asdrúbal Chávez, the current President of PDVSA, during his tenure as President of PDV Marina and PDV Naval. Both of these companies were key at the time the negotiation for the purchase of these tankers took place. In his statement, Ramírez maintained that more than 100,000 agreements were signed by the corporation every year and that its subsidiaries had financial and operational delegation to manage those agreements.

Surcharges, delivery of erroneous plans, breaches of contracts and inconsistencies in construction are just some

of the irregularities

The purchase of the other 14 tankers that were indeed added to PDVSA’s fleet until 2015 were also not exempt from sailing through rough waters

The dawning of investments_

Rafael Ramírez is Chemical Engineer from Los Andes University with a Master’s Degree in Energy from Central University of Venezuela. He became Hugo Chavez’s right hand in the management of the oil industry after the 2002-2003 oil crisis where PDVSA workers went on strike. Considered by the government to be an act of sabotage, the strike went so far as to forcing a shutdown in the industry. PDVSA’s oil fleet remained anchored and international sales were blocked.

Ramirez’s involvement with government came earlier. A year after Chávez came into power, he was hired to begin a national office that would regulate the gas industry. By 2002 he had become Chávez’s Oil Minister. A few months before being named the president of PDVSA in 2004, he joined the Commander in Chief as a member of the high-level delegation that visited Argentina. On July 8, at the Río Santiago shipyard in Buenos Aires, whose rundown facilities had been a matter of local pride in decades past, Chávez gave a speech where he revealed his plan to build oil tankers in order to renovate PDVSA’s fleet.

Joined by the President of Argentina, Néstor Kirchner, Chávez envisioned the beginning of a new era of oil tanker manufacturing with the support of allied nations. “I’m living a sort of dream”, he said as the public cheered on. At the event, he recounted the 2002 PDVSA oil shutdown and the impact private ships had on the conflict. “They wanted to overthrow me this way”, he said at the time. “But we took on the offense. We need a fleet of national oil tankers”. Chávez also claimed that PDVSA had $37 billion to invest in itself. A part of that money would be used to manufacture its vessels.

Six months later, on January 2, 2005 the project was formally launched. Asdrúbal Chávez, President of PDV Marina at the time, and Hugo Bilbao his counterpart at the Río Santiago Shipyard (ARS) signed the joint agreement for the construction of four Panamax-class vessels intended for refined products transportation.

Only two tankers began to be built at the Río Santiago shipyard: the Eva Perón and the Juana Azurduy. The formal documents that marked the beginning of their manufacture were actually signed in July 2007. The plan called for the delivery of the Eva Perón in two years and a half. The Juana Azurduy would be completed a year and a half later at the latest. Ten years later, advance work on the two ships was 81% and 51%, respectively, according to a 2017 PDVSA evaluations report. Currently, Google satellite imagery reveals that both vessels are exposed to rust in the shipyard.

These have been the results of a process that, despite fraternal speeches, have been filled with missteps. Documents obtained for this report reveal that the road has been not only tortuous but also filled with irregularities. According to one of the reports, auditors place the blame on both parties, including weaknesses in the control and supervision of costs. Disbursements for the two vessels have been in the amount of $123.7 million, almost 82% of the initial $151.3 million budget.

The most advanced vessel gives an insight about the comings and goings of the process. The delivery of the Eva Perón has been postponed on four occasions. It was even launched into the waters of the Santiago River in July 2012 although a third of its construction was still awaiting to be completed, as revealed by PDVSA’s audit and progress reports that this investigation had access to.

Just to mention an example, records of a meeting that took place on October 11, 2016 regarding the “initiation of an audit process and evaluation in the Construction Project of the Tankers in Argentina”, indicate that four years after the C-79 was launched into the river, the final coat of paint had not been applied in order to “prevent the accumulation of marine life in its hull” and that “taking the vessel into the dock to clean and apply the final coat of paint” was to be expected.

In June 2013, a year after the anticipated launch, ARS notified PDVSA that it was calling off the agreement and even forbid an inspection committee from the Venezuelan oil company to enter the shipyard’s premises. This conflict led to a meeting in Caracas a month later to renegotiate the project’s continuity. Nine months later, an amendment to the agreement was signed and a new schedule was established. According to a report from the aforementioned commission, the delivery of the vessel was slated for February 2023.

In December 2019, union workers at the shipyard stated that the oil tanker was 98% completed. At the time, Nicolás Maduro announced the disbursement of $22 million to finish both vessels. However, disbursement delays have been documented as one of the causes that has prevented completion of the project. In “due follow-up” given the “weak cashflow”, 550 days without payment were enough to contractually justify a postponement of delivery until 2016.

Unjustified payments also surrounded the project’s execution. Two examples are mentioned in the 2016 reports. One was the 35.2% surcharge in monthly payments made in 2013 and 2014 to a company hired by PDV Naval for the supervision and construction of the vessels. Another was a payment order not included in the agreement for $500,000 related to labor associated with the early launch of the Eva Perón without having completed five “prior and essential” operations.

These are mere brushstrokes of a project developed in choppy waters. Even Rafael Ramírez admitted to the reporters of this investigation that there had been problems with the agreement, even though he did not expand on details.

Forgotten in their shipyards_

The Argentine agreement opened doors for a second project of larger magnitude with a Latin American partner: Brazil. On December 13, 2006 days after an electoral campaign that re-elected Hugo Chávez as President of Venezuela, an agreement was signed between the two nations.

A month before, Ramírez gave a key speech which would alter the history of PDVSA. In this speech he declared that the oil company was “roja, rojita” (red, purely red) in reference to the government party’s colors. His words aimed to sweep any internal corporate regulation that forbid an open support to Chávez which ultimately opened a hole in a culture which was still resistant to politization.

The agreement to build oil tankers was signed by Asdrúbal Chávez representing PDV Marina in an alliance with three shipyards: Dianca, a Venezuelan company also adhered to PDVSA and the Brazilians Eisa and Maua Jurong. The contract contemplated the construction of eight Panamax tankers with a carrying capacity of 492,000 barrels of crude oil as well as two others with a carrying capacity of 346,000 barrels of products. This was the culmination of an idea proposed by Chávez and Lula da Silva in 2005.

Weeks before, another agreement had been made with a construction company named Andrade Gutiérrez to build a shipyard in Venezuela which would be capable of building super tankers in the Araya Peninsula, Sucre. A part of the Oil Sowing Plan, this $1.300 million project would be financed by national development banks from Venezuela and Brazil. Expected to become the largest shipyard in South America, the project never got off the ground. PDVSA’s decline, claims of political use of the Brazilian bank and the Lava Jato scandal, also reached Andrade Gutiérrez.

Plans for the oil tankers that were to be built by the Venezuelan-Brazilian alliance also met a similar fate: they never materialized. The budget for this project was $721 million, according to a 2017 PDVSA audit report of which $261 million had already been advanced. $167.5 million were meant for the construction of the Panamax-class tankers and $93 million for the rest.

Several disparities were found in the evaluations between the paid amounts and the physical progress of the project. For example, in the case of the oil tankers, there was a 3% progress calculation and yet expenditures surpassed a third of the total cost of $542 million. Additionally, 54% of a total of $173 million had already been paid for the construction of clean product tankers and yet the project had a little more than a third of total progress.

As reported by the media, the only vessel of the project which had shown advances in its construction was left abandoned at the EISA shipyard located in Governador Island, Rio de Janeiro. This was the Abreu Lima, launched into the waters in 2009 with 45% of its work left unfinished. In 2016, O Globo reported that inhabitants of neighboring slums considered the ship to be an enormous mosquito colony.

Delivery of the Eva Perón has been postponed four times. It was launched into the Santiago River in 2012 with at least a third of the work left uncompleted

An internal audit made in PDVSA in 2013 evaluated the 10 projects for the construction of the Brazilian vessels with less than favorable results. The audit report indicates that both the Panamax-class ships and the clean product tankers were under a “legal-technical evaluation of the agreement”. The document adds that “the development of the project is currently under legal conditions for international arbitration. This has been informed to the competent authorities such as the Corporate Legal Counsel and the International Litigation Management”.

Since 2009, the Brazilian media had reported on the differences related to the lack of due payment by PDVSA and a change in specifications of the vessels requested at a later date than what was established in the agreement. In August 2020, the owners of the shipyard were detained by the Federal Police for inquiries related to the Lava Jato Operation.

With Portugal there was even less progress than in Brazil and Argentina. On June 29, 2010, Chávez and the Portuguese Prime Minster, José Socrates, met at Miraflores Palace in Caracas to sign 19 cooperation agreements worth $2 billion. Among them, was an agreement between PDVSA Naval (led at the time by Asdrúbal Chávez) and Estaleiros Navais do Viana do Castelo for the purchase of two bitumen carriers. Rafael Ramírez was present at this meeting.

Five months later, Chávez travelled to Portugal and visited the shipyard to mark the beginning of the construction project. While there, he signed a contract with Joao da Silva, director of Portugal’s Espírito Santo Bank that would enable financing from the bank. He was accompanied, once again by Ramírez and Asdrúbal Chávez. Also present was PDVSA’s Financial Director, Eudomario Carruyo, who would go on to be accused of alleged links to corruption cases.

A budget of $145.6 million was allocated for the two bitumen carriers which would have a carrying capacity of 140 thousand barrels. Only a tenth part of the project was executed. Audit reports from PDVSA reveal that barely 5% of the work was completed. The reason behind this was the lack of cash flow. Initially, it had been announced that 95% of the project would be financed by the Portuguese bank. However, these disbursements never occurred and those issued by the Venezuelan oil company were only enough for the first year of salary payments.

The first carrier was supposed to have been completed by 2014. Although the shipyard bought more than 15 thousand tonnes of naval steel, construction never began. The material was sold by Viana do Castelo in 2017 for €8.7 million. It was the only memento of a shipwrecked project.

A project for the largest shipyard in South America never got off the ground due to PDVSA’s decline and the Lava Jato scandal

Controversial deliveries_

Out of the 18 oil tankers which Venezuela had agreed to obtain from four allied countries, only one, manufactured in Iran, was delivered. During an interview for this report, Rafael Ramírez mentioned that international sanctions imposed on that country in order to prevent its nuclear energy development plans had caused problems with the tanker’s construction. Although these sanctions meant that there were greater difficulties to disburse money through the foreign financial system, the Chávez Administration hired Iranian supply companies in numerous strategic projects, many of which suffered delays for the same reason.

Internal PDVSA documents reveal a different story behind the scenes. In December 2006, an agreement was signed for the manufacture of four Aframax tankers with a carrying capacity of 650,000 barrels of oil each. This contract was signed by the President of PDV Marina, Asdrúbal Chávez together with representatives of Sadras, the Iranian public corporation. Confidential reports of a PDVSA internal audit show that the investment was for $239 million at a price tag of $59.6 million for every ship. Until 2017, $176 million had been spent which represented 60% of the budget.

The first oil tanker was baptized after a Native Venezuelan chief: Sorocaima. According to PDVSA’s 2012 Annual Report, it was to be delivered that year. However, it was in July 2013 when the Iranian Vice President of Foreign Affairs, Ali Saeedlou, announced that the tanker, the first of its kind built in the Middle East, was “completed” and would be delivered “soon” to Venezuela.

Meanwhile, Sadras warned that PDVSA owed them $28 million that same year. Quoting the Iranian news agency Mehr, Reuters reported that the president of the company confirmed the existence of “problems with Venezuelan payments” but failed to mention if they would take legal actions against the oil company.

In 2014, the Sorocaima was still berthed at the shipyard, located on Sadras Island, Iran. Both Tradewinds and Bellingcat confirmed that the boat was still in the same dock, according to a record from the ship’s Automatic Identification System (AIS) which allows for global tracking. It wasn’t until February 2019, 13 years after the contract was signed, that the Sorocaima was finally added to PDVSA’s fleet, under the management of a subsidiary known as Albanave. This time, however, the tanker had a different name, the Arita, and it possessed a Panamanian flag, as confirmed by TradeWinds.

None of this stopped the storms from forming around the ship. Two months after beginning its trade activity, the tanker was detained in Singapore at the request of the German shipping company Bernhard Schulte Shipmanagement (BSM), who had previously been an operator of PDVSA’s fleet for an accumulated debt with the Venezuelan corporation.

Negotiation meetings held between PDVSA and BSM, the details of which are unknown, the arrest was lifted and the controversial Arita managed to reach the Amuay Refinery in Falcón, Venezuela in October 2019. Since then, the tanker navigates through Venezuelan ports, as certified by Marine Traffic, following a limited route which is far away from the ocean in which it was created.

Contrary to the official welcome other vessels had enjoyed in the past, the only oil tanker owned by PDVSA manufactured in Iran was not received with fanfare or confetti.

It was Rafael Ramírez himself who led a ceremony held in October 2013 to welcome the Ayacucho and the Río Arauca oil tankers into Venezuelan coasts. It was a festive event broadcast live on national television to celebrate the two vessels presented as having been built in China. Workers displayed a giant banner with the face of Hugo Chávez who had recently passed away on the Río Ayacucho, a tanker with a carrying capacity of two million oil barrels. The event, held at the José terminal in Anzoátegui, was moderated by Nicolás Maduro from Caracas via satellite.

“We carry our Commander Chávez in our hearts and our souls”; said Ramírez at the time. “Never before had Venezuela owned a ship of these characteristics. This is the first of eight oil tankers that will arrive in Venezuela. It’s almost the size of an aircraft carrier. It is the carrier of our Homeland, of our sovereignty, of the Revolution”.

In the end only four tankers with similar characteristics ended being manufactured in China. Just like the Ayacucho, the other three were named after Venezuelan battles fought by the Liberating Army during the War of Independence: Carabobo, Boyacá and Junín. The memorandum of understanding was signed on September 24, 2008 and involved CV Shipping PTE, a binational company controlled in equal shares by Venezuela and China.

Deliberations on the topic between both nations occurred more than once. One of them was during Chávez’s fourth official visit to China in August 2006. Meeting with Hu Jintao, President of the People’s Republic of China, Chávez mentioned the “strategic importance” of this trip. During his tour, he signed a first memorandum of understanding between PDVSA and China State Shipbuilding (CSSC) and China Shipbuilding Industry Corporation (CSIS), the two greatest shipbuilding companies controlled by the Chinese State.

Signed by Ramírez, the agreements main object was to “increase the Venezuelan oil fleet, reduce third-party dependency and ensure client satisfaction of energy demand with the construction of 18 oil tankers”, according to the statement given by the former Oil Minister and President of PDVSA.

Only four tankers from the original plan with China were delivered. On December 22, 2009, another oil tanker construction agreement was signed; this time between CV Shipping PTE Ltd., China Shipbuilding & Offshore International Co. LTD and the shipyard Bohai Shipbuilding Heavy Industry Co. LTD. Results from this agreement are unknown.

The Carabobo oil tanker was launched into the sea in September 2012 at the Bohai shipyard in the city of Huludao, whose operation would be in charge of CV Shipping PTE and would tend to the Asian market. However, the first tanker to arrive in Venezuela was the Ayacucho. On that occasion, Ramírez announced that the Boyacá would arrive before the end of 2013, followed by the Carabobo in May 2014 and the Junin in October 2014.

The four vessels in the Chinese agreement were found to be active by the end of July 2020 but not necessarily fulfilling the object for which they were built. Three of them are no longer a part of PDVSA’s fleet. Between January and February 2020, the Boyacá, the Carabobo and the Junín were seized by PetroChina Co. Ltd. after CV Shipping (owner of the tankers) went bankrupt.

There is no known reference of the price CV Shipping paid for these oil tankers as the shipyard alleged that the construction operation for these vessels was a “trade secret”. According to the shipping broker Gibson Shipping Energy, the average price for these types of ships is $95 million. It is worth noting that this investment was made by PDVSA through public funding. A negative result for an unknown millionaire investment of three ships that Venezuela no longer owns.

The drift was different with another Asian partner: Japan. In 2009, PDVSA signed an agreement to purchase four Aframax tankers with a carrying capacity of 720,000 barrels of oil. This idea was put forth by Hugo Chávez during an official visit to Japan that year.

The 2010 Annual Report for the Office of the Ministry of Oil mentions the agreements reached by the negotiations between PDVSA and Itochu Sumitomo Heavy Industries. In it, the report states that the purpose was to acquire oil tankers with an $87 million investment for each vessel. It also mentions that the project’s physical progress was already at 25% and that there was the pending matter of having PDVSA’s Board of Directors sign the four acquisition agreements. 70% of the total cost would be financed by the Japan Bank for International Cooperation.

On April 10, 2013, a month after the death of Hugo Chávez, a committee led by his successor, Nicolás Maduro, accompanied by Ramírez, received the four Japanese tankers at the port of Guanta in Anzoátegui. According to EFE, $312 million had been invested on this project. According to the late president Chávez, the vessels would cater to 40% of the Asian market.

The four oil tankers were named after Native Venezuelan chiefs. Clad in a Venezuelan flag jacket, Nicolás Maduro stated that the Paramaconi, the Terepaima and the Yare (formerly the Guaicaipuro), would “navigate through the oceans of the world carrying Venezuelan oil and its processed products. We have come here to ratify our full sovereignty on our oil”.

At that same event, Ramírez ratified that the four ships were part of a group of 26 oil tankers purchased from Japan. The rest, he assured, were still under construction and would allow for new “commercial and viable” routes to new markets such as China and India. To date, there is no information regarding the 22 missing vessels that should be being built in the Japanese shipyard.

Things did not flow as planned with the recently acquired Japanese tankers. One year and two months after its welcoming ceremony at the Venezuelan port, the Yare tanker underwent emergency repairs after it damaged its hull on May 28, 2012. Reuters informed that the vessel was being repaired at a shipyard in the Bahamas. It remained in the dry dock of Freeport, Bahamas for three months. Although no oil was spilled, PDVSA was forced to charter other tankers to replace the Yare’s operation. Unofficial sources say that the tanker hit a sand bank near the terminal of the Bahamas Oil Refining Company (BORCO).

The amount PDVSA paid for each Japanese oil tanker does not match the prices that the foreign market had set for Aframax models at the time of purchase. A former officer at PDV Marina who asked to remain anonymous said: “The Venezuelan-flagged Tamanaco, Terepaima, Yare and Paramaconi, built at Japan’s Sumitomo shipyard were acquired by PDVSA Naval (with financing from PDV Marina) at an obscene overprice estimated at over $30 million for every one of them”. The source added that he found evidence of these irregularities during the first month of his tenure at the oil company. In a Board of Directors meeting, the officer requested a copy of the Japanese tankers sales agreement with the intention of verifying the actual price PDV Marina paid for them. He was never allowed access to this document which meant a radical change in his work relation with the president of the subsidiary, Asdrúbal Chávez.

He was certain that there had been a surcharge after ordering an investigation on these irregular actions. The former director met with Japanese representatives who offered him two oil tankers worth $87 million each with the same characteristics as those that had been constructed at the Sumitomo shipyard and at the same price that PDVSA had paid the year before. Inquiring quotes in the foreign market, he found an Arabian company that sold two vessels of the same year and model and built at the same shipyard which were worth $49 million. This is a little more than half of what the Japanese oil tankers cost Venezuela.

A similar example was found in an April 2010 report published by Ten Tsakos Energy Navigation (TEN) Ltd., one of the largest transporters of energy in the world. This report revealed that they expected the delivery of an Aframax built by Sumitomo Heavy Industries by July of that year. Its cost was said to be $60.7 million. This means that this company paid $26.3 million less than what PDVSA paid for each of the Japanese oil tankers in 2010.

Inquiries regarding these negotiations were made to Sumitomo Corporation de Venezuela in Caracas and Sumitomo Heavy Industries Ltd. in Japan. No reply was given as this report went to press. It must be said that the telephone numbers and public e-mails provided for the offices of this company in Caracas do not work. Its office is currently closed.

Fifteen years after signing the first agreement related to the Oil Sowing Plan and behind the fence of US sanctions, the Maduro Administration no longer waits for the 42 new oil tankers that would reinforce PDVSA’s fleet and would transport Venezuelan oil across the globe as originally planned. Until August 2020, PDVSA was producing 300,000 barrels of oil a day, 10 times less than what it had made in the last decade. Rafael Ramírez no longer lives in Venezuela and his relationship with Nicolás Maduro is non-existent. And yet he questions the government and the oil company’s drift. Taking no responsibility, he asks: where are the oil tankers?