During the pandemic, the peak of devastation in mining municipalities went up. In 2020, the largest tree cover loss was recorded in Bolívar state in the last two decades due to the expansion of mining. Rivers contaminated with mercury and toxic waste from cyanide plants and mills show that the demarcation of uses within protected areas and public policies to mitigate environmental impact are dead letters. Concepts such as sustainability, biodiversity conservation, and permanence of indigenous peoples contemplated in the Constitution of Venezuela are absent in the mining megaproject decreed by Maduro

Three men in flip-flops, wearing worn flannels and rolled-up pants walk along the side of the road that crosses the Sierra de Lema, the leafy preamble to the Gran Sabana that is part of the Canaima National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Like Vietnamese hats or hanged on their backs, they carry the traditional wooden pans that they use to extract gold nuggets from the rivers. In theory, those artisanal miners should not work in a protected natural area where mining is legally prohibited. But the holes of earth and mud that begin to open in the dense forest evidence, like little red flags, the gold exploitation that exceeds the limits of the neighboring municipalities of the Arco Minero del Orinoco.

In January 2020, weeks before the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic in Venezuela, the landscape of devastation was just beginning to take shape along Troncal 10. At that time, some walls of companies under construction were erected without signs or billboards and a few meters from the road there were movements of land and felled trees, especially between the towns of Tumeremo and Kilómetro 88. Two years later, dozens of artisanal mills have been shamelessly installed to process gold with the use of mercury as well as industrial cyanidation plants to recover the metal extracted from the gold sands. Now people can see with the naked eye much of the environmental crusher promoted by the mining megaproject established by Nicolás Maduro.

The Sierra de Lema, which is part of the Canaima National Park, begins to suffer the ravages of illegal mining

The Sierra de Lema, which is part of the Canaima National Park, begins to suffer the ravages of illegal mining

In a matter of two years, Troncal 10 has become a main road in danger of extinction. Such is the deterioration of the road that crosses the municipalities of Roscio, El Callao and Sifontes that the asphalt pavement disappeared in some sections due to lack of maintenance but also due to the constant move of food containers from Brazil, and trucks that carry tons of gold material from mines and mills to cyanidation plants.

Precisely between El Dorado and Tumeremo, where the most cracked parts of the road stand out, and the largest number of mills and industrial leaching plants were settled, almost 80 thousand hectares of "wooded lots" were delimited two decades ago under Executive Decree number 2.214, published in the Official Gazette 4.418 of April 23, 1992. Although these legal forms established in the state of Bolívar are not recognized in the Ley Orgánica para la Planificación y Gestión de la Ordenación del Territorio (Organic Law for the Planning and Management of Territorial Arrangement), they must also be administered under the same regulations for the management of forestry activities because they correspond to a presidential decree, according to experts.

But the truth is that long before the creation of the Arco Minero in 2016, much of the forests of Bolívar state, among which are the jungle lots of El Dorado and Tumeremo as well as the Imataca Forest Reserve, have been subject to permanent pressures such as land use, agricultural activities and conflicts with gold mining. The historical absence of instruments for planning and ordering the territory as well as of surveillance and control led to the anarchic growth of illegal mining with its consequent environmental impacts, evaluate experts consulted.

From Troncal 10, the international highway that connects the mining municipalities, it is possible to observe the progress of deforestation due to illegal mining

From Troncal 10, the international highway that connects the mining municipalities, it is possible to observe the progress of deforestation due to illegal mining

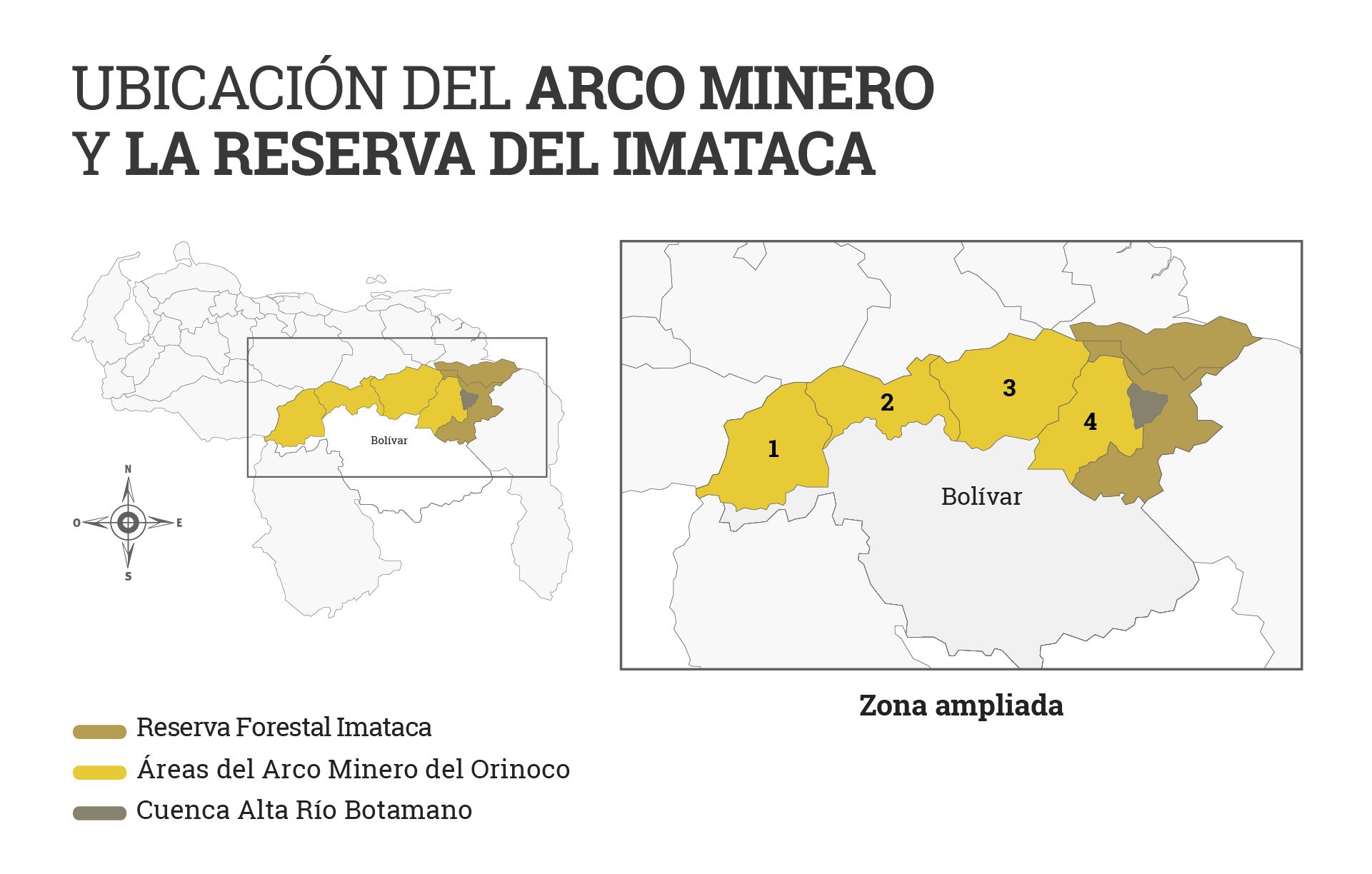

The delimitation of uses within areas under special administration regime (Abrae) that are in the polygonal of the Arco Minero del Orinoco has not been enough to stop mining. Such is the case of the Imataca Forest Reserve (RFI), a forest of 3.5 million hectares between the states of Delta Amacuro and Bolívar, a biodiversity refuge where at least six indigenous peoples coexist: Pemón, Kariña, Warao, Arawak and Akawaio. Subjected to strong extraction pressures, it is located in Area 4 of the mining belt, intended for the exploitation of gold and coltan.

With the decree 3.110 signed by Hugo Chávez in 2004 was established the Plan of Arrangement and Regulation of Use (Plan de Ordenamiento y Reglamento de Uso - PORU) of the Imataca Forest Reserve for the use of natural resources under the principle of "sustainability, conservation of the biodiversity, permanence of indigenous peoples, protection of socio-cultural values, security and defense of the nation". Along with allowing mining use in some areas, the PORU of the RFI also contemplates "recovery areas" to contain mining activity. “But this regulation is not being followed. All mining projects must include recovery programs. Although the ecosystem cannot be fully restored, it is possible to return part of the vegetation cover with a certain number of species," says Vilisa Morón, president of the Venezuelan Society of Ecology.

"The fact that the government has demarcated the entire strategic area of the Arco Minero and defined the areas and minerals to be exploited does not imply that it can do anything there. All mining operations must contemplate measures to mitigate the environmental impact following the Organic Law of the Environment, a task for which the Ministry of Ecosocialism must oversee as authority in the matter," says Morón. The biologist emphasizes that there are not known management programs of the forest reserve or what the compensations of the mining activity will be. There was also no prior consultation with the indigenous peoples present in the mining territories as established by the Constitution.

Mining camps are shamelessly installed on the banks of Troncal 10

Mining camps are shamelessly installed on the banks of Troncal 10

Public policies of environmental protection are among the great mysteries of the Arco Minero. There is no known comptrollership on these processes, nor exploration investment plans. The Ministry of Eco-Mining Development has announced that there are about 50 environmental impact studies, a figure that is questioned by all the specialists interviewed for this research: "if they exist, they could be forged".

In 2018, the Strategic Office for Monitoring and Evaluation of Public Policies of the Office of the Vice Ministry of Exploration and Ecomining Investment, attached to the Ministry of Eco-Mining Development, announced that 1,048 brigade members and environmental guardians were added. Alliances with artisanal mining must have at least two environmental guardians for the detection of illegal mining activities and promote measures to mitigate impacts and environmental recovery. The follow-up of this measure is not known. Neither Minec nor Mindeminec have reported it since.

The militarization of the deposits in the state of Bolívar goes beyond the presence of soldiers along Troncal 10, in which there are more than 20 checkpoints and ''alcabalas'' between Upata in the Piar municipality and Kilómetro 88 in Sifontes. This process is related to the very conception of the Arco Minero del Orinoco. Lawyer Enrique Prieto Silva, professor of ecological law at USM, questions the incorporation of the national armed forces in gold exploitation because it contradicts the essence of the institution. Both the creation of the Military Limited Company for the Mining, Oil and Gas Industries (Compañía Anónima Militar para las Industrias Mineras, Petrolíferas y de Gas - Caminpeg) in 2016 and the participation of the National Guard distort the role of custody and surveillance of nature and sovereignty.

Article 100 of the Organic Law of the Environment (2006) establishes that the environmental care, understood as the monitoring and control of activities affecting the environment and the requirement of compliance with measures for the conservation of a healthy, safe and ecologically balanced environment, must be exercised by the Armed Forces represented by the National Guard, in addition to other ministries with competence in environmental matters. While article 101 states that the officials of the environmental patrol are entitled to act in case of the perpetration of an environmental punishable act, or an administrative infraction. "But instead of being environmental guards, in the Arco Minero they act as political police," affirms Prieto Silva.

Chaos and control

The non-existent surveillance of the rule in mining also explains the causes of the environmental devastation. A geologist consulted in Ciudad Guayana for this investigation, who asked not to be named, estimates that between 95% and 99% of mining projects, which include excavations in alluvial or vein mines, processing in mills, and cyanidation plants, have not complied with the corresponding previous studies.

"It happens in the world of mining: if you don't have a well-formulated initial plan, you go straight to failure. You end up doing survival mining, destroying the environment, and the future of your children and grandchildren," sustains the geologist interviewed with the property of who has participated in around twenty exploration studies within the Arco Minero.

According to the expert, every mining project must follow the following steps: preliminary bibliographic research; prospecting (taking geochemical samples in the field that will then be analyzed in the laboratory); exploration (field inspection to locate areas where there is economically profitable mineral presence); analysis of the feasibility of the project (cost calculation); project design; and construction.

The mentioned stages describe what should be, precisely what is not complied in the Arco Minero del Orinoco, the specialist analyzes. "The mining business is a very expensive and high-risk project. In the first place, you must necessarily have a good investment capital. A serious geological study, including the initial phases of prospecting and exploration, can take three to five years. From the fifth year and not earlier is when the investment begins to reverse". He gives as an example the exploration phase of the company Barrick Pueblo Viejo, of the Barrick Gold Corporation group, in a mine in Santo Domingo, which took about eight years investing at a loss.

Regarding the mining megaproject in the south of the country that occupies approximately 12% of the national territory –although it affects 40%, highlights the director of Clima 21, Alejandro Alvarez– the prospecting and exploration studies that any mining project must contemplate are unknown. "What is happening is that they open more and more holes without previous studies, creating open-pit mines with uncertain exploitation. I dare to say that 95% of the projects in the Arco Minero respond to a pattern of chaos and disorder. In any ravine (shaft mines) you see a disaster. A crowd, the one who charges the bribes on one hand, the one who is watching who takes gold or not, the child who begs."

This situation is aggravated by the fact that deposits of gold sands accumulated during the last decades are being exhausted. The need to produce raw materials to be processed in cyanide plants promotes uncontrolled excavations, soil movements, soil erosion, and water pollution by the use of mercury and river sedimentation. Without prior geological studies, it is an unsustainable operation with which there is no guarantee of finding gold in those lands.

In a recent report, the SOS Orinoco organization sustains that cyanidation plants are not complying with their initial goal of becoming more profitable and less polluting. The largest production in the Arco Minero continues to come from open-cast and vertical mines, from the work of artisanal miners, and not from industrial leachate plants.

Waters intoxicated by gold

Eager to find some metallic shine, a group of naked-chest young men dive into the Yuruari River that borders the mythical town of El Callao in the Bolívar state. They are guided by wooden tripods that, in a rudimentary way, mark the height on the thick waters due to the sedimentation produced by gold exploitation. The boys seem to ignore an old legend: every so often, the Yuruari, enraged by so many years of mining pollution, goes out of its channel, taking with it anyone who approaches its banks.

The gold rush also stirs up the fragile riverbeds. From the emblematic bridge falsely attributed to Gustave Eiffel over Troncal 10, in El Dorado, a couple of mining rafts extract gold from the bottom of its opaque waters.

Mining raft on the Cuyuní river that borders the town of El Dorado

Mining raft on the Cuyuní river that borders the town of El Dorado

The contamination of the Cuyuní and Yuruari rivers due to gold activity in southern Venezuela is an already sedimented threat. Morón explains that the change in the physicochemical properties of these water sources is due to the fact that the waste from cyanide plants, mines and mills as well as the earth removed by mining are thrown into the river, affecting the ecological dynamics associated to the banks. "Water is no longer drinkable for communities," the biologist observes.

A study published in 2009 on the geochemistry of the aquatic ecosystems of the upper basin of the Cuyuní River found the highest levels of phosphorus and nitrates in the lower Cuyuní River, behavior that researchers indicate may be associated with pollution. The research explains that the waste from mining operations is discharged directly into the rivers, which significantly affects the geochemical characteristics of the waters and favors the accumulation of sediments and the increase of the turbidity of the waters. "This, in turn, destroys benthic ecosystems (of the aquatic bottom) and substantially limits visibility in the water affecting fish, birds and mammals that depend on these bodies of water".

They emphasize that the alteration of the geochemical properties of the waters produces possible long-term modifications of the course of the rivers, in addition to the fact that the discharges of substances such as mercury, fuels, lubricants and waste are distributed downstream, causing the impact of the activity to transcend “beyond the confines of the mines”.

Where there were trees and grasses, mills and cyanidation plants are now installed for the processing of gold sands

Where there were trees and grasses, mills and cyanidation plants are now installed for the processing of gold sands

The mayor of El Callao, Coromoto Lugo, who has held the position in four non-consecutive periods, confirms that the environmental impact of the Arco Minero has been very harmful to the population. "It provides the government with many resources but does not translate into social welfare. El Callao is a very rich and very poor people at the same time, especially in terms of basic services."

Lugo highlights as one of the most serious consequences of the Arco Minero the high pollution of the Yuruari river and the water treatment plant does not have the equipment to ensure that the water they receive in El Callao complies with the chemical parameters. "We have not had drinkable water for four years. The latest information we have is that due to the high contamination of the Yuruari, no more water can be pumped from the river to the reservoir. We are forced to extract water for the community from a reservoir that was built years ago by the Canadian Crystallex, an expropriated mine. That water is even healthier than the river itself."

"We have already lost the river," says Lugo about the main (and only) water source of El Callao. According to studies by Hidrobolívar, the Red Cross, and professionals from the municipality of El Callao, the water from the Yuruari cannot be used, he says. "It’s worrying. Some companies take water from the river, others have built tanks. Mercury contamination has not been specifically measured in the region but levels are high. The last study was done by UCV 10 years ago."

On the way to the Gran Sabana in the Canaima National Park, checkpoints of mining points, improvised garbage dumps, and mining camps are installed

On the way to the Gran Sabana in the Canaima National Park, checkpoints of mining points, improvised garbage dumps, and mining camps are installed

In January 2022, Coromoto Lugo issued Decree No. 4 that prohibits the passage of trucks to the center of El Callao, due to the damage they cause on the road by transporting up to 50 tons of material. They use the same road corridor built by Minerven 30 years ago for this type of truck. Although they continue to circulate without canvas to cover the material, they are no longer entering El Callao but instead use the substitute corridor of Nacupay. But still, the dust and mud they leave behind is remarkable. Just by looking at the state of Nacupay, La Ramona and Perú it is possible to evaluate the investment of the plants in the mines of El Callao.

It is no longer just about pollution in rivers and soils. Mercury also poisons the air in mining areas. There is evidence of atmospheric mercury contamination. A 2012 study by chemist researcher Nereida Carrión evidenced that school children in El Callao near the mills had high concentrations of atmospheric mercury.

In a presentation at the UCAB Guayana in 2019, Carrión said that 74% of the schools in which the concentration of mercury in the air of the classrooms was analyzed had levels above the allowed reference value. "And the highest concentrations of mercury were found in schools that have mills nearby, that is, there is a significant correlation between the levels of mercury in urine and in blood, and the distance from the child's home to the mills, so this emission source affects mercury levels in children," she said.

Another study showed that 41% of the population in downtown El Callao had higher than tolerable urine mercury values. Carrión then explained that this could be associated with an increased exposure with the gold shops, where the metal is heated, and in that process mercury vapors are expelled continuously. The children of a school in the downtown showed higher levels of concentration compared to other schools, "but it is not only them, but also the other people who spend 4 to 6 hours a day in that school."

Although there is no updated research, it is possible to infer that the situation may be even more serious considering the proliferation of artisanal mills in the Arco Minero in the last two years.

Less green

One of the most serious impacts left by mining is deforestation. Venezuela is the Amazon country with the highest deforestation trend. The nation lost 1,130 square miles of Amazon forests between 2001 and 2020, according to the Amazon Network of Georeferenced Socio-Environmental Information (Red Amazónica de Información Socioambiental Georreferenciada - Raisg).

On the other hand, Provita's "Coverage and land use in the Amazon" study identifies 2,800 square kilometers of forest loss due to deforestation in the Venezuelan Amazon, equivalent to almost three times the size of Margarita Island.

Mining and agricultural activity are the main causes of forest loss, but the organization has highlighted that in the last two decades the extension of mining in the south of the country has almost doubled. The municipalities with the largest mining areas in Bolívar are Angostura and Gran Sabana, and Sifontes. In the latter, mining escalation has been from around 50 square kilometers in 2008 to 160 km2 in 2020, three times as much, according to Provita.

Open pit mine in Las Claritas. Artisanal miners live with their families on these gold deposits under the control of armed groups known as mining unions or "the system."

Open pit mine in Las Claritas. Artisanal miners live with their families on these gold deposits under the control of armed groups known as mining unions or "the system."

The pandemic did not stop the deterioration of primary forests and the loss of tree cover in southern Venezuela. The Global Forest Watch satellite monitoring platform states that from 2016 when the AMO was officially created until 2021, Bolívar lost 108,000 hectares of primary humid forest. The two biggest loss years have been 2019 and 2020. This occurs at a time when the jungles of the Amazon are losing resilience and approaching a tipping point.

In this six-year period, the tree cover loss in Bolívar reached 173 thousand hectares. But GFW figures show that in 2020, the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown, cover loss –defined as all vegetation over five meters tall– was higher than the previous year. In retrospect, it has been the largest in the last two decades.

In 2019, 36 thousand hectares of tree cover were lost in Bolívar, while in 2020 the loss reached over 37 thousand hectares. In 2021, however, the decrease is around 14 thousand hectares, equivalent to 8.31 million tons of CO₂ emissions, according to the satellite monitoring platform.

20% of the loss of vegetation since the creation of the Arco Minero is associated with fires.

The tree cover loss dataset, which considers not only anthropic but also natural causes, is a collaboration of the University of Maryland, Google, USGS and NASA, and uses Landsat satellite imagery to map annual tree cover loss with a resolution of 30x30 meters.

The disturbance of the Amazon rainforests by increasing deforestation and fires affects the capacity to absorb carbon dioxide and, therefore, favors global warming. What happens in the Arco Minero del Orinoco contributes to the disturbances of the largest tropical forest in the world.

Contaminated lagoons and neighborhoods gain ground in the open pit mines in Las Claritas

Contaminated lagoons and neighborhoods gain ground in the open pit mines in Las Claritas

Between 2001 and 2021, an annual average of 12.1 million tons of greenhouse gases were emitted into the atmosphere as a result of the tree cover loss in Bolívar. But GFW figures show that in 2020 there was a peak and emission of 21.7 Mt of CO₂ equivalent “in areas where the dominant factors of loss resulted in deforestation” for shifting agriculture and associated with raw materials.

“The degradation of the forests in the Arco Minero goes beyond the green area cleared. It also affects the diversity of the fauna and the microclimate of the place,” affirms the biologist Morón.