During the COVID-19 pandemic, the destruction of the mining megaproject, boosted by Nicolás Maduro in the south of the country for the exploitation of gold and other strategic minerals as a financial alternative to the ruined oil industry, increased.

In a trip of more than 800 kilometers through four mining municipalities of the Bolívar state, at least 41 joint ventures and alliances between private and State were identified, which are part of the corporation responsible for the mining devastation in a territory controlled by organized criminal gangs in coexistence with military forces and guerrilla groups.

The ineffectiveness and improvisation in the auriferous production chain propitiate a greater environmental disaster in the Venezuelan Amazon

Esta investigación la encuentra en español gracias al apoyo de nuestros lectores y clientes, y se puede visitar haciendo click en este enlace

Lisseth Boon, María Ramírez Cabello and Lorena Meléndez

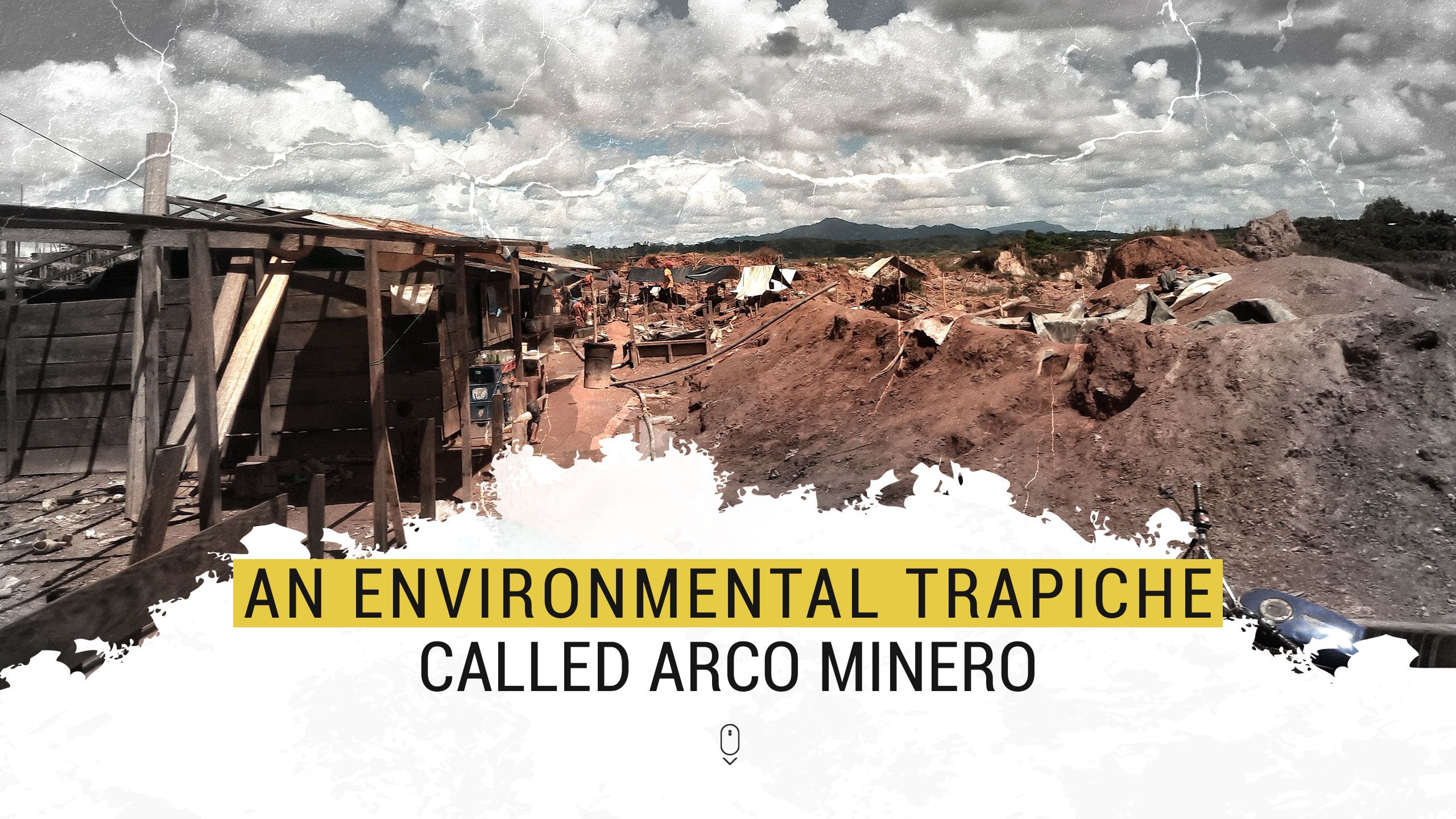

A pair of dying light bulbs illuminate the rattle of an artisanal mill in the middle of the night. Three men without helmets or gloves operate the machines that process a batch of soil loaded with gold a few meters from Troncal 10, the route that connects the main towns of the Arco Minero del Orinoco (Orinoco Mining Arc), south of Bolívar state in Venezuela. Near the small rustic structure, the towers of an industrial gold cyanidation plant illuminated by powerful reflectors stand out. But between its high silos there is no movement of trucks or workers.

At dawn the colors of mining devastation explode. Along the main road artery of the Arco Minero del Orinoco, on land where there were once trees and grasses, there are now swamps, holes, and puddles. Signboards and walls with signs of unknown companies swarm at the same time as new cyanidation plants and artisanal mills are installed to process gold. The Yuruari and Cuyuní rivers, which surround the mining towns, became channels of clay sediments. Children and teenagers ask passers-by for tips to fix the road that completely lost the asphalt in some of its sections. On the deteriorated route, containers with food from Brazil and trucks transporting tons of auriferous sands to the industrial complexes, leave in the air a thick mist that makes it difficult to breathe.

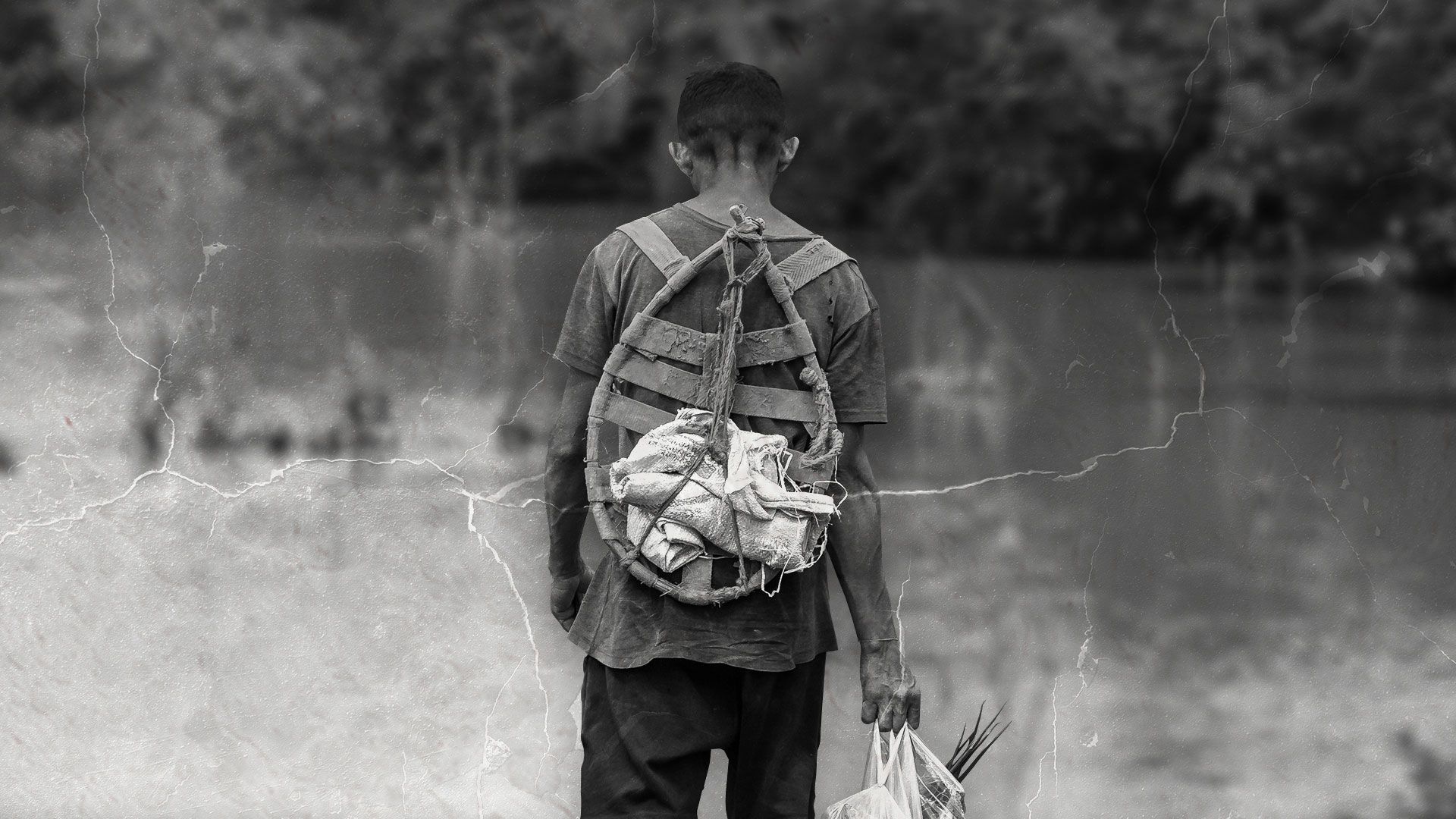

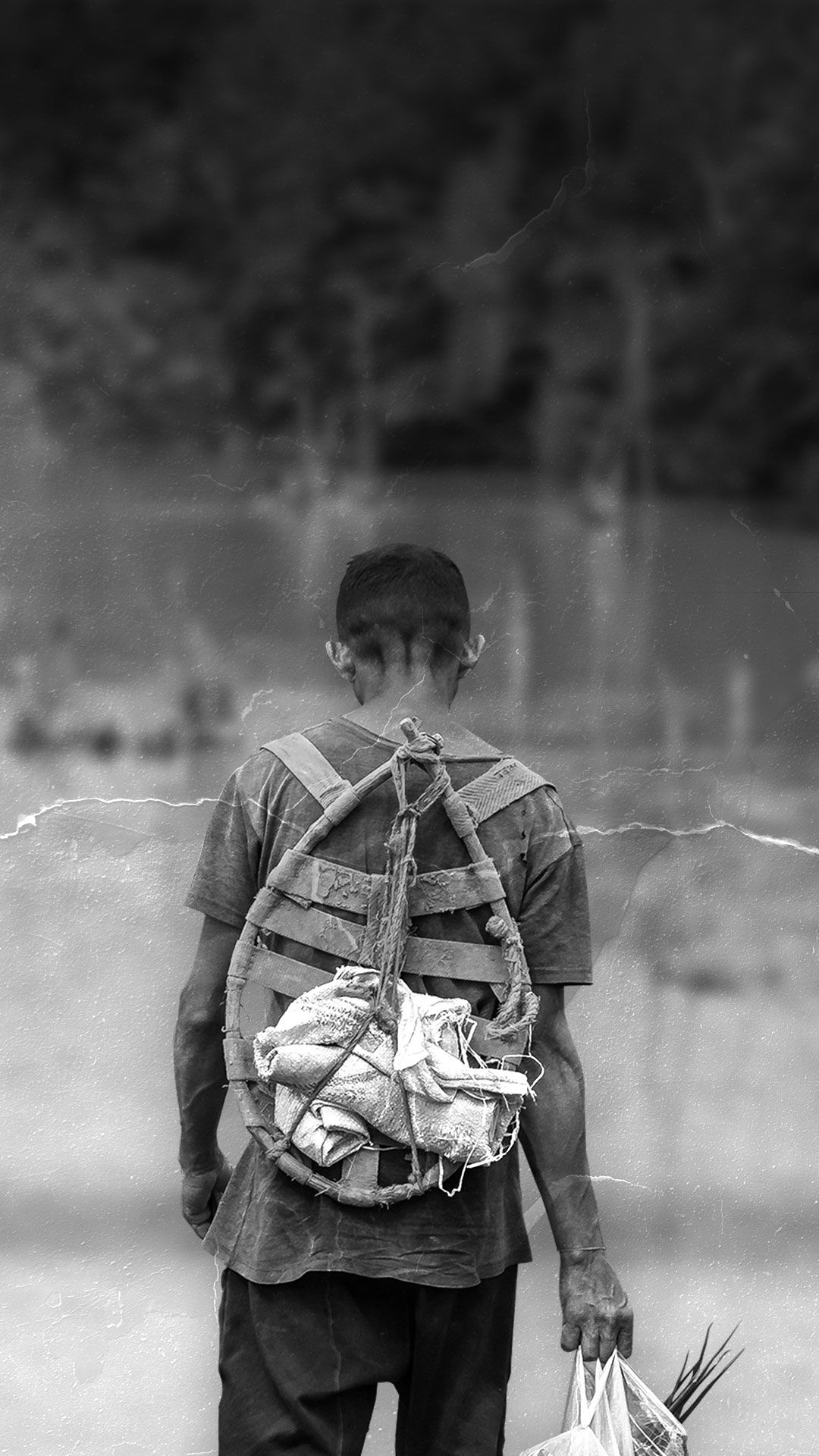

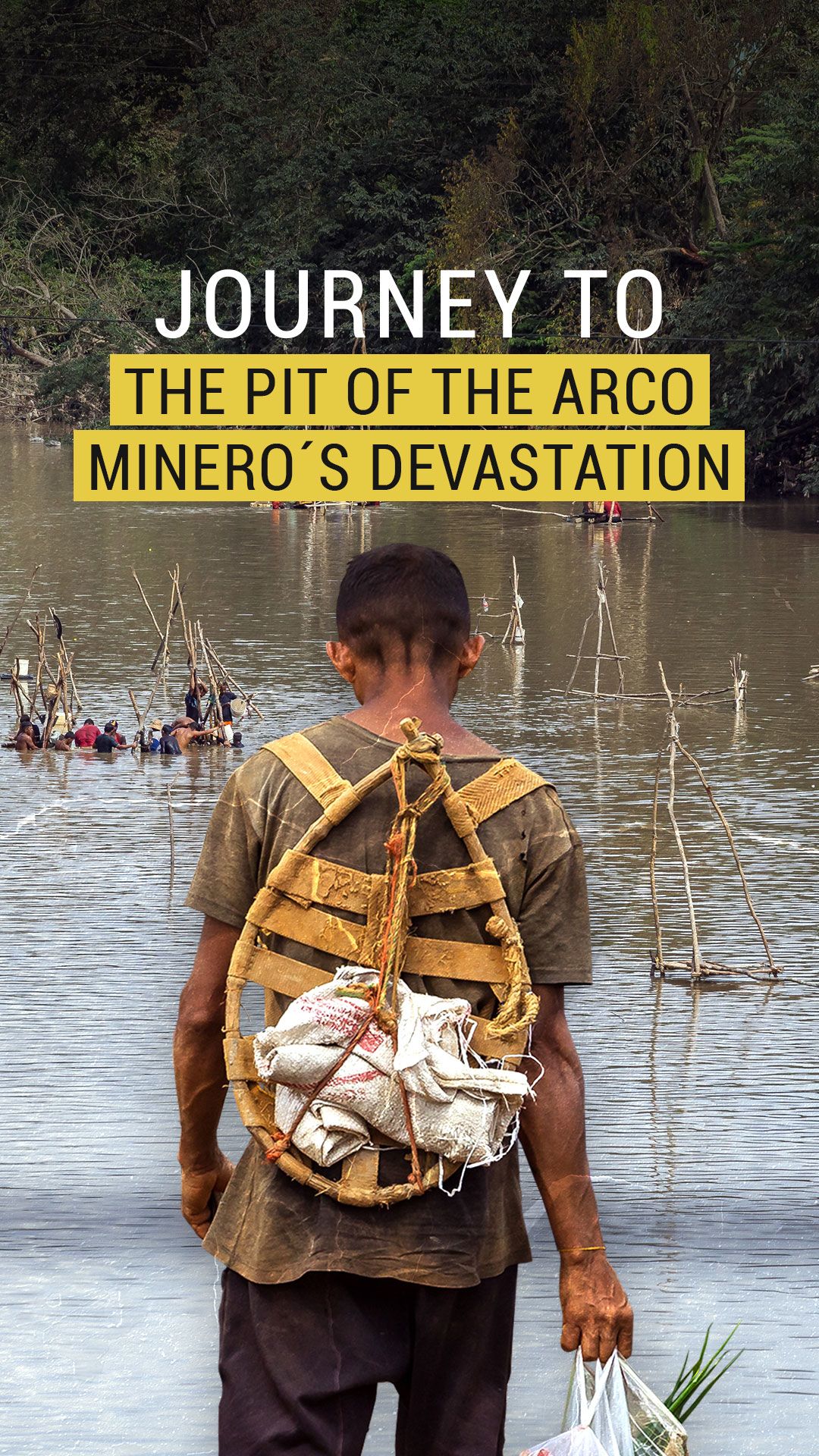

Artisanal miners, carrying wooden trays on their backs to sift the golden metal, walk along the roadside to some gully or open-pit mine under the control of criminal gangs known in the region as “sindicatos” (syndicates) or “sistemas” (systems). Rows of shacks made of plastic and fiberboard walls, selling everything from chewy empanadas, gasoline in plastic soda bottles to minutes of satellite internet in a region without connection or local telephone service, are added to the growing makeshift villages that spread across the landscape.

The pandemic did not stop the destruction in the Arco Minero del Orinoco, but rather deepened it. Through a route of 850 kilometers along Troncal 10, which crosses Roscio, El Callao and Sifontes municipalities of the Bolivar state, the team of journalists from Runrun.es and Correo del Caroní verified directly the impact of gold mining activity in the region after 24 months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Far from reducing mining exploitation, during a quarantine marked by intermittent mobility restrictions, and an acute fuel shortages in the region, the consequences of the chaotic extractivist policy worsened with respect to the previous coverage registered in January 2020.

Artisanal miners work in open pit mines in Las Claritas, Sifontes municipality

Artisanal miners work in open pit mines in Las Claritas, Sifontes municipality

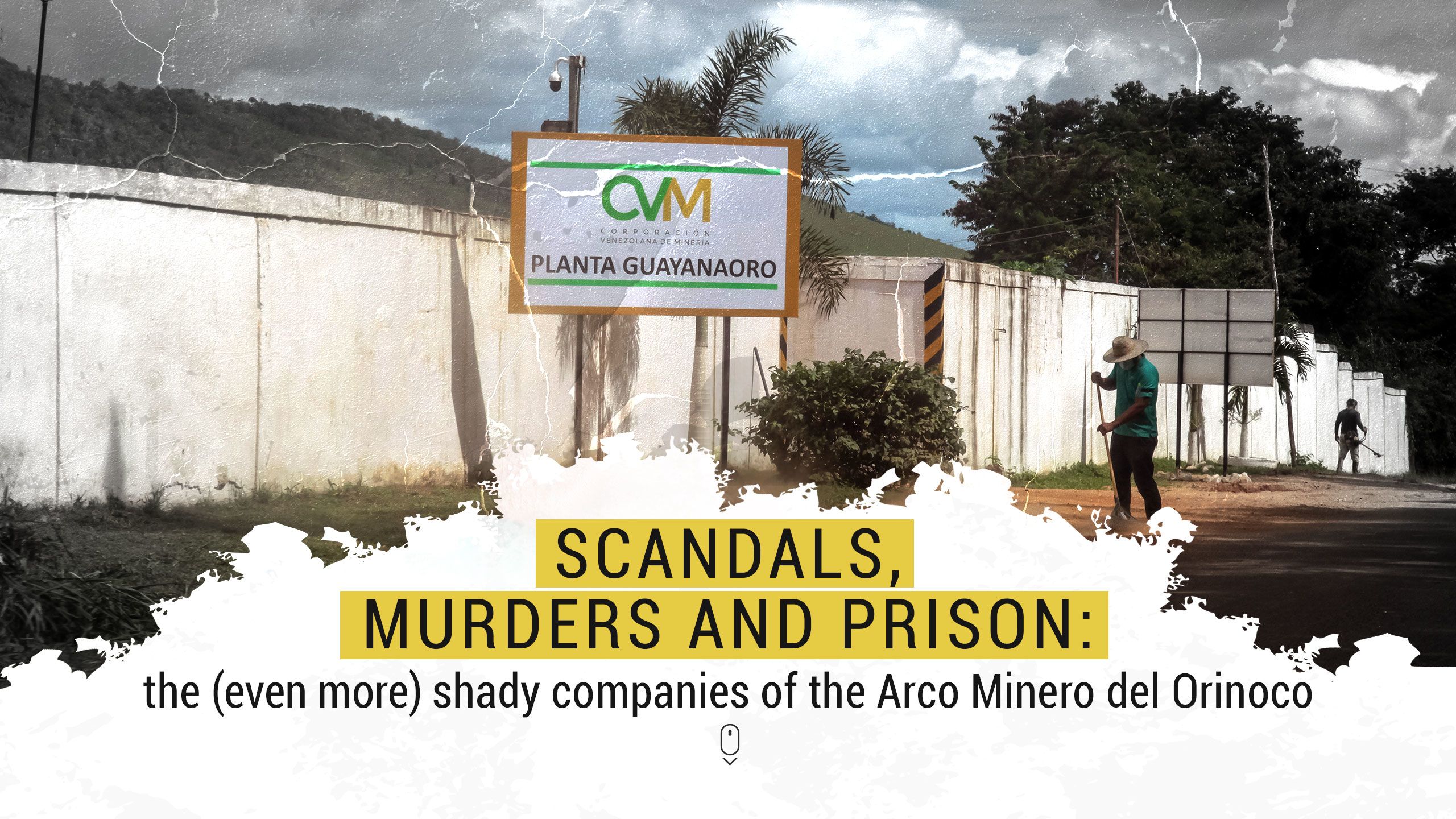

The most visible sign of the advancement of the mining megaproject decreed by Nicolás Maduro in 2016 and which occupies 111,846 kilometers, almost 12% of the national territory, is the appearance of companies and industrial plants (public and private) on the roadside, whose productive performance is kept under official secrecy. The facilities, with large walls and signs with their names labeled, began to be erected in the midst of the pandemic.

Of the 41 companies identified in the misleading corporate map of the Arco Minero del Orinoco, the management of the two largest industrial complexes has been linked to the presidential family or public officials; of 75 percent of the total (31 of 41) the public procurement process is unknown: whether they were assigned by hand or were presented in official competitions. Just six are registered and authorized to contract with the State. It is not certain how many of them remain operational and none of them gives a public account of their productive performance.

Official billboard at Kilometro 88 - Las Claritas showing the chain of command of the PSUV in the Mining Arc

Official billboard at Kilometro 88 - Las Claritas showing the chain of command of the PSUV in the Mining Arc

The production figures as well as those of trafficking of gold extracted from the Arco Minero continue in opacity. It is not known for certain how much gold is being taken out of the mining megaproject created by decree in 2016, or how much is being smuggled. Based on the calculations of the organization Transparencia Venezuela, the production of the Arco Minero is around 25-35 tons per year, of which it is estimated that 70% comes out as "dispersed flows", as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) categorized the informal and illegal gold trading channels.

It is a latent social outbreak the conflict between the indigenous communities within the Arco Minero and the criminal gangs called “colectivos”, mining unions, or ”el sistema" led by “pranes” (prison or gang bosses), who have consolidated territorial control of the mines with the consent of the State. The most recent evidence of this dispute over the exploitation of gold within the indigenous territory took place in the second week of January 2022, when local leaders decided to block the passage for 10 days through Troncal 10, the main road artery of the mining belt, which caused supply problems. The tension was dismantled after meetings with local authorities, the regional government and the Corporación Venezolana de Minería (CVM), the coordinating body for management within the Arco Minero.

Artisanal miners gather in the Plaza Bolívar in El Callao and then move on foot to the nearby mines

Artisanal miners gather in the Plaza Bolívar in El Callao and then move on foot to the nearby mines

In two years of the pandemic, the scheme of the “pranato” in the mine control has been consolidated, characterized by the territorial dominion and coexistence agreements between criminal gangs and the State, which includes security forces (Army, National Guard and regional police) as well as demobilized armed groups (ELN and FARC) that provide surveillance service to joint ventures and industrial gold cyanidation plants that are part of the strategic alliances between the State and private companies.

The gold rush has also reshaped the lives of mining populations. The proliferation of slums along the road and in some historic mining towns was observed during the tour of Guasipati, El Callao, Tumeremo, El Dorado, Las Claritas and Kilómetro 88 as well as the borders of the Gran Sabana (which houses the Canaima National Park) and the San Miguel de Betania indigenous community. The appearance of houses with zinc roofs and walls of wooden boards and plastic bags, are evidence of the demographic explosion in the Arco Minero and the growth of poverty with the consequent collapse of already precarious public services. They are also a sign that the Arco Minero did not arrive accompanied by social policies to benefit the communities of the mining towns or articulate measures with local governments.

The wealth of the Mining Arc is not reflected in the mining communities that suffer from the collapse of services and precarious infrastructure

The wealth of the Mining Arc is not reflected in the mining communities that suffer from the collapse of services and precarious infrastructure

The team of reporters interviewed about twenty people, including regional authorities, representatives of the trade, gold mining and jewelry union, teachers, indigenous leaders, sociologists and artisanal miners. They requested information from the CVM attached to the Ministry of Ecological Mining Development and the Ministry of Ecosocialism without obtaining a response. They also consulted experts in human rights, ecology and environment, in Puerto Ordaz and Caracas. A multiplicity of voices contributed to putting together the portrait of the new landscape in the Arco Minero del Orinoco that broadens the pit of destruction in the Venezuelan Amazon.

The six stops along the way

Texts and research

Lisseth Boon, María Ramírez y Lorena Meléndez

Graphic concept and infographics

Runrun.es

Illustrations and infographic

Gabriela Lara

Development and web design

Abrahan David Moncada

Photos and videos

William Urdaneta

Videography

Abrahan David Moncada

Editing and texts correction

Luis Ernesto Blanco and Lorena Meléndez

Social media strategy

Luis Miquilena, Ricardo Machado and Joelnix Boada

General coordination

Lisseth Boon

Direction

Nelson Eduardo Bocaranda

Published in spanish on September 18, 2022.

Translated and republished on January, 2023.