Deep in the Arco Minero del Orinoco, gold shines only for a few. Most of those attracted by the golden promise suffer the severity of slave labor, the violence of armed groups and the constant interruption or total absence of public services such as electricity and water, whose deterioration has been accentuated by overpopulation. The main road has been destroyed by the constant move of trucks, but –even with the difficulties of access– makeshift camps and invasions make their way after the felling of trees in the Venezuelan Amazon.

In the center of El Dorado, rudimentary constructions of homes and business shops line what looks like a super highway designed for a big city. But it only seems so because of the width of the road, in which four vehicle circulation channels would perfectly fit. The stretch of land and lunar holes is a constant dusty cloud, due to the traffic of cars and motorcycles. The space was the runway of the airport of the mining town, in the municipality of Sifontes, but the demographic explosion generated by the exploitation of gold in the Arco Minero del Orinoco turned it into an invasion, one of the dozens that have been installed fast in the last two years in points as unusual as an airstrip as well as in the middle of the jungle.

"Here was the airtrack and on the sides there were green areas, but they invaded it. Government and company planes landed there. Even 'la vaca sagrada' arrived, the plane that brought the prisoners to El Dorado jail, near the town. The government says it is going to recover it, but they are already large constructions," said a resident of the mining town, who asked not to be named for safety. The invasion began four years ago, they estimate, and has only been growing. Satellite images from Google Earth Pro show the disappearance of green lines on the edges of the airport.

After former President Hugo Chávez nationalized the gold industry in 2011 and his successor Nicolás Maduro created the Arco Minero del Orinoco five years later, the arrival of workers in southern Venezuela did not stop. Although the goal of the Arco Minero was to reorganize mining extraction and invite multinationals to explore one of the largest gold deposits in the world, the collapse of the economy made the hot gold deposits a fertile soil for the arrival of labor from all over the country.

Migration occurred even from nearby population centers such as Ciudad Guayana, the main city in southern Venezuela, conceived as the country's non-oil economic alternative. The productive collapse of the metal industries located on the southern bank of the Orinoco River, led workers —before with enviable wages and contractual benefits— to migrate to the mines in search of economic sustenance.

With that objective, hundreds of people from near and distant regions arrived in search of the enigmatic “dorado”: men, women and children. Even professionals willing to leave their university careers to dig in the ground. But the mining areas were not prepared for such an avalanche. Socioeconomic studies such as the National Survey of Living Conditions (Encuesta Nacional de Condiciones de Vida - Encovi), which has the most up-to-date analysis differentiated by states, showed in 2020 that mining municipalities have the worst indicators in terms of poverty, nutrition, health, and access to public services in Bolívar. Sifontes is the municipality with the worst living conditions in Bolívar with indexes in the "very bad" range; 81.6% of its population lives in moderate and severe food insecurity.

The constant passage of trucks with food from Brazil and trucks transporting tons of cyanide sands have further deteriorated Troncal 10, the main road artery of the Mining Arc.

The constant passage of trucks with food from Brazil and trucks transporting tons of cyanide sands have further deteriorated Troncal 10, the main road artery of the Mining Arc.

One of the manifestations of the wave, although not the only one, is the illegal occupation of land that is repeated throughout the south of the Bolívar state, the largest in the Venezuelan Amazon. The population explosion was unstoppable during the COVID-19 pandemic. Compared to the beginning of 2020, months before the declaration of a pandemic, the felling of trees for construction is more evident and in those gaps in the middle of the Amazonian green cover, it is common for the view to collide with sectioned trunks and invaders that built barracks in a bad way with sticks and plastic roofs. It is evident along Troncal 10, which connects Venezuela with Brazil; in indigenous communities such as San Antonio de Roscio, whose center has been invaded by commercial stalls controlled by armed groups, and in the mining labyrinth in the depths of Las Claritas where the barracks rise uncontrollably near large mud-colored sinkholes where they exploit gold day and night.

At the back of the Fe y Alegría school in El Dorado, the land that was planned for an agricultural technical school was invaded seven years ago. "The predominant economic source in El Dorado has always been mining, but due to the country situation and the economic crisis, it was populated, populated, populated and filled with invasions," explained a teacher of the institution, whose name is kept confidential for security.

Willing to work in the gold deposits in El Dorado, dozens of people from all over the country invaded a field belonging to the Fe y Alegría school, where the construction of a technical agricultural school was planned.

Willing to work in the gold deposits in El Dorado, dozens of people from all over the country invaded a field belonging to the Fe y Alegría school, where the construction of a technical agricultural school was planned.

In the school, the demand for places has had unusual peaks due to the arrival of foreigners who come to join the mining troops. Most of the grades were filled this year. The new miners work in the Payapal and Los Arenales mines or in Panamá and Mochila, which are reached by river. In this last mine alone, six hours away by boat from El Dorado, there are 140 children without studying, according to the census of the communal council.

The increase of population in localities where government management is almost absent has meant the collapse of already deteriorating public services. At the beginning of the year, they spent up to four days without electricity in El Dorado and there are residential areas where they have up to three years without water service by pipes. "The electrical installations are obsolete. The invaders get connected to the lines and burn the transformers."

An overpopulated mining enclave

Lisbeth Lara, a 37-year-old from Apure, sells coffee in El Callao's Plaza Bolívar. In her homeland, she worked as a cashier in a grocery store, but two years ago she decided to travel to the mines to work and send money to her family. She started as a cook in a site near the village, but soon saw that life there was not as "easy" as she was told. "It's hard work, with virtually no schedules. I earn more than before, but you live very badly too. It has given me malaria like three times. It is a sacrifice. A lot of people come, try, leave and don't come back," she says.

Others remain. "There are too many people who come for survival, looking for a gramita (one gram of gold), a little money to survive, but they are entire families," affirms a social activist from Guasipati, in the Roscio municipality, who has seen the operations of donation of soups to low-income people grow from a pot for 30 people to 14 pots for two thousand people in the middle of the pandemic.

A worker of a state-owned aluminum company in Ciudad Guayana, with 20 years of experience in the industry, has compensated the deterioration of his salary with intermittent jobs in mining companies in the municipalities of El Callao and Sifontes. “When collective contracts disappeared, wages became nothing. That's why I decided to work in the south, because several colleagues were already doing it,” he said. During the pandemic, the maintenance technician was not included in the state's contingency plan, so he was sent home with a base salary. "I wasn't going to stay at home doing nothing, so the same thing I did in the company I do now in a mining company," he said.

There is no precision of how many new inhabitants have arrived in the municipalities of southern Bolivar in recent years. But at least in El Callao, a neighboring municipality of Sifontes, the current population is far from official estimates. According to the 2011 census of the National Institute of Statistics (Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas - INE), the last one that was conducted in Venezuela, the local population is 22 thousand inhabitants.

However, according to the municipal authorities, the population reaches 80 thousand inhabitants distributed in traditional residential areas and at least 21 new invasions have occurred in the last four years, which implies 263% of population growth. The Nacupay sector, where the Domingo Sifontes gold processing complex stands, has the highest number of invasions. "Many people come from the center of the country that demand electricity, roads, housing, water, health, that the mayor's office cannot attend to. The government did not calculate the social impact that the Arco Minero brought to these municipalities. This has to be coordinated and planned and we have none of that. What there is here is a great social injustice, the impact is paid by us," said the mayor of El Callao, Coromoto Lugo, who has held the position for five non-consecutive terms.

Lugo assures that he cannot remain silent. That it would be irresponsible to look away from the crisis that the municipality is experiencing, despite the implicit risks that complaints can generate. “It is a great mining opening but it leaves nothing to the municipality. Everything for the outside, but there are no benefits here,” he added. "An unfair economy that does not translate into the social," said.

In the last four years, 21 new invasions have risen in El Callao. Overcrowding has overburdened the deficient electrical system and deepened the crisis of public services

In the last four years, 21 new invasions have risen in El Callao. Overcrowding has overburdened the deficient electrical system and deepened the crisis of public services

It is hard to believe how a municipality like El Callao, with 39 gold processing plants, 1,200 mills and 600 gold purchases, according to a local census, suffers from the collapse of its services. But it happens. The streets both inside and the ones that lead to other nearby municipalities are destroyed. The hospital lacks specialists. There is no treatment of the water consumed by the population, nor water supply by pipes, and when power fails, only the large processing plants are lit up like fireflies in the middle of the night.

Lugo specifies that of the 40 thousand hectares that the municipality has, 38 thousand were handed over in 2018 to the Venezuelan Mining Corporation (Corporación Venezolana de Minería - CVM) for exploitation. It happened during the previous government administration. He estimates that roughly 3,000 kilos of gold leave the municipality per month. He is not opposed to mining, since he maintains that this is the main economic activity of southern Bolivar, but asks that the operations be coordinated with the local authority and generate benefits for the population.

"The CVM is obliged to create a Social Fund, to take care of the environmental impact and improve services and we have not seen that," he said. The mining industries consign 35% of their production to the CVM and 5% should be contributed to the Social Fund for works in the municipality, he specified.

The Venezuelan Mining Corporation (CVM) isn't accountable regarding the Mining Social Fund created for the social development of the towns close to extractive operations. Swipe and see the complete photo gallery

The creation of the Fondo Social Minero (Social Mining Fund) is established in Decree No. 2.165 with the Rank, Value and Force of Organic Law that Reserves to the State the Activities of Exploration and Exploitation of Gold and other Strategic Minerals, published in the Extraordinary Official Gazette No. 6.210 of December 30, 2015. The objective, indicates Article 42, is to guarantee resources for the social development of the communities surrounding mining operations.

"We are working in different areas to ensure the good living of the mining town, especially in the area of health, education; that is why we have recently created the Social Mining Fund," said the then Minister of Eco-Mining Development, Víctor Cano, in December 2017. “So that the life of the miners be dignified, so that we can build houses, schools, CDI (outpatient clinics), university villages, roads, we are beginning to call the mining entrepreneurs, but the organized miners also have to contribute, who will be the ones who will tell their true needs," said five months earlier Jorge Arreaza, who preceded him in office, during the announcement of the fund.

But after six years of publication of the decree, there is no public information on the income of the Social Fund from state operations, joint ventures and strategic alliances.

The "boom" that corrupted the local daily life

The mining activity has been carried out for decades in the municipalities of southern Bolívar. From the corporate point of view, the state-owned CVG Minerven took the reins of gold mining at least until 2011, although that did not prevent illegal operations from being maintained and expanded throughout southern Venezuela. State plans to curb illegal mining and retrain miners failed. And, in a twist, armed groups penetrated the deposits with official endorsement and the mining dynamics expanded in such a way that it could be said that in the south of the country, the way of life is totally different.

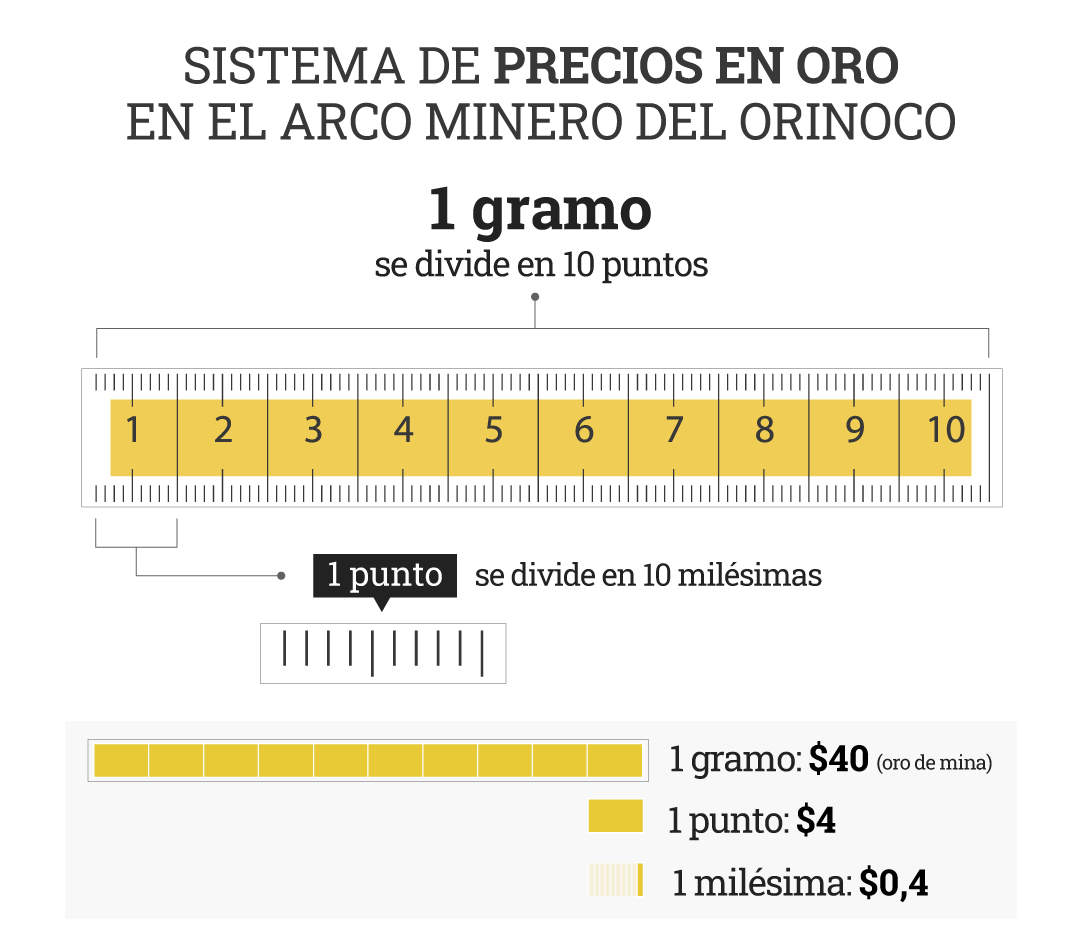

Men and women who have migrated to places like El Dorado, Las Claritas or Kilómetro 88 have had to adapt to a new economy with a price scheme in thousandths, points and grams of gold, unknown in the rest of the country. It is a kind of financial system based on the precious metal invented in the mining areas, which was strengthened and expanded during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Bills of the expired monetary cone serve as "purses" of the grams or gold points that are used as exchange currency in the mining towns of the Bolívar state

Bills of the expired monetary cone serve as "purses" of the grams or gold points that are used as exchange currency in the mining towns of the Bolívar state

It is not an extended mechanism throughout the state, but with intensity in mining municipalities such as Sifontes, where products in markets, restaurants and all kinds of formal establishments are traded under this modality. The legal minimum wage of $16 a month is a joke in daily mining.

In this way, an hour of Wi-Fi connection costs 0.02 grams of gold; a lunch, 0.06 grams; a mattress, 2 grams; and four beers, a point of gold that is equivalent to 0.1 grams of the metal.

In supermarkets, prices are expressed in gold and there are checkouts only for payment with the precious metal. They have a scale to weigh it, tools to make the cut and even torches to heat the gold and verify that it is real. In the burning process, the mercury with which the metal was amalgamated evaporates, contaminates and sickens silently.

The prices of products and basic services, from Tumeremo to Kilómetro 88, are expressed in gold. Swipe and see the complete photo gallery

The fuel, which is plentiful in Troncal 10 which goes across the mining municipalities, is sold at 0.6 thousandths of gold, the equivalent of 2.7 dollars, an amount that usually varies depending on the price of the metal. The offer also has a variant with respect to the rest of the country: the fuel, with an intense red color that resembles a sweet soda flavored with tutti-frutti, is packaged by hand in soft-drink bottles of different sizes. It is trafficked illegally from Guyana and is mainly obtained in the municipality of Sifontes. It is no coincidence, because this is the border with the Essequibo territory.

In addition to this "golden" economy with non-typical supply, it is common to make transactions in bolivares in cash, an operation that even in the cities of Bolívar is unusual due to the shortage of paper money. The distortions created by mining dynamics complicate the lives of wage earners such as teachers or civil servants, who receive their deteriorated salaries through deposits in bank accounts. In Roscio, El Callao and Sifontes, the three municipalities south of Bolívar that are part of the Arco Minero del Orinoco, the use of points of sale or transfers is not usual because the banking infrastructure is weak or non-existent and the telecommunications signal is poor or absent in areas such as Km 88, Las Claritas and El Dorado.

Economic performance is closely linked to gold production. In Tumeremo, Sifontes municipality, sales in the business sector have decreased in the last year. Hotel occupancy, which is a thermometer for the commercial union, has also dropped. Erick Leiva, business leader and former president of the Sifontes Chamber of Commerce, attributes the drop in commercial movement to a decline in gold production. He presumes that this trend is due to insecurity in the mines due to the presence of armed groups and the constant collection of bribes from miners. "Everything that generates profit is controlled by the “colectivos” inside the mine."

The situation has generated a level of misery that they did not see for years. "We have seen young people, children, teenagers, elderly people begging in the streets, begging for food, asking to be given something, digging through the garbage. They are not from Tumeremo and it is worrying the apathy in which we are falling, the social decadence. We have mining activity and it is the one that had made this not happen. As (mining activity) decreases, we see these situations," he said.

In El Callao, the foundation of joint ventures and strategic alliances to exploit the Arco Minero del Orinoco has generated the displacement of miners from traditional exploitation areas. State practice has trampled on the supposed inclusion, dignification and regularization that the state megaproject aspired to with mechanisms such as the Single Mining Registry and the Mining Brigades.

"This opening has not benefited the municipality's sustainable development because small-scale mining feels displaced. This has been handed over to large companies and the traditional miner feels downgraded, run over and that has brought social consequences in El Callao," Mayor Coromoto Lugo said. Some mines such as La Increíble, previously opened to small miners, are being handed over to strategic alliances, he denounced.

The mayor of El Callao maintains that the "great mining opening" has not left social benefits for the municipality. "Here, there is a great social injustice," he said.

The mayor of El Callao maintains that the "great mining opening" has not left social benefits for the municipality. "Here, there is a great social injustice," he said.

The president of the Chamber of Commerce of El Callao, Ceferino Chacín, maintains that large companies "no longer move anything" because they do not contribute to social development or acquire inputs or services in the locality. "They must give mining concessions to the miners, who are the ones who mobilize the economy. The ordinary miners, the artisanal, native, the traditional one who has always worked in mining. Those are the ones that really move the southern municipalities, those who have to buy food in those municipalities, so that the municipalities get ahead and the mayors can collect their taxes."

"These plants are not investing in the municipality the wealth they extract within the municipality itself. Just as they take gold out of the region, they should be investing here. It looks bad that you are taking the gold and you are not leaving anything for the people. In El Callao we do not want to end up like El Pao," he said, referring to the town in the Piar municipality of Bolívar state that was forgotten after intense iron ore exploitation for 40 years.

In El Callao, the miners have been displaced from the mines where they traditionally extracted gold in an artisanal way. Swipe and see the complete photo gallery

With the lack of answers to problems fear returns. During the pandemic, 700 phone lines of the state-owned Cantv were down. The electricity went out up to three times a day and, as in other towns, they have four years without water service by pipes, an element that gold processing plants and mills require in abundance. "In the pandemic we worked four hours a day, many businesses went bankrupt. 40% closed in the pandemic and have not reopened," he underlined.

"We do not stop asking ourselves why the deterioration if there is so much gold exploitation. Why has there been no investment in services, telephone, water, electricity? There is no improvement in services but there is greater consumption of electricity, for example. If you don't invest in this, what can we expect?" he added.

In the mining town of El Dorado, for example, it is the "Negro Fabio" syndicate —nickname of Fabio Enrique González Isaza, leader of one of the criminal gangs operating in the municipality of Sifontes— that has been responsible for containing social unrest. He not only controls the gold deposits, but also recovers common areas of the town, donates medical and sports supplies, builds or refurbishes schools and outpatient clinics and solves the main problems of public services. He has become a kind of reference for the youngest. He does make sure that children do not see him armed. Meets with local authorities and government representatives; and "delivers justice" to those who steal or rape. But there are problems he cannot stop: the increase in drug use and prostitution. "There are girls who have deserted and go to the mines to prostitute themselves, girls aged 13, 14 and 15," said a teacher.

Eumelys Moya, coordinator of the Human Rights Center of the UCAB Guayana, argues that the violence in the mining areas of Bolívar is structural and that prostitution is also exercised for survival and as a way to get food, which is considered a form of modern slavery.

"That structural violence is a constant"

Even cultural gaps are at risk. In El Callao, most of the 200 goldsmith workshops in the town have closed. Those who remain are counted on the fingers of one hand. They have migrated to mining or work with silver, contradictorily, in the gold heart of the country.

Business associations have tried to promote other productive sectors: multipurpose farms; livestock feed production; tourism routes; setting up of dairy pasteurization plants; non-traditional coffee, cocoa, and potatoes farming in elevated areas. But in a context not only of uncontrolled mining but also of violence, with the increase in kidnappings and threats, there is a consensus: "As long as there is insecurity we are not going to generate anything."