Indigenous leaders affirm that communities want to take justice into their own hands. The invasion of land, in the surroundings and interior of their territories in southern Bolívar, intensified during the pandemic. Armed groups perform control and smuggle in weapons and drugs. They threaten directly. No security force stops the attack. They feel alone in a daily war.

The occupation of indigenous lands has been evident in the San Antonio de Roscio indigenous community. The most recent sign is the irruption of dozens of informal sales of mining supplies on a long stretch of highway that is now known as "Los Kilómetros"

The occupation of indigenous lands has been evident in the San Antonio de Roscio indigenous community. The most recent sign is the irruption of dozens of informal sales of mining supplies on a long stretch of highway that is now known as "Los Kilómetros"

The indigenous captain felt no fear. Cecilio Bigott, a 50-year-old brown-skinned Pemón who was just elected community authority in July 2021, was targeted by 25 armed men in broad daylight at Kilómetro 27 of Troncal 10, on the lands of the San Antonio de Roscio indigenous community, in the Sifontes municipality south of Bolívar. within the boundaries of the Arco Minero del Orinoco.

"One has to die," says Alejandro Lezama, another indigenous leader in the community. It is the warrior spirit of the indigenous, he adds, but the indigenous had no way to defend themselves. William was aiming at the captain at close range and only his pulse trembled when Bigott urged him to shoot. His wife accompanied him. The gunman lowered the weapon. He threatened to abuse the vice-captain, but the attempt to pull the trigger dissipated. At least for that moment.

Members of the captaincy were trying to mediate in a community conflict in the new frantic commercial section of the village, where the action of armed groups thirsty for gold has arrived. “That's why I faced them, I wasn't afraid. I walked with my security, my family, the board of directors, with God,” he insists.

Bigott —with a serious look and slow speech— shows on his cell phone, without coverage in these deep entrails of Bolívar, a map with straight lines that meet and delimit the lands of San Antonio de Roscio. Despite the debt in the demarcation, established in the 1999 Constitution, the indigenous communities know precisely the limits of their territories. These traces are a certainty of the lands that ancestrally belong to them.

Until a few years ago their territories seemed infinite. The green layer extended beyond what his eyes could see. But that invisible border line is moving increasingly toward the center as criminal groups advance. It's as if the owner of a huge 20-room property was stripped day after day, month after month, year after year, a room and then another and then another and then another... until he is confined in a small space without control of what once belonged to him.

And what once belonged to him, but is now dominated by armed groups, was an elementary part of his life and memory: the space to hunt, to fish, to plant, traditional activities that are weakened voluntarily and involuntarily. "How did they get there? We don't know. Suddenly they came as mere miners. Now they are a powerful organization, which we have already realized that sometimes the government – it hurts to say it – has ties with them and that is why it is so difficult to eradicate them. They are harsh realities that we sometimes tell them and I know that the government is offended," observes the Pemón captain.

In the community there is no telephone signal to warn of threats at the moment. There is also no police station and communities fear that, even if there were, the pressure from armed groups would not cease. Bigott recalls that when he suffered the aggression, uniformed members of the Bolivarian National Guard traveled along the road and did nothing.

San Antonio de Roscio is a Pemon indigenous community located between Kilómetro 24 and 41 of Troncal 10, which connects Venezuela with northern Brazil. The ancestors founded it 60 years ago. Its captain remembers that it was always a quiet community. He, a native of Kamarata in the municipality of Gran Sabana, arrived with his parents when he was just two years old. There he learned to fish, hunt and plant. But that image of childhood has mutated profoundly in the last decade and, more severely, in the last two years, so much so that it is not the same reality that his three grandchildren now live.

The incursion of armed groups began in mining areas on the periphery a decade ago and are currently a few kilometers from the community, where about two thousand people live, according to local censuses.

With the map in hand, Bigott specifies that they are cornered. He has been convinced by the journeys, facts and evidence accumulated during his eight years as indigenous security, a role he played before being elected captain.

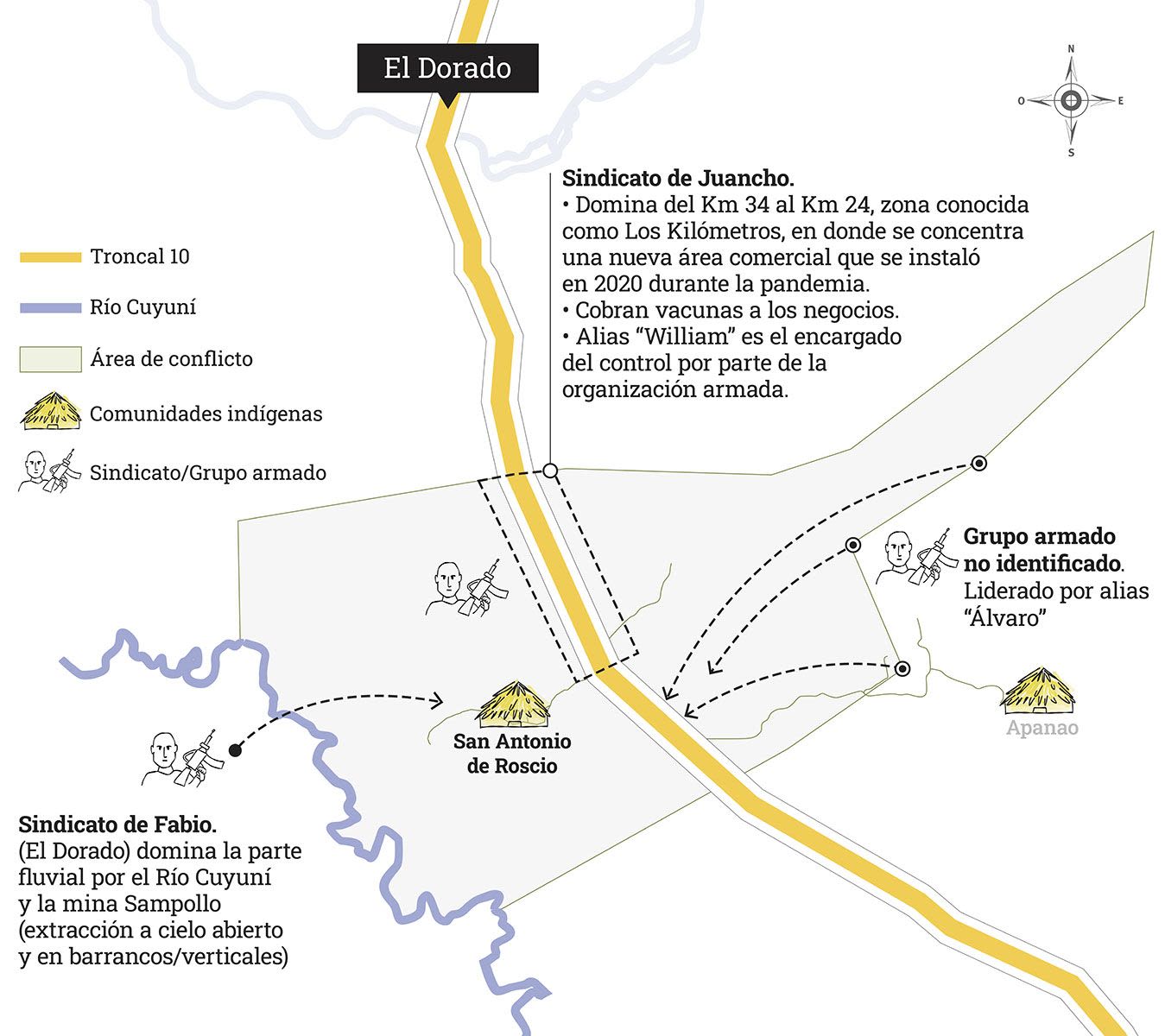

The "syndicate" of "Negro Fabio," the "pran" that has controlled the gold deposits in El Dorado for more than a decade, dominates to the west the fluvial zone by the Cuyuní River and a portion of the San Antonio jurisdiction, where the Sanpollo mine is located. The captain acknowledges that they allowed them to operate in the deposit because it was distant from the community, "but now they are getting closer because as they exploit the land, they are running out of land and they are getting closer and they are cornering us."

To the south, they are surrounded by the "Juancho" syndicate that dominates Las Claritas and Kilómetro 88 and, to the east, they identify a criminal named Álvaro, who they presume responds to Juancho's armed group.

The armed groups are not satisfied with the mines that already control the outer limits of indigenous territory. They now want to penetrate the deposits guarded and operated by the community itself, which defends the right to exploit the land as a measure of self-management. "What are they worried about now? Grab the mines that the community has, that are guarded by us and that we administer for the self-management of the community, to make government, to give an incentive to teachers, to doctors," mentions Lezama.

Although they have not reached the mines exploited by the indigenous community, the invasion of lands has become evident in the heart of San Antonio de Roscio, on both sides of Kilómetro 24 to 34. There, non-indigenous people set up shops and stalls. They took the area during 2020 and 2021, in the middle of the pandemic. In the sector, full of businesses of all kinds and now known as "Los Kilómetros", armed groups collect bribes. From the coffee seller to the merchant of gasoline per liter, even smuggled from Guyana, it is under the domination of armed groups, they affirm. The control is held by William, the same who pointed to Bigott along with 25 other men, who answer to the "Juancho" syndicate.

PHOTO GALLERY. The collection of bribes in "Los Kilómetros" is controlled by Juancho's "sindicato" (union), which operates in Las Claritas. Swipe and see the complete photo gallery

Near the "shopping center", as they call it, are the Sanpollo, La Lira, León and San Jaime mines. There are no gold processing plants, but open-pit mines and mills.

The captain of San Antonio de Roscio recalls that a couple of decades ago there was a mining presence, but not violence. They have gone so far as to doubt their own actions. In a mea culpa, they reflect on whether they have been permissive towards foreigners who have entered their territory. The consequences are so far out of sight. Armed groups collect bribe payments, exploit the miner and repress; street traders have brought drugs into the community; food prices have risen because of the bribes charged by criminals; and it would not be a surprise if children and young people encounter armed men.

In their eagerness to expand and extend control, criminals have wanted to negotiate. In San Antonio they have not met; they refuse to do so. "When there have been situations of abuse, it has always been confronted, 'stay on your limit, respect us', it has not been about sitting down to negotiate, but to maintain tranquility, but never to talk about agreements or businesses because they are irregular groups. We can talk to ministers, mayors and governors, because they are established institutions, but what do I do talking to irregular groups? indigenous communities are not here to make those kinds of alliances,” Lezama said.

In the official maps of the Arco Minero del Orinoco, there is no identification of indigenous communities, hamlets or villages. The large blocks in degraded green only show minerals to be exploited: gold, quartz and granite, in the case of Bloque 4 Josefa Camejo where the southern section is located, integrated by the municipalities of Roscio, El Callao and Sifontes.

The establishment of the Arco Minero del Orinoco, a megaproject that harms the cultural, social and economic integrity of indigenous people, did not provide information and prior consultation with indigenous communities on the use of natural resources in their habitats by the State, as is based on Article 120 of the Venezuelan Constitution.

Conflicts over control of deposits have been fueled in the last two years and the communities that for years have inhabited southern Bolívar, absent from official cartography, have been the most affected. It is much more that has not leaked to the press, but highlights in February 2021 the invasion of lands of the San Luis de Morichal community by irregular groups on the Chicanán River.

An event that occurred at the beginning of 2022 confirms the threats to indigenous peoples and the escalation of violence. The conflict occurred in a neighboring community of San Antonio de Roscio.

For five years there were disputes over the occupation of a warehouse –at Kilómetro 82 of Troncal 10 on land belonging to the Santa Lucía de Inaway indigenous community– abandoned more than 30 years ago. Inhabitants of Sororopan, Inaway, San Miguel, Araima Tepui and Joboshirima, near the property, decided to occupy it to install a community sale.

The shed, in whose surroundings the armed groups attacked the indigenous communities, is located just two kilometers from a military checkpoint

The shed, in whose surroundings the armed groups attacked the indigenous communities, is located just two kilometers from a military checkpoint

The dirty road in front of the large brick warehouse, a few meters from the main road, leads to a wall, a gate and a kind of informal checkpoint. The illegal checkpoint is a “mecate”, as the armed groups call the surveillance post. There, the "Juancho" syndicate monitors who enters and leaves the mining deposit in the area, collects bribes for the transfer of gold and supplies, imposes punishments and resolves problems in their own way.

"Before, the indigenous passed through there because they were their trails to go to the Cuyuní River to fish, but now they can't do that because they don't let them pass. There are lagoons back there and they are working on them, there are also companies back there in the Mesones sector. ‘El viejo Darwin' is in control," said one indigenous.

To prevent indigenous communities from occupying the warehouse, the armed group had the communal councils occupy it first and also act as their spokespersons. They are an appendix, affirm the indigenous. "They use the people as a shield."

Joboshirima's captain, Junior Francis, arrived at 11:42 a.m. on January 12, 2022, at the land where the warehouse is located. Indigenous people from the nearby Inaway indigenous community asked for support because someone was taking over the infrastructure. Francis did not know exactly what was happening, but he moved with six young people from his community to the point of conflict, where members of the indigenous community security had already arrived.

Joboshirima is a community mainly of the Arawak people but with the presence of Pemón and Kariña indigenous people. Its captain was attacked by Juancho's "union" in January 2022

Joboshirima is a community mainly of the Arawak people but with the presence of Pemón and Kariña indigenous people. Its captain was attacked by Juancho's "union" in January 2022

Joboshirima is a community mainly of the Arawak people but with the presence of Pemón and Caribe indigenous people. The name in huge letters is on the central esplanade of the village on Troncal 10, just over 10 kilometers from the Las Claritas mining town.

On the ground were two members of the "Juancho" syndicate, nicknamed "el Causa" and "Yorman." They carried long weapons. For the indigenous community, there were mainly women and members of indigenous security. The men boarded three SUV trucks that left from the access road near the warehouse. They fired into the air. The criminal high command was in full: "Juancho", "Humbertico", and "el viejo Darwin", or "Johan Petrica", founder of the Tren de Aragua, one of the most powerful criminal groups in Venezuela.

The impacts paralyzed him. "They're killing the brothers," Francis thought. At that moment, he reacted, grabbed the phone and started taking pictures. "Yorman" ran to take away his equipment. "I put the phone in my boxer shorts and the guy —as I got up— hit me and broke my nose." Two members of the indigenous security of Saint Lucia de Inaway were also assaulted.

The indigenous looked for the National Guard. The shooting had passed, but they wanted to knock down the checkpoint of the criminal groups. They couldn't. The men were armed and had locked the gate. Without reservation, they pointed rifles at the military. "We're going to pump us full of lead," they told them.

“They have already broken the barrier, if that had happened to one of their leaders… I told Juancho, if this had happened to one of the leaders, ‘what would you have done?’ It would not have ended like this, it would have been a massacre. And we, with everything and that, have called for dialogue to leave things in peace,” said an indigenous person who witnessed the conflict.

For indigenous leaders, armed groups are present on the official mining map. "The government doesn't support us. They (armed groups) say they have the support and in front of everyone's eyes, the government is the one that is raising them because where do they get weapons from, what does the Guard do? What do the police do? What does the Sebin do when they are there? They must be 'eating' (benefiting) there. For a group of people to stay in power, they must be feeding those at the top, because how do you stay there?" said an indigenous leader.

In front of the Kilómetro 82 shed, there is an earth movement and heavy machinery. Indigenous people point out that it is a mill that will have a cyanidation plant in 2023

In front of the Kilómetro 82 shed, there is an earth movement and heavy machinery. Indigenous people point out that it is a mill that will have a cyanidation plant in 2023

The armed group forced the closure of shops in Las Claritas, sources coincided. The miners who were in open-pit deposits were put in vehicles and taken in pickup trucks to the land of the warehouse. Dozens of people also arrived around the warehouse, forced by the communal councils. They kept them there relentlessly.

The roadblock stopped for six days, on both sides of the road, private vehicles and passenger transport that travel to and from the border with Brazil. In social networks, the requests for help from the elderly, women and children multiplied. The inhabitants of Las Claritas reported that they were running out of food due to the interruption of the way.

The six days of closure of Troncal 10 ceased on the afternoon of January 17, 2022, after a meeting in which the governor of Bolívar, Ángel Marcano, participated. At the sitting it was decided that the warehouse in dispute would remain under the authority of the Government of Bolívar and the custody of the Bolivarian National Armed Forces. It was also announced the installation of working groups to seek a solution to the conflict and analyze the problems in the sector.

It's three o'clock in the afternoon on Wednesday, January 26, 2022. The leafiness of the trees mitigates the heat outside the Pemón Samarayi Integral School, deep in the San Miguel de Betania indigenous community at Kilómetro 67 of Troncal 10 in southern Bolívar. In the courtyard they have arranged a row of tables to serve food. The deep silence breaks at times with the snoring of the motorcycles that come and go.

PHOTO GALLERY. In January 2022, 19 captains from 22 indigenous communities of the Sifontes municipality demanded again from the Bolívar Governorate and the Public Ministry an eviction plan for the armed groups from their lands. Although they would meet every 15 days, that was the only meeting in the first semester of the year. Swipe and see the complete photo gallery.

In one of the main classrooms, 19 captains of the 22 indigenous communities of the Sifontes municipality, representatives of the Pemón, Arawako, Kariña and Akawayo people that make up three axes: border (Esequibo), road (Troncal 10) and fluvial (Yuruán, Cuyuní and Chicanán rivers), meet with officials of the Government of Bolívar. The most important point of discussion is violence and land invasion. The goal is to design a plan to evict armed groups from indigenous territories.

For the government, the Secretary of Citizen Security, Edgar Colina Reyes; and representatives of the Public Ministry and the Integral Defense Operational Zone (Zona Operativa de Defensa Integral - ZODI) are there. Hours and hours lead nowhere. There are no conclusions, except the promise to meet again in 15 days and once a month to review progress.

But it is not the first time that they expose the situation. The presence of armed groups in indigenous territories began in 2007. Since then, at least seven state and security bodies have received complaints from the indigenous communities of southern Bolívar: the Foreign Ministry, the Strategic Operational Command of the Bolivarian National Armed Forces (Ceofanb), the Ombudsman's Office, the Prosecutor's Office, Government of Bolívar,, the Strategic Region for Integral Defense (REDI) and ZODI. None has acted so far, warns the captain general of the Cuyuní IV sector, Luis Miranda.

What do you want? that we arm ourselves too? What is your role? What are you doing? What answer are you giving us?

Silence and inertia have given way to violence. Between 2016 and 2019, according to the calculations of the captaincy, armed groups have killed six indigenous people in San Antonio de Roscio and two in San Luis de Morichal, but also Santa Lucía de Inaway, Joboshirima and San Martín de Turumbán are affected by the presence of armed groups.

"Part of the mines are taken, but there are mines closer to the communities of which they want to take control and the community is facing this through its communal and sectoral security and asking the State to do something before it becomes major, that is the point of demand, claiming a constitutional right.

"Three murders of indigenous people still shake San Antonio de Roscio. The community keeps records. The first was that of Domingo Pérez, a 25-year-old Pemón owner of hydraulic motors. They wanted to invade his land; he refused and was ambushed. "In the presence of his wife they captured him, took him to a place and after two hours she found him dead, naked and tortured. We saw the body, after killing him they took him to a neighboring community. It was the first tragedy," say San Antonio residents.

The second was the disappearance and murder of Oscar Meya. Although he was from San Luis de Morichal, he had relatives in San Antonio. An armed group captured him, tortured him and disappeared. His body has not yet appeared. His relatives doubt it will. The third case is that of Anthony Martínez. He was traveling in a boat on the Chicanán River with members of the indigenous security. They were ambushed and shot. “Until the sun of today we did not know what happened to Anthony. How we would like to sit down sometime to ask what they did to him”.

Indigenous communities defend the right to exploit the mines in their territories as self-management and to prevent the expansion and control of armed groups

Indigenous communities defend the right to exploit the mines in their territories as self-management and to prevent the expansion and control of armed groups

Water pollution, malaria proliferation and even migration have been other consequences generated by the expansion of mining and land invasion. Indigenous leaders agree that communities want to take justice into their own hands "and we as leaders are trying to bring peace so that that does not happen, because we know the consequences that can bring. We are still giving a vote of confidence to the state to do its job, but our people do not lack the desire to confront when they see that the State does not do its job.”

"If something happens and there is a confrontation between these armed groups and indigenous communities occurs and it is a massacre, who are they going to see in front of international eyes as the bad guy, because we have done everything possible to inform the competent institutions so that they take actions but they are not doing it," they reiterate.

The complaints have been with name and surname, because the outsiders –already converted into parallel governments– have more than a decade of action. No one reviews the claims nor are there detainees among those singled out by indigenous communities for invading their territories, assaulting and murdering.

"The threat continues, but I'm not going to do business with them. They're looking for me, but I'm not going to give myself up so easily. I'm going to keep fighting."