Canaima

A paradise poisoned by gold

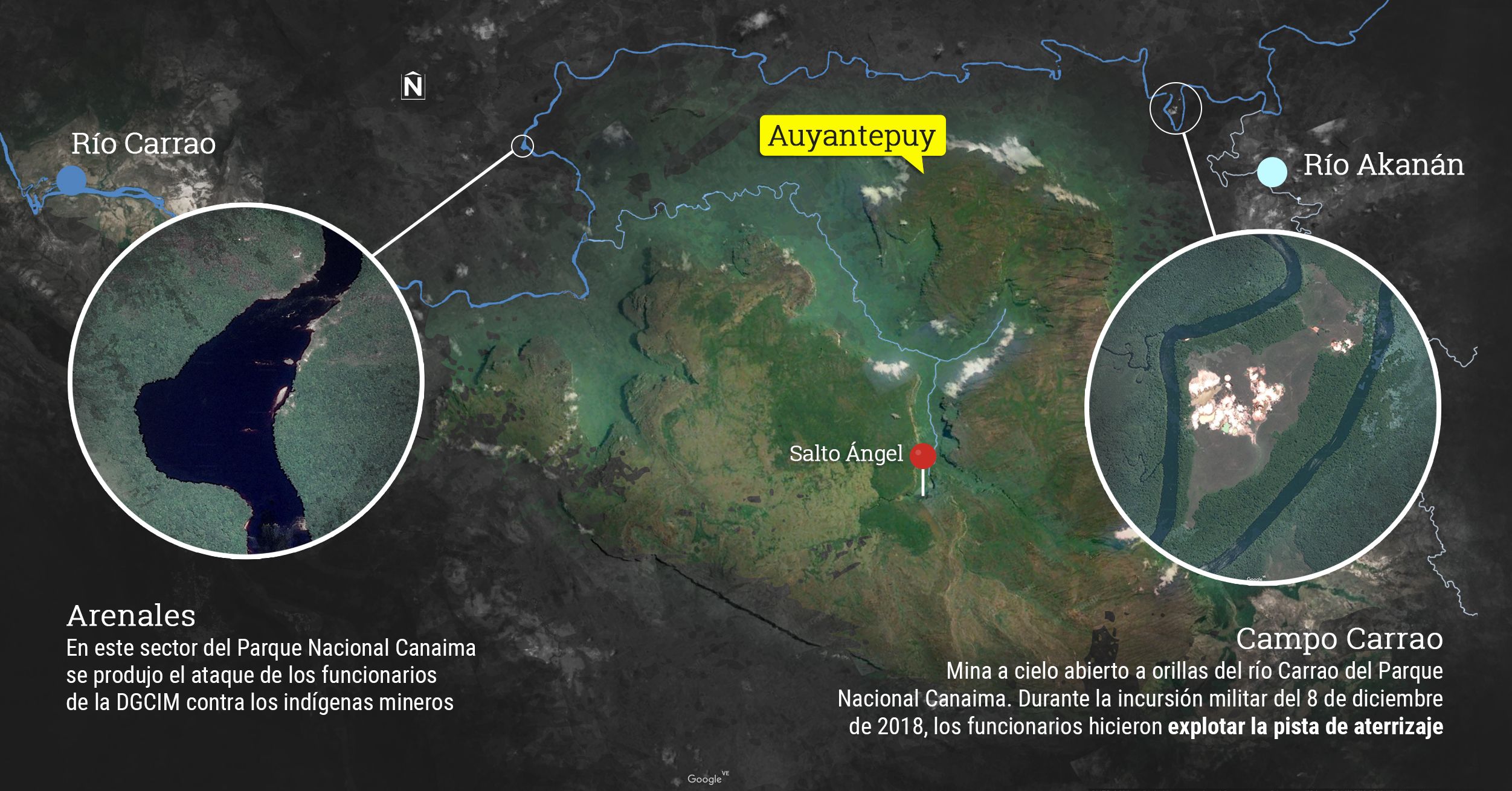

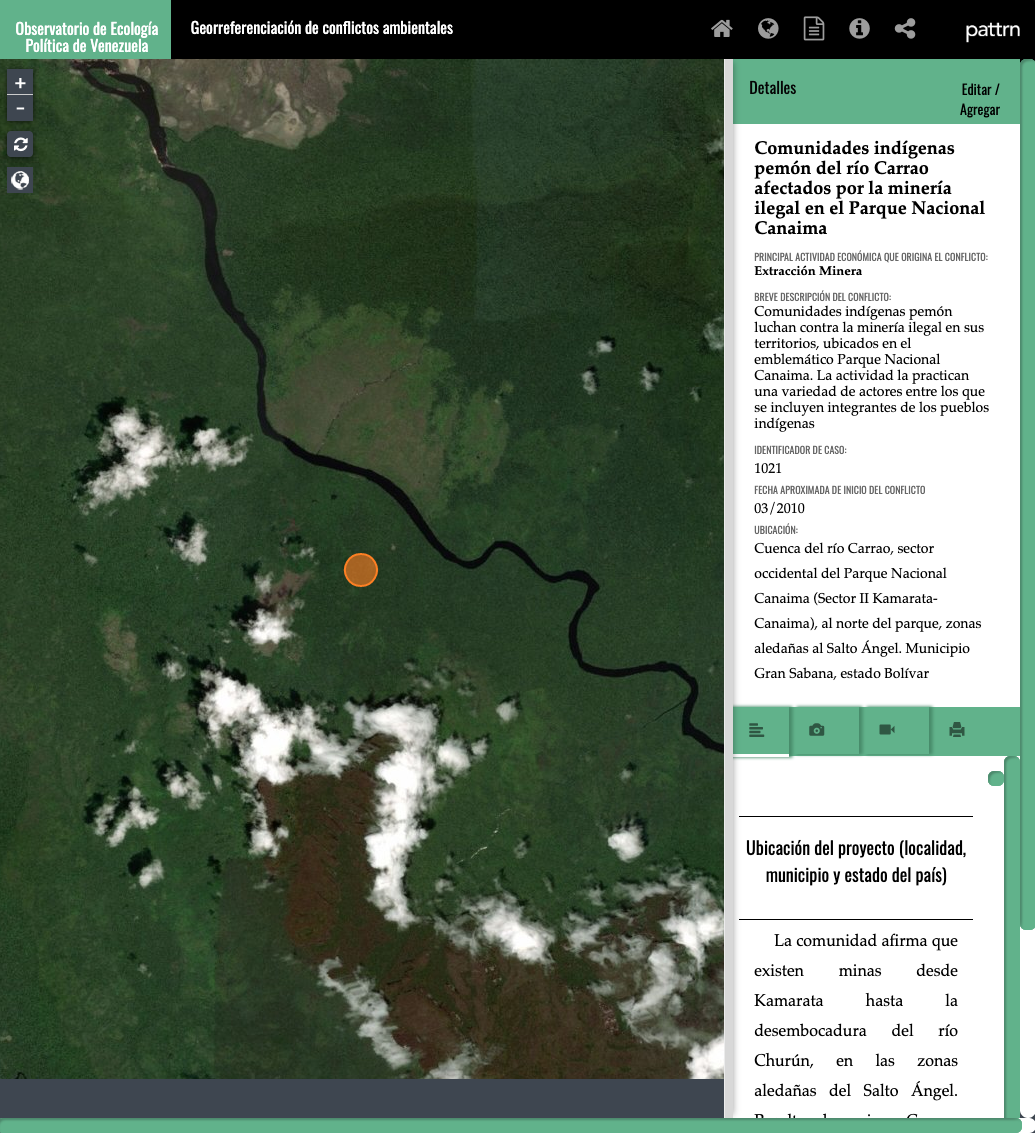

Just 14 miles from the renowned Angel Falls, the highest waterfall on the planet that inspired the movie Up, there is at least a score of makeshift barges and an open-pit mine where hundreds of men and women go to work every day.

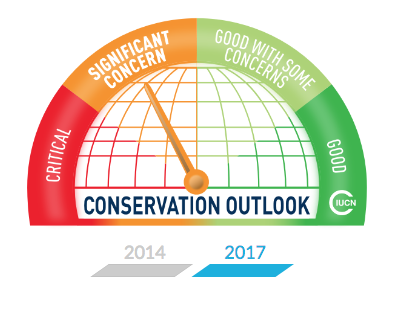

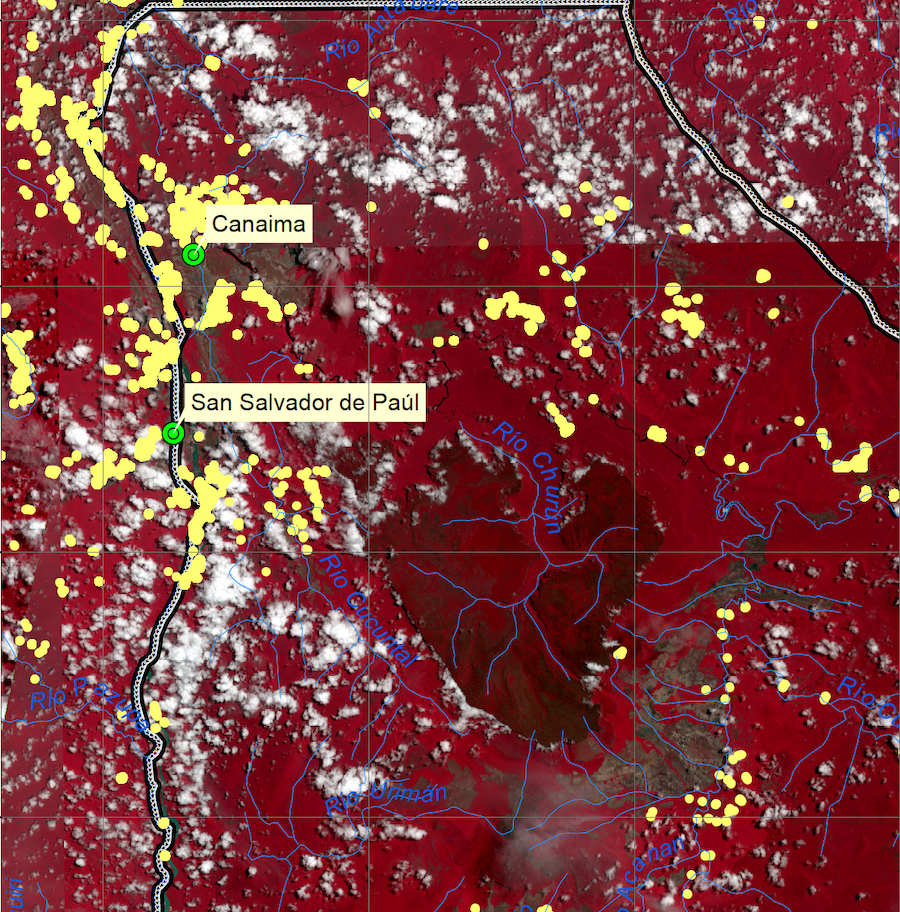

After a flyover of the western section of Canaima and more than 30 hours of navigation on the Carrao River, Runrun.es got a firsthand account of how these miners work inside Canaima National Park. Declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO, the park was placed under an “orange alert” in 2018, after significant concern was raised over mining activities in the area as well as its devastating impact on the environment and local residents.

Mining sites in Canaima are controlled by the original inhabitants: the Pemón ethnic group. Driven by the collapse of tourism in the area, they have turned to illegal mining in order to survive.

Gold extracted from this ancient landscape is taken on board light aircrafts owned by a local businessman who has been accused by the Venezuelan Public Prosecutor’s Office of being a member of a trafficking network that transports the metal from Venezuela to the Caribbean islands.

This same person is linked to a luxury lodge located inside Canaima National Park. According to the Pemón indigenous people, an armed attack ordered by the President of Venezuela, Nicolás Maduro, “to put an end to mining” was planned here on December 8, 2018. Once perpetrated, it forever altered Canaima and its inhabitants.

Gold mining in Canaima is recognized by indigenous organizations which, according to sources, originated in the last five years to regulate the mining activity.

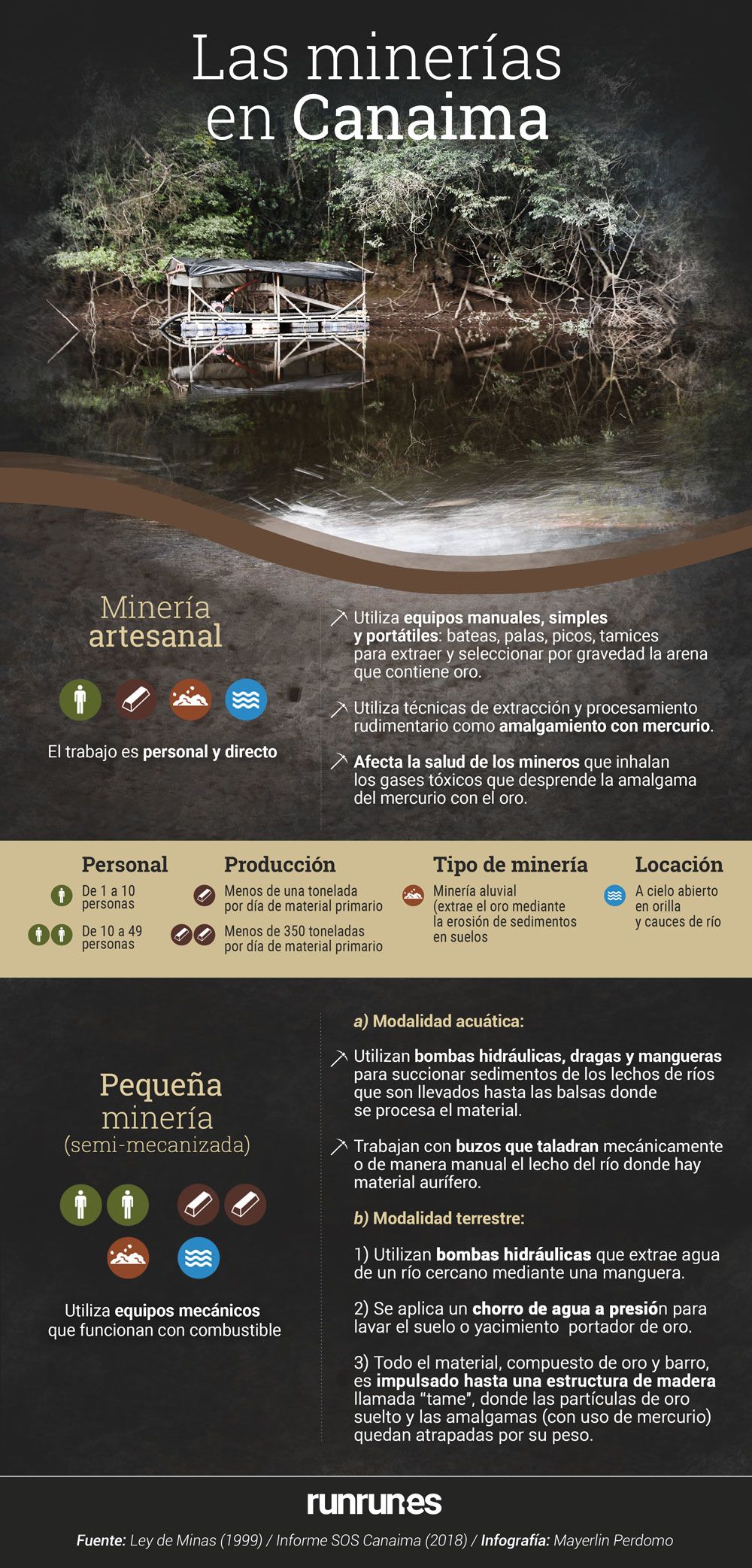

The danger of small-scale and artisanal mining in Canaima is that the mercury employed is highly contaminant and affects not only the rivers’ water, but also the fauna and local population. It also causes rainforest deforestation and sedimentation of the Carrao River, a tributary of the already contaminated Caroní River which flows into the Guri Reservoir. 85% of Venezuela’s electricity is generated here. With an ongoing energy crisis throughout the country, more damage to this natural area would be catastrophic.

Esta investigación la encuentra en español gracias al apoyo de nuestros lectores y clientes, y se puede visitar haciendo clic en este enlace https://alianza.shorthandstories.com/canaima-el-paraiso-envenenado-por-el-oro/index.html

A night among the mines

Indigenous peoples extract gold in the dark

An unexpected blow pulls the curiara from its course. It is nighttime and the dugout is navigating through the Carrao River, in the banks of the Auyantepui, one of the largest tabletops in the Guiana Highlands. A map will show that the boat is right in the heart of Canaima National Park, located in Southern Venezuela. Darkness keeps the travelers guessing as to what exactly crashed into and almost capsized the narrow vessel. Only the motorista (steerer) and the proero (bowman), veteran indigenous people belonging to the Pemón ethnic group, can tell that the obstacle in question is an artificial sand mound. Ever since gold searchers began swarming the area, there are plenty of them lying below the river’s dark waters.

From a distance, lights signal the proximity of an open-pit mine, the likes of which abound downstream the Arenal sector of the Carrao River. The purring sound of the dugout’s engine makes the lights go out completely. The boat reaches a camp traditionally reserved for tourists. It is dark and occupied by the women in charge of preparing meals and washing clothes for the nearby miners. They hurriedly leave as the travelers disembark. After dinner, the travelers quickly wrap themselves in their hammocks. Mosquito nets protect them against malaria, a disease endemic to gold mining. They go to sleep amidst the sounds of frogs croaking, yet there is another unmistakable sound lulling about: it is the distant rattle of machines processing gold extracted from the sandy depths of the Carrao River. Such is the scene in front of the majestic Wei-Tepui or the tepui of the Sun.

A tourist camp is provisionally occupied by the indigenous people who work in the mines of Carrao River. Photo: Lisseth Boon.

A tourist camp is provisionally occupied by the indigenous people who work in the mines of Carrao River. Photo: Lisseth Boon.

In the Western sector of Canaima National Park, there is an agreement between the Pemón, traditional inhabitants of these ancient lands, to work in the mines only at night. They do so to avoid being seen by the ever less frequent tourists who visit this natural reserve. Declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1994, nowadays there is no way to hide the destruction. In broad daylight, one can see gasoline drums dumped on the shores of the rivers while the so-called “balsas mineras”, a poor man’s version of a barge, float nearby. These makeshift barges are not meant for navigation. Their sole purpose is to float and hold the machines that dredge river beds in search for gold.

On a 36-hour journey down the rivers of Canaima National Park, Runrun.es was able to count 21 active barges: one in the mouth of the Akanan River, five throughout the waters of Carrao River and 14 in the Arenal sector. All of them float around the millenary landscape with no specific order or direction. Yet, they are not the only evidence of mining in the area. Navigators must avoid their curiaras from becoming tangled with the floating “puntos”, buoys crafted with rope and plastic bottles, which signal a soon to be mined gold vein.

A makeshift barge in the Carrao River. Photo: Lisseth Boon.

A makeshift barge in the Carrao River. Photo: Lisseth Boon.

“If they keep on mining gold like this, the Carrao River is going to end up like the Arekuna (camp) in the Caroní River which is all brownish because of the amount of barges surrounding it”, says R.C., a veteran tour guide in Canaima and a fierce critic of gold mining. He watches the soft wake the curiara leaves on the caramel colored waters. It is the color of the Carrao River. Years before, the Caroní River, the second most important river in Venezuela, used to have this color. Today, mining has troubled its waters.

An aerial view from the light plane which will shortly land in Canaima’s small airport shows the streaks mining has left on the borders of these theoretically sacred grounds which were declared a national park by former president Rómulo Betancourt on June 16, 1962. There is a sharp contrast on this side of tepui kingdom. On one side, are these unique, massive tabletops surrounded by jungle, savannahs and waterfalls. On the other, artificial sand quarries and radioactive green lagoons that ooze mercury gnaw at the banks of the Caroní River. Mercury is used to separate gold from sand.

An aerial view of the Caroní River in the borders of Canaima National Park. Photo: Lisseth Boon.

An aerial view of the Caroní River in the borders of Canaima National Park. Photo: Lisseth Boon.

Not even the sacred Auyantepui has freed itself from gold fever. The search for the mythical “ore bed” was the real reason behind the expedition organized by American pilot Jimmy Angel (1899-1956) with Venezuelan captain Félix Cardona Puig to fly over this heart-shaped tabletop on May 21, 1937. They returned in October, where Angel landed on the summit, damaging his plane in the process. They spent the next 11 days walking through the Auyantepui’s jungle to return to base camp, a feat which certainly fed their legend. The aviator never found gold mines in Canaima but two years later the Ministry of Public Works christened Venezuela’s iconic waterfall -“Salto del Ángel”- in his honor

A Lack of Tourism

On the banks of the Carrao River, a man with a naked torso and defiant jawbone waves through the air when he sees cameras and cellphones pointed at him from the curiaras. Nobody wants their picture taken here, much less answer questions from the few foreigners who travel through these riverbanks during the dry season.

Miners in the Carrao River. Photo: Lorena Meléndez.

Miners in the Carrao River. Photo: Lorena Meléndez.

The Pemón miners have a great lack of confidence towards strangers in this particular area. More so after the December 2018 assault which took place in the sector of Arenal. Undercover agents from the DGCIM murdered an indigenous man from Canaima and left two other wounded. This event caused a commotion throughout the Pemón tribe and transcended onto Miraflores Palace, headquarters of the Venezuelan national government in Caracas.

The fact that the Pemón, traditional inhabitants of the lands where Canaima was established, are mining gold from rivers and open-pit terrains is a reality which most would prefer to turn a blind eye. Those who have dared to speak against these practices are either ignored or attacked. Such was the case of Valentina Quintero, a journalist specialized in tourism. In November 2018 she condemned gold mining in Campo Carrao and was promptly declared “persona non grata” by the Council of General Caciques. This council, led by indigenous leaders, is a political organization created to address the rise of mining in the area.

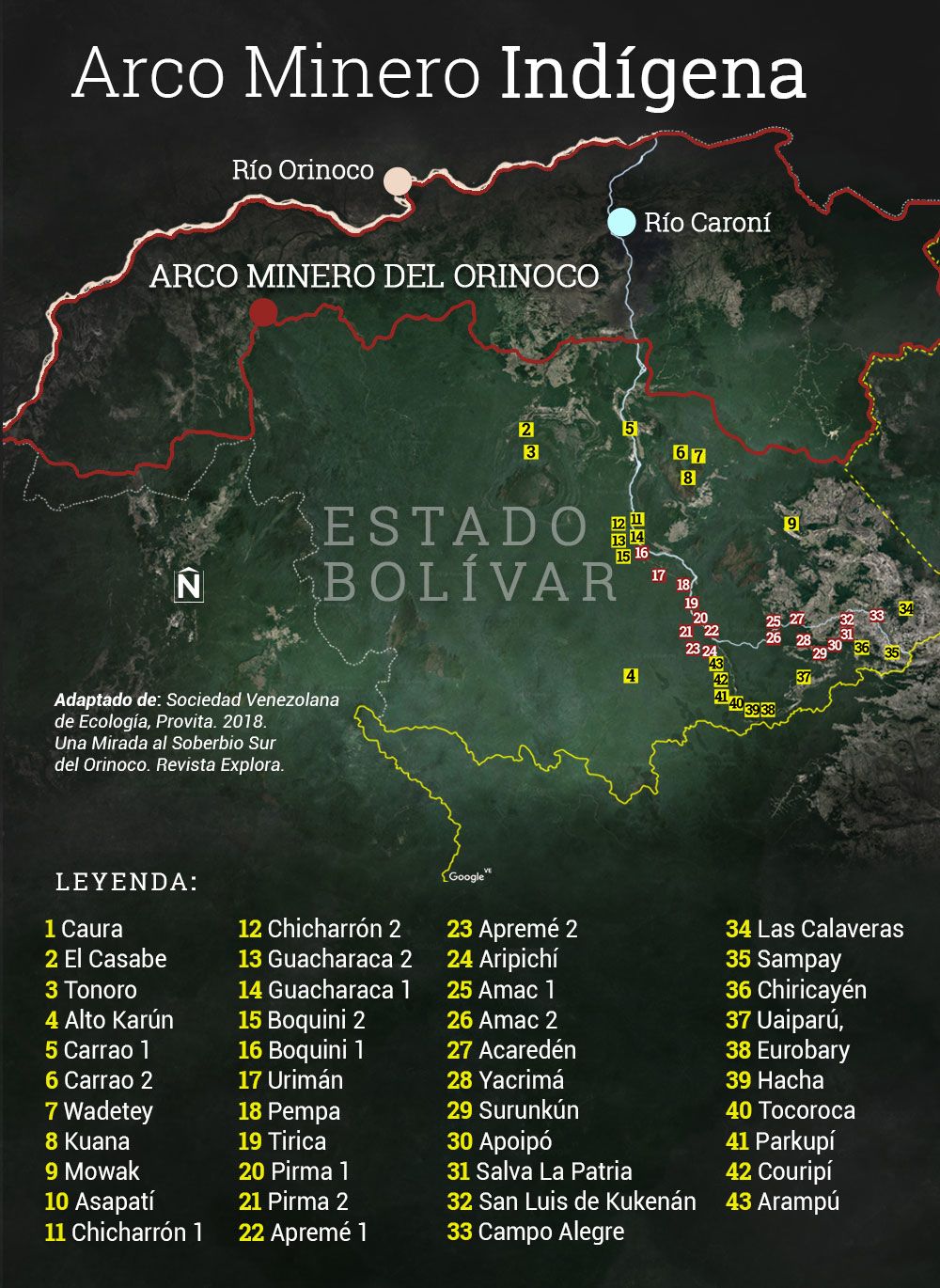

On June 4, 2019, the Minister of Environmental Mining Development and the Minister of Indigenous Peoples met with 15 caciques in the municipality of Gran Sabana, Bolívar, where Canaima is located. In that meeting the ministers reiterated that the government would protect national parks from mining operations. They also emphasized that all mining operations were to be held inside the Orinoco Mining Arc, a mining mega project which covers 43,183 square miles, roughly 12.2% of Venezuelan territory. What the government failed to mention at that meeting is that indigenous people are also involved in mining.

Runrun.es was able to prove on site that mining is not only being operated in Canaima’s borders. There is also evidence of makeshift barges dredging river beds in search for gold inside the park. An open-air pit, Campo Carrao, is just 14 miles away from the Auyantepui, the place where the largest waterfall in the planet, Angel Falls or Kerepakupai Vená (its name in Pemón language), falls at 3,212 feet high.

Gold extracted from the water and soil of this paradise is not only traded as local currency inside the park. It also appears to be smuggled outside the country as part of a contraband network. In August 2019, Tarek William Saab, the Attorney General designated by the National Constituent Assembly, issued an arrest warrant for a businessman in the tourism sector who owns several hotels in the region. Mr. Saab accused this man of using his charter planes to transport tons of gold to the Caribbean islands.

The journalists of this report went undercover through the banks of the Carrao River and the Auyantepui with the intention of documenting the events of an illegal practice in a World Heritage Site area which has been no stranger to organized crime. The protection of witness identities was imperative.

Part of the field work at Canaima National Park involved more than 20 interviews to biologists, attorneys, environmental activists, indigenous inhabitants of the region’s communities, tour operators, geologists, mining engineers and journalists. The coverage of the site was contrasted with satellite imagery.

Requests for interviews were sent out to representatives from the ministry offices of Environmental Mining Development, Indigenous People, Eco Socialism and Tourism, all of whom have authority on the matter of illegal mining in Venezuela’s national parks. As this edition went to press, there was no official response given on the evidence of mining in Canaima.

From tourism tycoon to “gold trafficker”

Charter planes smuggle the precious metal from paradise

It was the government of Nicolás Maduro who offered evidence on how gold is being trafficked from Canaima. On August 16, 2019, Tarek William Saab, the Attorney General designated by the National Constituent Assembly, issued an arrest warrant and extradition request for César Leonel Dias González, a 47 year old businessman, linked to half a dozen tourism companies in Bolívar state. Among them, the controversial Ara Merú Lodge Hotel which operates inside Canaima National Park. This hotel lodged the perpetrators of the so called “Operation Tepui Protector” (Operación Tepuy Protector), an assault carried out by the DGCIM, which left one man dead and two others wounded. All of them were Pemón.

There is no need to fly out to Canaima to become acquainted with Ara Merú Lodge. Giant billboards along the Francisco Fajardo highway in Caracas advertise it as a five star hotel “in the middle of the jungle” while radio ads saturate stations all over the country. All of this in the middle of a slumped economy where a Venezuelan worker needs to save 250 minimum wages ($6.00) to pay the average $1,500 it takes to spend a weekend for two at the national park.

This is not the first time Mr. Dias González has been linked to gold trafficking. In June 2018, his name was included in a list people involved in the so called “Operation Metal Hands” (Operación Manos de Metal) announced by former Vice President Tareck El Aissami. This operation was created to dismantle alleged gold trafficking mafia groups who smuggled the precious metal from Bolívar state. Days after this announcement, Attorney General Saab announced that the businessman was among the 39 people who were issued an arrest warrant by the Public Prosecutor’s Office.

A year and two months later, Mr. Dias González was once again identified by the Venezuelan government as a member of a trafficking network that smuggled gold from Venezuela to the Caribbean islands, mainly Dominican Republic, Aruba, Curacao and Trinidad. This time he was linked to Michael Enrique Jerez Córdoba (a private pilot) and Roberto Antonio Espejo Machado, labeled by the Attorney General as the leader of a criminal gang who is also wanted by the “Operation Metal Hands” for the crimes of theft of strategic materials and aggravated trafficking.

On August 16, 2019, the Venezuelan Public Prosecutor’s Office issued an arrest warrant requesting extradition for Dias González, Espejo Camacho and six other Venezuelans for the crimes of illicit gold trade in the Dominican Republic as well as ordering the seizure of four aircrafts and freezing of their bank assets.

Tarek William Saab: También se determinó la vinculación de César Dias González, representante legal de Transportes Aéreos del Sur y dueña de 2 aeronaves utilizadas habitualmente por Michael Jérez y Roberto Espejo para viajar a República Dominicana a comercializar el oro

— MinPublicoVE (@MinpublicoVE) August 16, 2019

Tarek William Saab: Se estableció que Cesar Dias González realizó múltiples viajes hacia Dominica, Curazao y otras islas del Caribe, destinos considerados como parte de la ruta de contrabando de nuestro recurso aurífero

— MinPublicoVE (@MinpublicoVE) August 16, 2019

Tarek William Saab: También se solicitó orden de aprehensión contra César Dias González, Roberto Espejo y los 6 venezolanos detenidos en República Dominicana; así como prohibición de enajenar y gravar bienes, además del bloqueo e inmovilización de instrumentos bancarios

— MinPublicoVE (@MinpublicoVE) August 16, 2019

To date, this extradition request has not reached Santo Domingo, as confirmed by the Office of the Solicitor General in the Dominican Republic. A Mutual Assistance Agreement in Criminal Matters signed on January 31, 1997 exists between both nations.

Workers and inhabitants of Canaima spoke to Runrun.es that Dias González has not been seen at the national park since Attorney General Saab announced the warrant requesting extradition for the gold traffickers. They can confirm that the businessman tends to his local businesses from abroad, and usually speaks with employees of Ara Merú Lodge and Camp Uruyen, located in the Kamarata Valley, to give them instructions.

In regards to his whereabouts, a new clue arose three months after the Public Prosecutor’s Office announced the warrant. On November 10, 2019, the Venezuelan Supreme Court of Justice approved Dias Gonzalez’s extradition request to the Kingdom of Spain who, unbeknownst by the Spanish Embassy in Caracas, had been detained in Madrid on September 17 by request of the Venezuelan government. The businessman had allegedly escaped the Dominican Republic where authorities detained three of his business associates (Jonathan Luciano del Valle Mata Figueroa, Esthella Gómez de Rodriguez and Claudio Alejandor Di Génova Fistarol) when they intended to travel in a private jet from the Caribbean island to Barcelona, Anzoátegui (located in northeastern Venezuela) with $1,378,000 in cash they had collected from gold sales.

The general consensus in Canaima regarding Ara Merú Lodge is that its size and facilities heavily contrast with other camps in the area which have been designed to blend in with the paradisiacal environment. Eyebrows are raised when asked who is behind this structure built in record time, with no prior studies on its environmental impact and no authorization by the National Parks Institute (INPARQUES for its acronym in Spanish) affiliated to the so-called Ministry of Eco Socialism.

The origins of its developer are also a mystery. Little is known about César Dias González’s management career before becoming the thriving tourism tycoon who opened Ara Merú Lodge in 2017. He literally landed in Southern Bolivar and began to open businesses in a protected natural area which requires a permit from INPARQUES, the governing body on national parks and monuments, as well as an alliance with at least one representative of the Pemón indigenous peoples, traditional inhabitants of the lands known as Canaima.

There is also no word on the origins of his capital. The only information available is that Mr. Dias González is registered to vote in the “Beatríz de Rodriguez” electoral center, located in Guárico state. Coincidentally, it is the same voting center of Michael Enrique Jerez Córdoba, one of his alleged associates in the gold smuggling network according to the Venezuelan Public Prosecutor’s Office.

Runrun.es tried to communicate with César Dias González to obtain his version but got no reply.

The hotel and “its wonders”

An inquiry around the Canaima Lagoon regarding the ownership of Ara Merú Lodge leads to only one name: César Dias. The businessman (whose last name has been often written in the press as “Díaz” with a z) is also credited to be the owner of several other properties: Camp Uruyen (Kamarata Valley, Canaima); Camp Waká Vená (under construction; located near Salto Hacha waterfall, Canaima); Gran Sabana Hotel (Santa Elena de Uairén, bordering Brazil) and the Posada Mediterráneo beach lodge (Los Roques archipelago). As in Caracas, enormous billboards dominate the external façade of the Carlos Manuel Piar international airport in Bolívar and ads are insistently aired in radio stations across the state.

2) G L A M P I N G | en menos de dos años este señor se apropió y construyó estos hoteles y campamentos en Parques Nacionales: En Canaima Ara Meru, Hotel Gran Sabana y Uruyen Camp. En Los Roques, La Posada Mediterráneo. Quién lava dinero a través de este testaferro? pic.twitter.com/lSIo9M9sqX

— Ricardo Delgado PEMON (@ThinKarawak) August 16, 2019

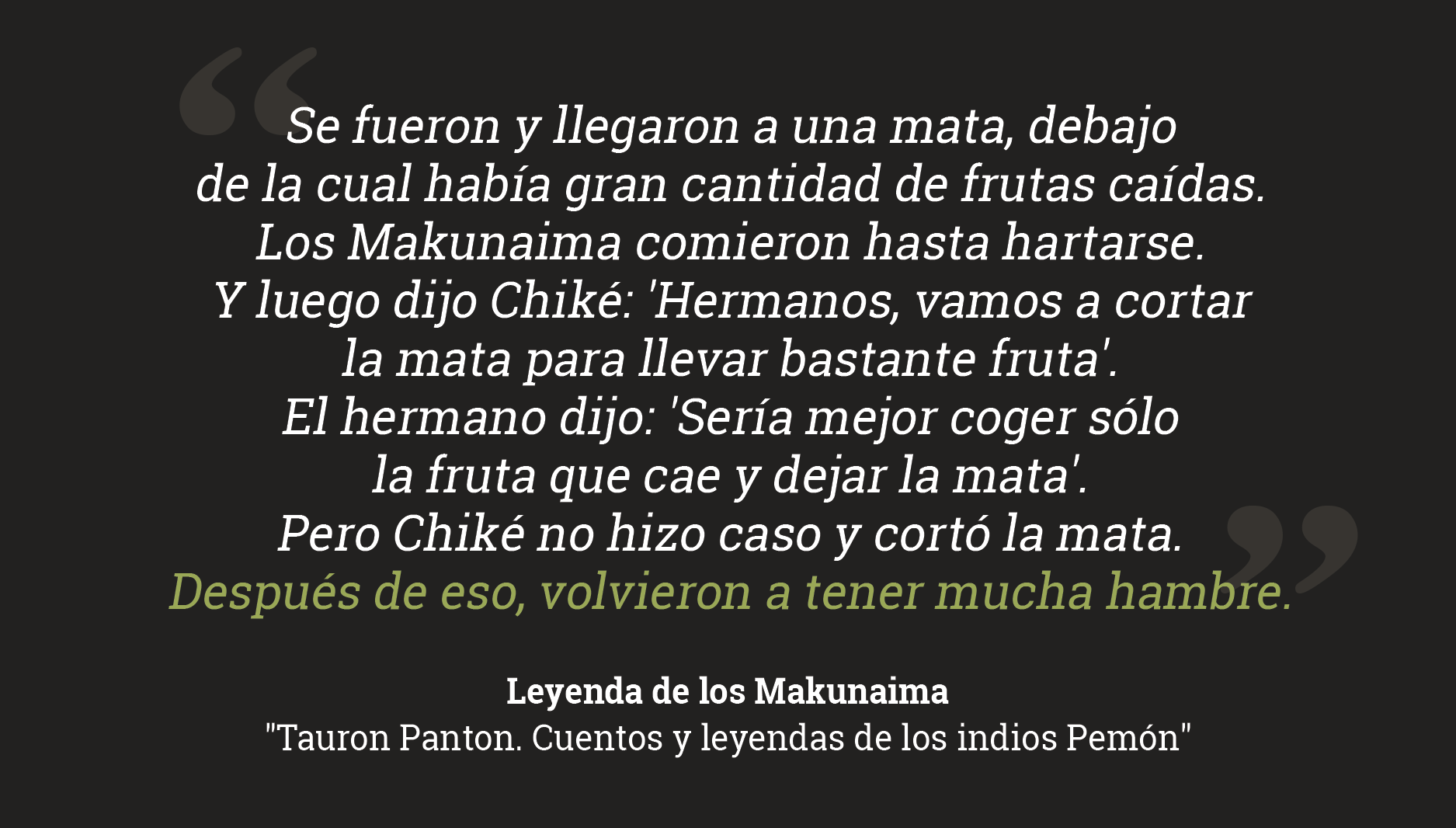

The only company Mr. Dias owns on paper is Transporte Aéreo del Sur, Transur C.A. where he appears to own 80% of the company’s shares. According to the Public Prosecutor’s Office, it is this company that links Dias with the gold smuggling network.

With the exception of Transur C.A., none of the other four properties he allegedly owns –Camp Uruyen, Camp Waká Vená, Gran Sabana Hotel, and Posada Mediterráneo- include his name in the records filed in the Mercantile Registries of Bolívar and Caracas. However, there are several elements that link Mr. Dias to the companies that own these properties. For example, Joseph Rodríguez Sousa, the president of Transur C.A., is also a shareholder of Camp Uruyen, set up in 2018. José Luis Hernández Santana and Claudio Alberto Monasterios González, are business associates of the company Posada Turística Ara Merú Lodge C.A. as well as Gran Sabana Hotel. Monasterios González is president of Paca Trading, a Panamanian corporation whose board of directors includes José Alberto Monasterios and María Concepción González Gómez. Ms. González Gómez is also one of the owners of Inversiones CLD 2012, C.A. (a corporation which owns 60% of Ara Merú Lodge shares) and at the same time is the director of CD Holdings, a corporation with headquarters in Panamá in which César Leonel Dias González serves as president and chairman. In turn, Fernando Tarazona, who serves as vice president of Transur, C.A., is signaled by the press to be the owner of Ara Merú Lodge, C.A.

As stated, Mr. Dias González is the alleged owner of Posada Mediterráneo, a beach lodge located in Los Roques archipelago, another national park. Opened in 2009, the lodge has received distinguished guests such as Venezuelan soccer player Tomás Rincón who celebrated his wedding there. Posada Mediterráneo is managed by Mr. Dias González’s sister, Alejandra Dias Dávila. In 2018, she was seen attending the International Tourism Fair (FITUR) held in Madrid, promoting her brother’s properties at Venezuela’s official stand.

Ms. Días Dávila, who also does public relations for Ara Merú Lodge, describes her older brother as “forward-thinking, a curious dreamer”. In an interview for Etiqueta magazine on August 13, 2017, in which César Dias is identified as the owner of the five star hotel, Ms. Días Dávila stated that “it all began with a dream my brother César had after falling in love with Canaima National Park when he visited it for the first time”. The hotel was inaugurated during the 2017 Carnival holidays and opened to the public in January 2018.

Actas Constitutivas de Ara ... by runrunesweb on Scribd

As reported by Los Roques Posada Mediterráneo’s Instagram account, Ara Merú Lodge’s was officially presented by Grupo Maloka at the 2016 Venezuelan International Tourism Fair (FITVEN) held at the island of Margarita in November of that year.

Purchases made prior to the opening of Ara Merú Lodge speak of the magnitude of the site. According to the Importgenius database, just in May 2016 the company imported 6.8 tons of merchandise equivalents to $75,753, distributed in furniture ($33,165), machinery ($20,748), rugs, glass and manufactured goods ($16,523).

Like stones under the river

Ara Merú Lodge’s development began way before its formal presentation at FITVEN in 2016. It was registered in the Mercantile Registry Office on July 3, 2013, four months after Nicolás Maduro took oath as President of Venezuela and a few months before the claims on mining in Canaima began.

The articles of incorporation and bylaws of Posada Turística Ara Merú Lodge, C.A. are one of the most guarded records in the II Mercantile Registry office in Ciudad Bolívar, capital of Bolívar state. Contrary to the principles of accessibility and free consultation of its archives, as established by the Venezuelan Law on Registries and Notaries, the file that contains the original records of this company in particular is jealously guarded. A request for this file in October 2019 was met with endless excuses about the computer system being down until finally public employees claimed that it had simply “disappeared”.

The articles of incorporation state that the company was registered with a capital of Bs. 2,000,000 which are equivalent to $198,020 according to the official exchange rate for the month of July 2013 (rate given by the Alternative Foreign Currency Exchange System ((SICAD for its acronym in Spanish)).

The shareholding structure of Posada Turística Ara Merú Lodge, C.A. is peculiar. The majority of the shares (60%) belong to Inversiones CLD 2012, C.A., a company registered in Los Teques which is located around 621 miles from Canaima National Park, where the headquarters of Ara Merú Lodge are based. The owner of Inversiones CLD 2012, C.A. (which bears the initials of César Leonel Dias) is Claudio Alberto Monasterios González, who in turn owns 51% of shares at the Gran Sabana Hotel and also votes in the same electoral center as Mr. Dias González.

The second main shareholder of Ara Merú Lodge is José Luis Hernández Santana who is also the owner of 9% of shares in the Gran Sabana Hotel. He also owns the company Orinoco Airlines headquartered in Hialeah, Florida, U.S.A.

The remaining Ara Merú Lodge shareholders are distributed as follows: 10% of the stocks are owned by Rosmary Eugenia Sulbarán Sulbarán and Darío Ramón González (both Pemón indigenous people) own 10% of the shares respectively while the remaining 5% of shares belong to Charlie Alexander Rivas Manrique (also a Pemón).

Golden Aircrafts

In a matter of six years, Mr. Días González has built a network of companies throughout several cities in Venezuela, the US, Panama and Colombia whose company objects range from construction materials, vehicle maintenance to tourism services.

In his August claim, Attorney General Saab stated that the parties involved were legal representatives of multiple related companies across Venezuela used as facades to launder money obtained from illicit operations. He also claimed that Mr. Dias González’s company Transporte Aéreo del Sur, Transur C.A. directly links him to the smuggling network as this company owns the light aircrafts which were used for trafficking operations. According to the Attorney General, Mr. Dias González used these aircrafts to fly multiple times to the Dominican Republic, Curacao, Aruba and Trinidad, the same islands that are part of the gold contraband route.

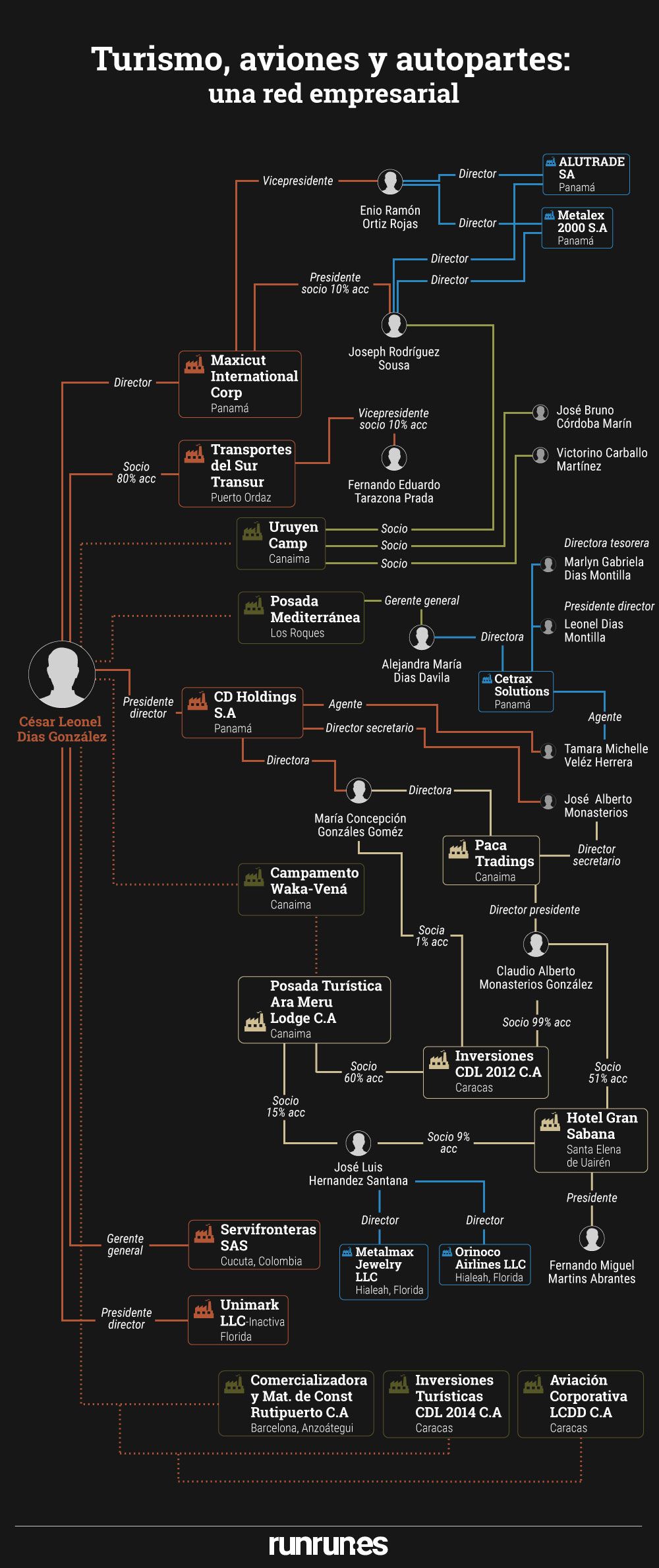

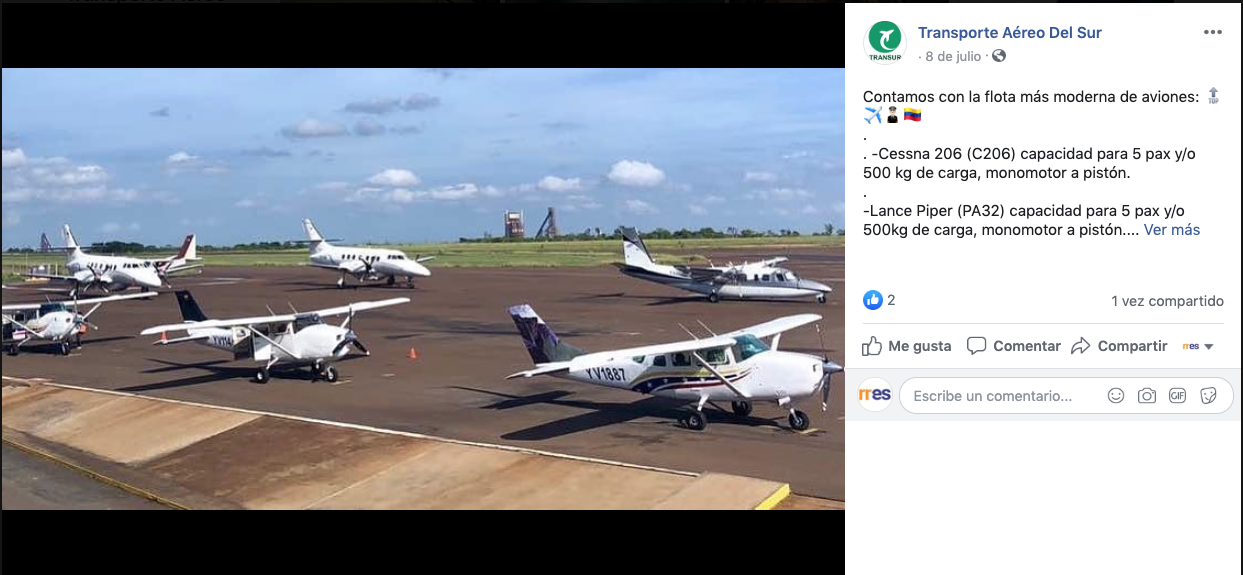

This post was published by Transportes Aéreos del Sur, Transur, C.A. on its Facebook page after Tarek William Saab accused its owner, César Dias, of being a member of a gold smuggling network. Photo: Facebook page screenshot.

This post was published by Transportes Aéreos del Sur, Transur, C.A. on its Facebook page after Tarek William Saab accused its owner, César Dias, of being a member of a gold smuggling network. Photo: Facebook page screenshot.

All planes owned by Transur, C.A. have the Ara Merú Lodge logo stamped in their fuselage. They were usually seen on the runways of Ciudad Bolívar and Puerto Ordaz airports, both of them in Bolívar state, chartering tourists to Canaima. However, in recent months, these aircrafts changed routes. A tourist operator confirmed that the Cessna 206 planes used by this airline had stopped flying tourists and began flying food, machinery and utensils to the mining zones instead.

Although Mr. Dias González owns 80% of Transur, C.A. shares, he is not on the company’s board of directors. In his place are Joseph Rodríguez Sousa as president and Fenando Eduardo Tarazona Prada as vice president. The three of them set up the company in Caracas in January 2019. Its original headquarters were located at Torre América, Av. Venezuela, Bello Monte, municipality of Baruta (Caracas) until they changed location to Manuel Carlos Piar International Airport in Puerto Ordaz, Bolívar.

According to its articles of incorporation, the company object of Transur, C.A. deals with “repair, installment, maintenance, implementation and installation of everything related to aircrafts, airplanes, import and sale of aeronautical parts as well as anything related to this matter including any type of transportation, including international and domestic freight transport, passenger transport, mail, executive transport, and affiliation to the Organization of Aeronautical Maintenance (OMA)”. The company also specializes in “trading, importing, exporting, buying, selling any type of materials, supplies, raw materials, equipment, and any related products and machinery”. Likewise, the company “(may) associate with other domestic or foreign companies to enter into any form of legal trading activity”.

Acta Constitutiva de Transur by runrunesweb on Scribd

The capital put forward to set up the airline company was Bs. 17,054,370 (equivalent to $5,175 according to the exchange rate registered that day by the Central Bank of Venezuela). The most expensive items in its inventory are nine computers, two air conditioners and two Kawasaki Mule vehicles. There are no aircrafts registered in the document. A used Cessna 206 airplane, such as the ones that make up the Transur fleet, cost around $200,000 in international markets.

Transur, C.A. succeeded a company called Corporación Aérea del Sur (Corasur for its acronym in Spanish). In September 2018, one of its light planes crashed into the Auyantepui killing four passengers (two adults and two children), all of them members of a single family and the pilot Ángel Larrode who according to El Cooperante had been suspended by the National Aeronautical Institute (INAC) for forging flight hours to obtain an additional accreditation.

The damaged aircraft was part a fleet belonging to Corasur which was certified through express service as an aerial taxi company by the INAC in 2018. According to regional sources, its owner, Fernando Tarazona, “the owner of Ara Merú Lodge” according to the press, had invested some $3,000,000 in the company’s facilities at Carlos Manuel Piar Airport in Puerto Ordaz.

Transur, C.A. has a Facebook page created on March 26, 2018. The Page Transparency section shows that the company changed its name one time from Corporación Aérea del Sur to Transporte Aéreo del Sur.

Another kind of tourism

César Dias González also has a company registered in Colombia, specifically in Cúcuta. Inversiones Servifrontera SAS was created on August 24th, 2015. Its registration certificate is currently inactive according to the registries located in the Cúcuta Chamber of Commerce. Mr. Dias González serves as the general manager of this company which specializes in, among others: “the maintenance and repair of automobiles, sales of new and used parts for automobiles and wholesale trade of solid, liquid, and gas fuel and connecting products”. Nothing is related to tourism.

One of the last known financial operations made by Mr. Dias González was the setting up of a corporation in Panama called CD Holdings S.A., on June 24th, 2019. According to the website Open Corporates, the businessman is the company’s director, president, treasurer, legal representative and executor. Only three more names appear in the corporation: José Alberto Monasterios (secretary, director and executor), María Concepción González Gómez (director) and Tamara Michelle Velez Herrera (agent).

Monasterios and González Gómez, are not only shareholders of Ara Merú Lodge, they are also business associates of Paca Trading S.A., another Panamanian corporation set up in December 2017.

The Open Corporates website also states that in November 2016, Mr. Dias González registered another company named Unimark LLC.in Sunrise, Florida, U.S.A. It is currently inactive.

Judging by Tarek William Saab’s August 16 accusation, the Maduro administration is fully aware of what gold smuggling means. Although Mr. Saab did not mention Canaima expressly, he did point out the havocs caused by illegal mining and trade. He classified it as a high degree criminal offense which hurts Venezuela’s economy and seeks to destroy it in “unimaginable levels”. He stated that “it is comparable to the worst crimes, a crime against humanity and drug trafficking. It is controlled by mobsters who disguise their criminal activity through companies that only exist on paper. It is a whip that hurts the people of Venezuela”.

But deep down all of these actions taken by the Maduro administration to fight gold trafficking do not seek to administer justice, preserve the environment or eradicate mining at the national park, says Congressman Américo de Grazia, a frequent critic of the mining management and its human rights violation in Bolívar.

“Perhaps, behind this Canaima businessman, accused today of gold trafficking there was another operator such as former Governor of Bolivar Francisco Rangel Gómez or the current Governor, Justo Noguera Pietri, all of them groups of power who pretend to displace others in order to control the mining business. The pattern of the Operation Metal Hands carried out in 2018 continues. There are no rules in the criminal market”, says Da Grazia.

Blood and the tepui

A military attack allegedly planned in a luxury lodge

“That’s where everything was orchestrated”, says a Pemón tour guide when reminiscing about the day in which for the first time Canaima felt the corrosive smell of tear gas and the bursts of gunfire. The place he is referring to is Ara Merú Lodge, a camp which according to the locals was built in a record period of two years and is described in travel reviews as the most modern and luxurious lodge in the area. This was also the lodging place of 20 officers of the General Directorate of Military Counterintelligence (DGCIM) who on December 8, 2018 entered the national park’s mining area and shot a Pemón indigenous man to death, wounding another two. This was known as “Operation Tepui Protector”.

Unlike other hotel lodges in the area of Kanaimó –the capital of Sector 2 in Pemón territory- Ara Merú Lodge is the only one surrounded by high shrubs. It has a single entry, giving it a greater sense of privacy in comparison to the others. In order to get in, one has to go through a stone arch covered by a water curtain, a sort of recreation of the nearby waterfalls. And unlike the others, it counts with a pool, a gym and a cement replica of Angel Falls.

Ara Merú Lodge is the most luxurious camp in the area. Photo: Lorena Meléndez G.

Ara Merú Lodge is the most luxurious camp in the area. Photo: Lorena Meléndez G.

The reason why these officers stayed at Ara Merú Lodge has always been noted by the residents of Kanaimó and Kamarata. They claim that this is where the military tends to stay when they travel to one of the most expensive tourist destinations in Venezuela (at a cost of around $600 per person). Only a fraction of the country’s population can stay here. In Venezuela more than 45% of its inhabitants eat less than three times a day according to market research companies such as Delphos and Consultores 21.

There is an additional key piece which has gone unmentioned. The owner of Ara Merú Lodge is César Leonel Dias González. He is wanted by the Venezuelan authorities since June 2018 when the government published a list of people linked to gold smuggling operations. His involvement in these operations has been known since August 2016, thanks to his relation with another company: Transporte Aéreo del Sur (Transur, C.A.) which, according to the Public Prosecutor’s Office, has smuggled the golden mineral to countries such as the Dominican Republic, Curacao and Aruba.

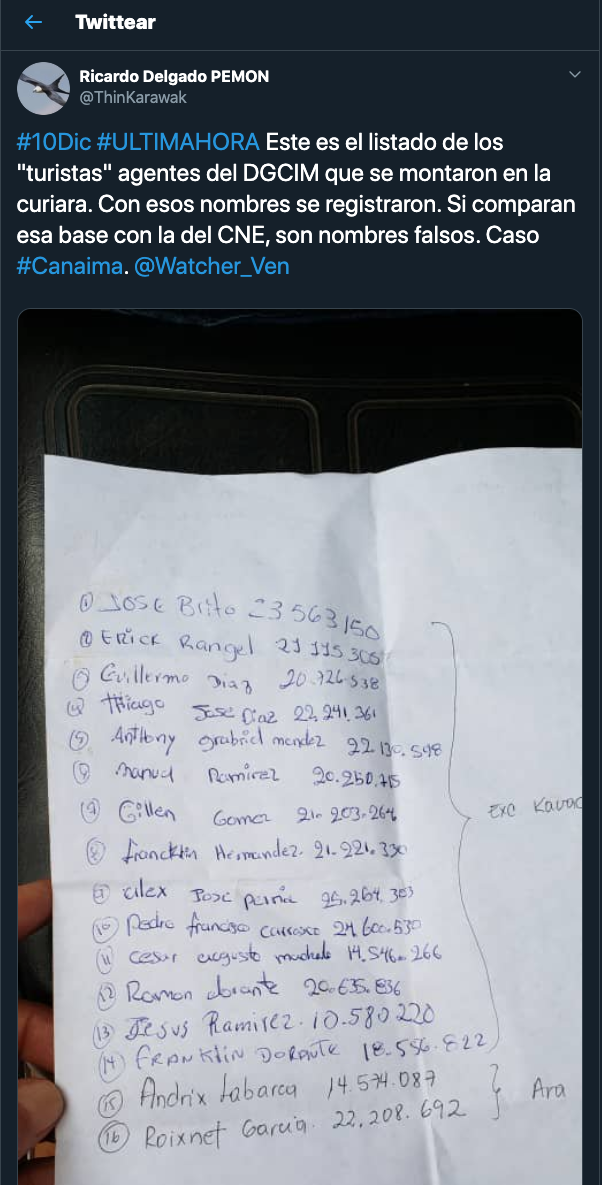

The DGCIM officers arrived at Kanaimó on December 7, a day before the attack of the indigenous miners. They registered with fake identities, passing off as tourists. Their weapons were secretly smuggled into the National Electric Corporation’s (CORPOELEC) facilities. Witnesses claim that the DGCIM officers celebrated their supposed holiday with whisky on the banks of Canaima Lagoon. At dawn, 18 of them climbed into two curiaras (dugouts) and went on an expedition along with a group of Pemón indigenous men who drove the boats and acted as tour guides. The plan was to reach Kerepakupai Vená, better known as Angel Falls. But this is not what happened.

The list of a used by DGCIM officers during the “Operation Tepui Protector” Photo: Ricardo Delgado.

The list of a used by DGCIM officers during the “Operation Tepui Protector” Photo: Ricardo Delgado.

En route through the Carrao River, and right before the dugouts steered into the Churún River which leads to the enormous waterfall, the undercover military officers seized control of the dugouts and the crew. “They kidnapped the men and gave orders to take them to the mining zone. They were armed up to their teeth (…) and had ranged weapons”, says Gregorio Rivas, owner of Morichal Camp in Canaima in an audio uploaded onto the Instagram account @CanaimaSeRespeta.

Arenal in Flames

A score of gunshots can be heard throughout the minute-long video taken by a man inside one the dugouts, its blasts echoing throughout the jungle. The image is shaky as he tries to point his cellphone towards the bow of the boat, catching glimpses of the mighty and dark Carrao River. In the background, the permanent noise of the motor’s engine mixes with the breeze hitting hard on the cell phone’s microphone. One of the crewmen yells: “Go, go”, while the black jacket of another fills up with air. Seconds later, only the rugged and damp walls of the wooden boat can be seen. Lifting one’s head in the middle of the gunfire is not safe. Thus begins one of the recordings of the “Operation Tepui Protector”.

At this precise moment, however, everything is confusion. Orders are given and caution is implored. “Hands up, hands up”, repeats a man who seems to be inside the large canoe. “Hold on, hold on… Careful, careful”, says another of the voices amidst the gunfire. The boat comes to a halt the engine is turned off.

Finally, the camera focuses on what is happening: the dugout has reached a makeshift barge. Standing there, are Pemón miners, wearing flip flops, shorts and sleeveless shirts. This is the same outfit worn by all of those who extract the golden metal around the Orinoco Mining Belt and by men in Canaima who speed through the Carrao River every day to get to the mines and open-air pits. Today is no exception, yet the atmosphere is different. The volley of gunfire does not cease.

The video’s description states that this was the moment when indigenous peoples defended themselves against an attack committed by “Criollos” –which is how this tribe refers to non-indigenous peoples- against Pemón miners working on the mines of the Arenal sector, near the Auyantepui tabletop where Angel Falls is located. According to several sources, there were many Pemón men carrying rifles and arrows during the attack. Yet only the indigenous men were wounded. One of them, a 21 year old man named Charly Peñaloza was fatally shot by a bullet. His brother, Carlos Peñaloza, 25, and César Sandoval were wounded.

Arenal is a sector of the Carrao River which used to be a mining area 60 years ago until Canaima was declared a national park and tourism became the main economic trade throughout the Gran Sabana Municipality. Today, amidst the economic and social debacle ravaging Venezuela, Arenal has gone back to its roots. Wooden rafts used for mining float by on the banks that face the Wei Tepui. All of them possess a hose used to dredge the river’s sand in search for gold. These form sediment banks which pull through the surface and have to be dodged by boatmen during their navigation on the river. Tourist camps nearby are filled with hammocks belonging to local miners. Even the nightly concert of frogs, toads, birds and insects which begins at sundown has to compete with the buzzing noise of water pumps and the constant presence of indigenous men seeking for the precious metal in the banks of the Carrao River.

When the DGCIM arrived at Arenal, the miners where changing work shifts, says Carlos Somera, delegate of the Commission of Inter-Institutional Alliance ascribed to the Council of General Caciques of the Pemón Peoples. Mr. Somera led the investigations of this case. According to him, the miners working the night shift had just left when the DGCIM arrived, pointed their guns to the morning shift workers, told them about the operation and ordered them to abandon the site immediately. The Pemón men reacted to the situation.

“Our brothers confronted the men verbally”, explains Mr. Somera, also an indigenous man, who insists that none of the Pemón had weapons on them at the time. He claims they approached the officers, demanding explanations and hoping to prevent any damage to the barges. Instead, they received a shower of bullets which wounded three of them on the legs.

At that moment, the Pemón made an unexpected move. Several of them dived into the Carrao River and surprised two officers standing on a raft from behind by pushing them into the water.

According to Mr. Somera, one of the DGCIM who fell almost drowned while the other was immobilized when they took his knife and pointed it to his neck. In the end, the Pemón defeated the officers by taking several of them as hostages. The majority of the officers escaped through a nearby brook. They were presumably rescued at a later time by aerial means.

Several Pemón men who were present during the incident claim that the operation was much more violent. “They (the DGCIM) arrived on a dugout. On the other side, where that stone slab is, was a helicopter belonging to CADAFE (the region’s former electric company) who shot my brothers”, says a Pemón man while signaling the rocky formation that stands out from the borders of the river and which served that morning as an improvised helicopter landing spot. He also points out to the location in front of the slab where his “brothers” –among them women and children- ran off to take shelter in the depths of the jungle.

The recorded testimony of Carlos Peñaloza, one of the wounded men, coincides with this last version and reconstructs part of the situation taken place at Arenal. Lying on a hospital bed, he described in Pemón language what had happened the day after he got shot:

“There were 14 to 20 men. My brother and I approached them confidently and we got shot. After that, my other “brothers” (Pemón indigenous people) got upset and the rebels called a helicopter and our men forced the rebels to land the helicopter under one condition”, he says.

He aquí el testimonio de Carlos Peñaloza,pemon sobreviviente al ataque del DGCIM donde desmiente la presencia de otros armados que no sean los funcionarios del Régimen,capitaneados por Alexander Granko (DGCIM)el mismo que asesinó a Óscar Perez.(idioma pemon)traducción en el hilo. pic.twitter.com/8jFcBA7X0U

— Americo De Grazia (@AmericoDeGrazia) December 9, 2018

That condition was to free the officers detained by the indigenous people in Arenal. Peñaloza calls the DGCIM “rebels” because during the first hours, the Pemón men thought that the attack had been led by the mafia groups who are usually behind the business of Venezuelan gold: armed gangs or the guerrilla.

The aforementioned helicopter also flew by Campo Carrao, the open-air pit which is a few miles from the mouth of the Akanan River, north of the Auyantepui. This is the place where indigenous men board the boats that take them to the mines. The helicopter landed there and dynamited the entire airstrip but its occupants were detained by the Pemón miners who happened to be working there at that moment.

At the time of the ongoing shoot-out, a mass ceremony in the small stone and cement chapel at Kanaimó had just begun. It was December 8, and the villagers were celebrating the day of the Virgin of the Immaculate Conception, their patron saint. When the choir was singing the Marian hymns, the ceremony was interrupted by the arrival of the Pemón men who were wounded in the mining zone. Charly Peñaloza died a few hours later after being taken to Puerto Ordaz. It was 8:00 in the morning.

The Church of Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception. Churchgoers where gathered here when the undercover military attack in Arenal occurred. Photo: Lisseth Boon.

The Church of Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception. Churchgoers where gathered here when the undercover military attack in Arenal occurred. Photo: Lisseth Boon.

By mid-afternoon, the officers returned for the miners who had escaped. They threw tear gas at the villagers. Most of them recorded videos which they uploaded to their social networks to alert the situation. And although news became viral throughout the country, indigenous leaders confiscated all of the evidence later on. Today, this evidence is in the possession of Domingo Castro, the General Cacique of Sector II, who refuses to comment on the incident.

“This is a matter which our community has tried to make up for, not dwell upon. In consideration, I feel that talking about this again is not wise. It is a high-profile topic and I’ve been working hard so that this painful moment that we lived as a community and the fear my brothers felt at the time remain solely as a bloody chapter in our history which will never happen again”, he responded to Runrun.es via a WhatsApp message.

Mr. Somera is certain that the DGCIM had chosen the date of the Patron Saint to attack because they believed that the entire Pemón community would attend the church celebrations that morning and that only Brazilian miners –the operation’s alleged target- would be at the mines. When they arrived there, only the Pemón miners were to be found. Even today, the “Criollos” are not welcome in the mining area.

The story that played out in the Venezuelan digital media differed from the actual events. Although they later corrected by saying that the officers had entered the territory in a violent manner and shot against the aboriginals, the first headlines stated that there had been a confrontation in Canaima between the Pemón People and the DGICIM, resulting in the death of an indigenous man.

El Universal and 2001 reported the incident as a confrontation.

El Universal and 2001 reported the incident as a confrontation.

This version was backed up by the Minister of Defense Vladimir Padrino López who finally addressed the Arenal military attack on December 11, 2018. Joined by Remigio Ceballos Ichaso, Commander General of the Army, Padrino López ratified that the operation was part of a plan entitled “Tepui Protector”, an operation created by the Maduro administration to end mining inside Canaima National Park.

“There was a confrontation, there were weapons involved, and they aimed against this commission (…) and the result of this exchange, of this confrontation in the area was four men wounded with firearms. Regretfully, one of the four died and we deeply condemn this action from the bottom of our heart”, explained Padrino López in a televised address without mentioning that the victims were members of the Pemón tribe. He later stated that the DGCIM officers were evacuated from the site, although three of them were still held under custody by the indigenous men. He also said that the wounded were quickly taken to a hospital in Ciudad Bolívar, capital of Bolivar, contradicting Congressman Americo Da Grazia’s claim that they had been taken to several other medical dispensaries before being taken to the hospital.

In this same address, Padrino López assured that several makeshift barges were destroyed during the operation and he pointed the blame towards “international mafias” with economic power who were seeking to turn indigenous people against the government.

The Minister of Defense’s affirmations got an immediate response from the indigenous people of Canaima. In a public statement endorsed by the General Council of Caciques, they denied the confrontation Padrino López had referred to and questioned that he addressed the issue four days after the incidents. They called him a coward, a colonizer, thief, cynical, liar, ignorant, a charlatan and a murderer.

Lucy Rossy, Secretary General of the General Council of Caciques reads the statement.

“You plead for dialogue and justify this operation with basis on the Constitution. Isn’t murdering an indigenous man in a military operation a violation of the Constitution? Does a military operation constitute dialogue? (…) Who mistreated the indigenous people and who took away their belongings? (…) You must resign. The Bolivarian Armed Forces are the protector of its people, not its henchman nor its murderer”, said Lucy Rossy, secretary of the Council in a statement read at a press conference which went viral.

Pemón Jurisdiction

Hours after the attack, the indigenous people had taken actions to condemn the incidents. The Council of General Caciques had declared seven days of mourning throughout the Gran Sabana Municipality, suspended elections for city councilors in its jurisdiction –these elections were set to be held throughout Venezuela on December 9 -, announced an indefinite stoppage in all the communities within the area, and closed ports, airports and roads. They also held the State accountable for the events and demanded an investigation on Peñaloza’s death as well as an explanation as to why was he transferred from a private clinic to a public hospital.

While they were making the aforementioned statement, the Pemón people were interrogating the alleged perpetrators: the two DGCIM officers who were caught at Campo Carrao and an additional officer that the Bolivarian National Guard had under its custody at Kanaimó. Up to this moment, they ignored that they were undercover military men, as they thought they were members of the militia or the guerrilla.

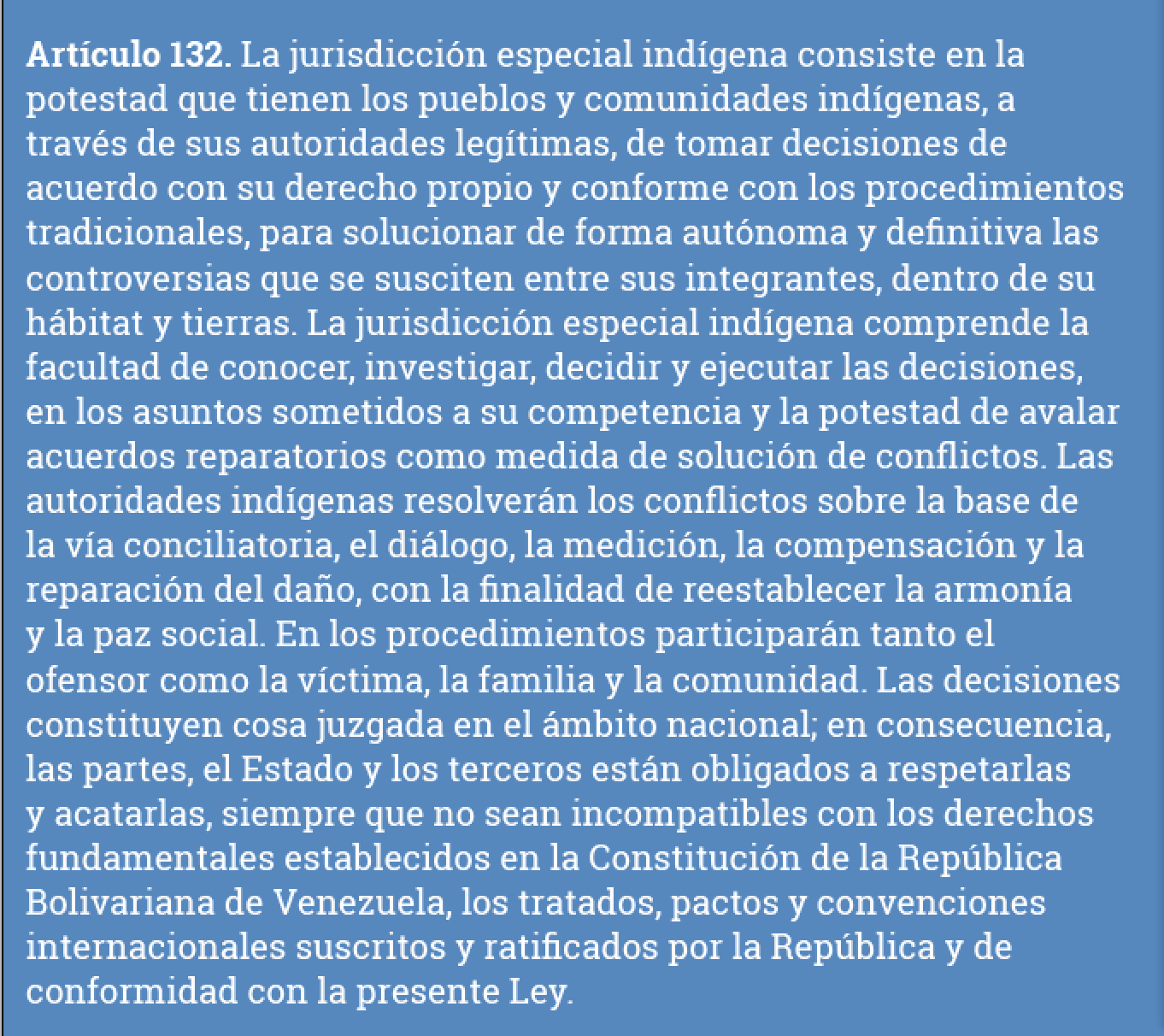

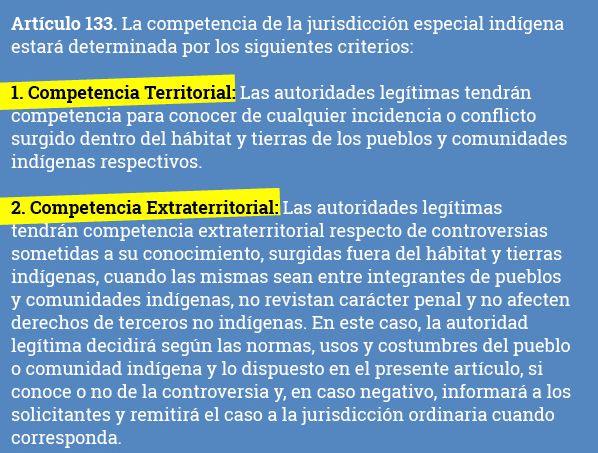

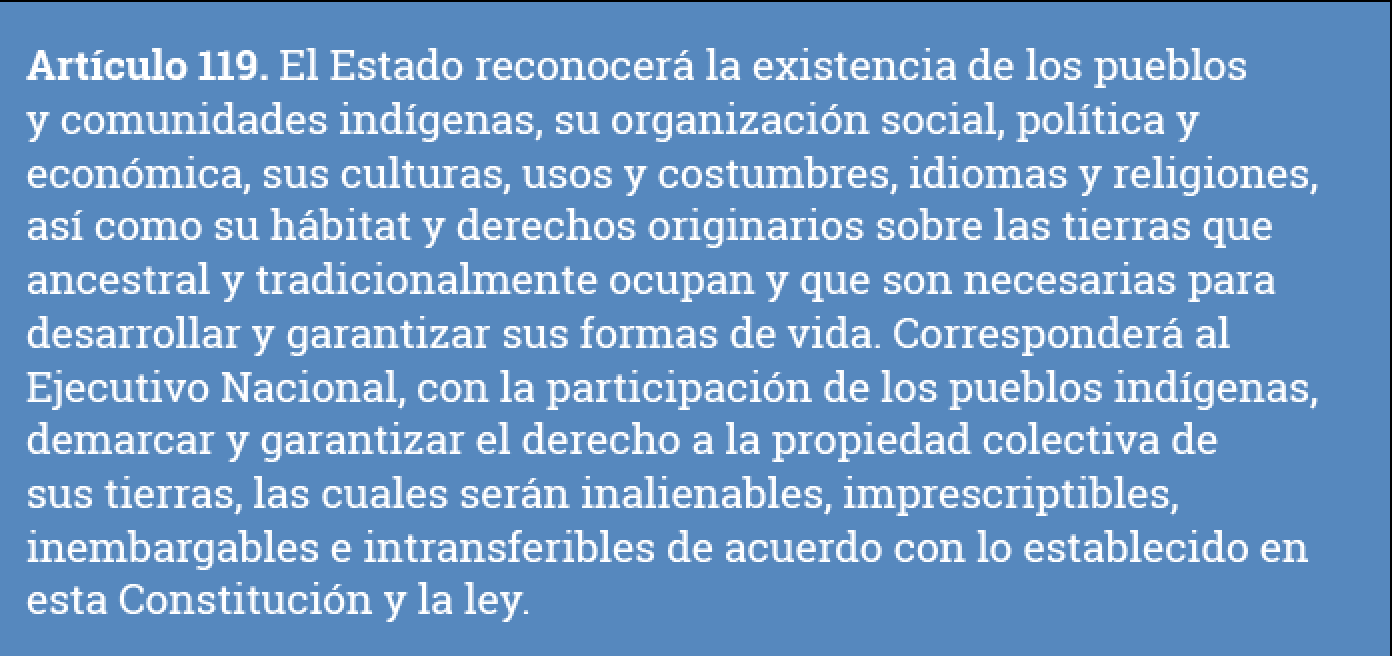

The decision to interrogate them was based on the application of special indigenous jurisdiction, a legal provision contained under the Organic Law of Indigenous Peoples and Communities, which grants them the power to solve all conflicts generated in their territory in an autonomous manner.

The special indigenous jurisdiction became active on December 10, 2018 two days after the Arenal events. This was established in the “Preliminary Report by the General Council of Caciques of the Pemón People on the armed attack in Canaima”, which declared the opening of the case with the testimonies of eyewitnesses, the integration of a commission which would verify the events on site and search warrants in Ara Merú Lodge (where the military men stayed) and the National Electric Corporation (CORPOELEC) in whose heliport the aircrafts carrying the agents landed. Likewise, the Pemón people decided to revoke the custody of the suspect to the Bolivarian National Guard in order to question him and arrested two workers from the electric industry identified as Édgar Velásquez and Luis Malpica. The case would be trialed and sentenced by the indigenous people and notifications of this action were sent to the Ombudsman’s Office.

The following day another public statement was issued, this time announcing blames. The Council of Caciques held the Maduro administration responsible for the “undercover military style operation” which looked to “render the Carrao River miners equipment unusable” and left one man dead and two wounded “with weapons belonging to the Republic”.

The statement also accused several DGCIM officers of being masterminds of the operation. Among them, its director the General Iván Hernández Dala; Major Alexander Granko Arteaga, Commander of the Special Affairs Unit; and Major Rafael Antonio Franco Quintero, director of Investigations at DGCIM. All of these men have been sanctioned by the government of the United States following the death of Captain Rafael Acosta Arévalo, presumably murdered according to his family and attorneys in June 2019 after being tortured while he was detained. According to the public statement, the military men plotted the operation together with “21 troop members and explosive expert officials” with the complicity of the then Minister of Electric Energy, Luis Motta Domínguez, who facilitated the use of CORPOELEC’s headquarters and aircrafts in Kanaimó, as well as the Bolivarian National Guard.

The indigenous special jurisdiction has also allowed the Pemón people to take measures in regard to every “Criollo” who enter Canaima. Nowadays, any person entering the park must submit to a mandatory luggage check. Local mistrust avoids referral to the Arenal events. According to guides, tourist expeditions through gold mining areas of the Carrao River must be approved by the miners who work there. Military immersion in Canaima has created rivalries and resentments. The “Tepui Protector” operation proved to be the exact opposite of what its name entails: it managed to make the aboriginals feel as vulnerable as they feel jealous about their territory.

Although the events in Canaima were widely spread in the news, only two indigenous communities from Sector 2 publicly condemned the incident. One of these communities was Urimán, where mining has been practiced openly for decades. One of its members reiterated that his people would not give up even a foot of their lands.

The other community was Kumarakapay (San Fransico de Yuruaní) where the former major of Gran Sabana, Ricardo Delgado, went on camera to express his support to his fellow countrymen in Kanaimó. “(These) are clear actions that the Government is taking to evict us from the mining zones”, he stated on December 8. Ten days later, the former public officer read a letter in Pacaraima, Brazil where he denounced the military operation and its consequences in the UNHCR humanitarian camp, set up in that city to aid Venezuelan immigrants. Incidentally, Kumarakapay was the scene of an incident occurred on February 22, 2019 when Army officers attacked indigenous people in the area who were expecting the entry of humanitarian aid announced by the leader of the National Assembly and interim President of Venezuela, Juan Guaidó. On that day, the smell of tear gas was felt again in the land of the tabletop mountains. Four members of the Pemón tribe were gunned down.

En el documento, explican que su acudida a instancias internacionales (en este caso ACNUR servirá de enlace ante la ONU) se debe a la ausencia del Estado de Derecho en #Venezuela. pic.twitter.com/ZommCARqGX

— Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde (@DrJ_y_MrH) December 18, 2018

A silent plan

Months before the armed attack, the Maduro administration met on several occasions with the Council of Caciques to discuss mining operations in Canaima as well as the plans needed in order to get indigenous miners to abandon the illegal activity.

Although claims of mining in the national park go as far back as 2011, the first land and machinery movements were registered in 2018 when several organizations began to echo the environmental hazard going on in a World Heritage Site. In July 2018, the NGO S.O.S. Orinoco published an extensive report on mining activities in the area. Amnesty International issued a statement against the accusations that the Brigadier General Roberto González Cárdenas had given where he accused the Pemón activist Lisa Henrito of leading a secessionist movement in Southern Venezuela when in reality she had only denounced illegal mining in Bolívar.

A 49kms del Parque Nacional #Canaima Patrimonio de la Humanidad @unescowhc, mineros ilegales devastan el Rio Supamo con #Mercurio, #cianuro y otros contaminantes, mientras #FANB y @CAMIMPEG_FANB se benefician y son cómplices de la destrucción. https://t.co/FXgGjkxHyQ #SOSOrinoco pic.twitter.com/1kHjFDAnlF

— SOS Orinoco (@SOSOrinoco) March 4, 2018

The first of these meetings regarding illegal mining between the government and indigenous leaders took place on October 5, 2018. According to several publications on official Twitter accounts, Remigio Ceballos Ichaso, the highest authority of the Operational Strategic Command of the Bolivarian Armed Forces (CEOFANB); the Minister of Culture, Ernesto Villegas Poljak; the Minister of Indigenous People, Aloha Nuñez; the Minister of Eco Socialism (formerly Environment), Heryck Rangel; and the Minister of Ecological Mining, Victor Cano, sat down with the Caciques to discuss protection measures for the park. “Integrating winning”, said a message published by CEOFANB on its social media, on occasion of that meeting.

En Parque Nac Canaima, Cmdte @ceofanb AJ @CeballosIchaso, Min @VillegasPoljak, Min @AlohaNueez y Min @vcano75 se reúnen con representantes de Etnia Pemon, para temas inherentes a la protección del Parque Nac y acciones para atacar la minería ilegal. “Integrar es vencer” pic.twitter.com/lCpmMAssra

— CEOFANB (@ceofanb) October 6, 2018

However, a source present at that meeting claims that the government’s real intention was either to provide the Pemón with equipment to continue mining operations or incentive them to work in the area’s lumber industry. The latter had been tried in the Sierra Imataca region which covers part of Northern Bolívar and Southern Delta Amacuro. According to this source, there was never any real intention of putting an end to mining.

The following day, the Pemón people went to a meeting with the Minister of Tourism, Stella Lugo, who visited the national park to inspect Venetur Canaima, a State owned vacation lodge which had recently undergone renovations. Lugo taped an interview there for a television program broadcasted by the State owned Venezolana de Televisión (VTV), in which she announced that Venezuela would participate in the World Travel Market trade show in London. “This is a unique tourist destination. The world is born here. The kindness of its inhabitants is evident in this place and they use their culture to enamor tourists”, she said in the interview. However, she never mentioned a word in public about her conversations with the Pemón indigenous peoples.

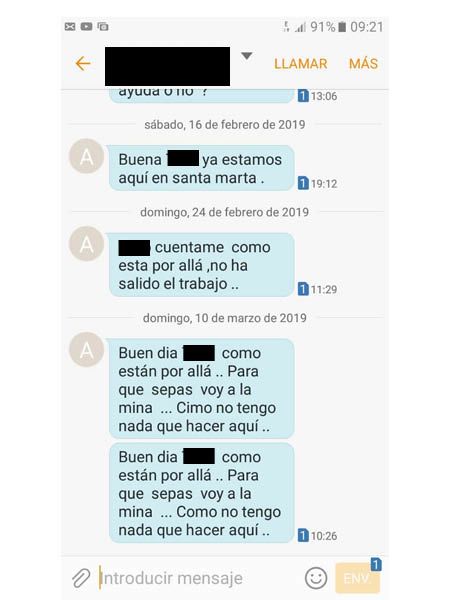

A source claimed that Lugo promised to reactivate tourism in the area. One of the measures she promised was the establishment of an aerial route between Puerto Ordaz and Canaima to be flown by Conviasa Airlines. Until mid-July 2019, not a single airplane of this State-owned company has landed in the area.

Venezuela es tierra de gracia. Desde Canaima, lugar donde nace el mundo, estuvimos inspeccionando las instalaciones del Campamento Venetur Canaima, que en los próximos días abre sus puertas para recibir a nuestros visitantes como nos los ha pedido el Pdte @NicolasMaduro pic.twitter.com/xBSCNjO4Kx

— Stella Marina Lugo Betancourt (@StellaLugoB) October 2, 2018

On October 8, 2018 the indigenous peoples began protesting against the violation of their lands claiming that illegal miners were extracting gold in Southern Bolívar. 10 days of continuous protests followed. Some of the actions they took involved closing a sector of an important trunk road (Kilómetro 67, Troncal 10). This road crosses the mining area and connects the Gran Sabana region (part of Canaima National Park) with Brazil. 22 communities belonging to different ethnic groups joined the protest, demanding provisions of food, domestic gas, fuel and price control on necessity goods. “We are not miners and yet they charge our food in grams of gold”, said one of the protesters to the Correo del Caroní.

Amidst the protests, Valentina Quintero, a journalist specialized in tourism, uploaded photos and videos on her social media that showed mining activates inside the national park. She mentioned the ministers of Eco Socialism, Mining Development and Tourism and demanded that they take action on this depredation of the environment. “There is no mining without fuel. The military controls gas in every border state. You know that better than we do. Get mining out of PNCanaima”, she wrote in one of her tweets.

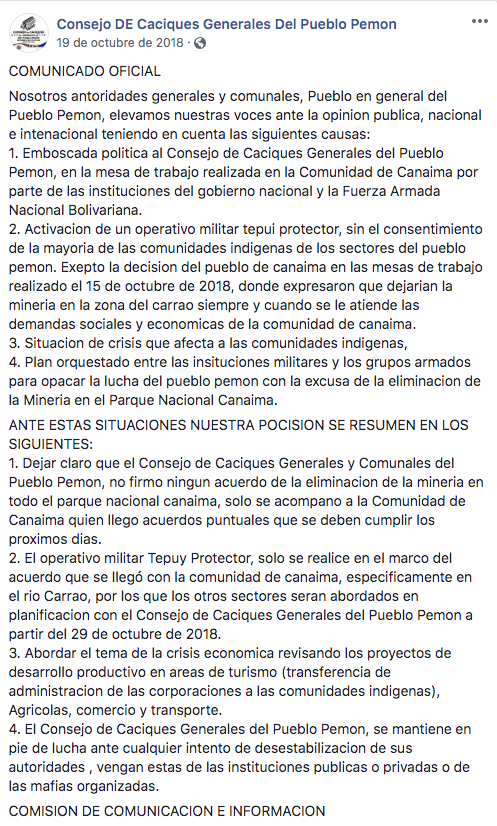

On October 15, 2018 the Vice Minister of Prevention and Citizen Security, Endes Palencia, confirmed the launch of Operation “Tepui Protector 2018” a plan involving civilians and the military to put an end to mining inside the national park. This announcement led to a statement from the Council of General Caciques of the Pemón Peoples who deemed that this measure was a “political ambush” to their organization.

According to the Council, “Operation Tepui Protector” was a “plan orchestrated between military institutions and armed groups to undermine the struggle of the Pemón People with the excuse of eradicating mining in Canaima National Park”. The statement made it clear that the Council of General Caciques of the Pemón Peoples had never signed an agreement regarding the elimination of mining across Canaima National Park as they had only endorsed the agreements reached by the community of Canaima. Therefore, the military operation “Tepui Protector” could only be carried out within the framework of the agreements reached by the community of Canaima, specifically in the Carrao River.

On October 31, 2918 the former vice president of “La Salle Natural Sciences Foundation”, Professor Ismael Fernández Díaz, filed a claim in the General Prosecutor’s Office against illegal mining in Canaima National Park. The claim, which includes coordinates of the areas where illegal mining occurs, stated the following: This not only hinders the V Object of the Nation’s Plan 2013-2019 which reads: ‘To preserve life in the planet and save the human species’, it also affects the lives of our fellow countrymen, our children, grandchildren and future generations. If this illegal environmental degradation continues in Canaima National Park, then other complex and already compromised ecosystems will inevitably disappear”.

In his claim, Professor Fernández Díaz also requested that an investigation be opened with the participation of the “Strategic Operational Commander of the Venezuelan National Armed Forces”.

Denuncia de minería en Cana... by runrunesweb on Scribd

Fernández Díaz also claimed that illegal mining activity in the Gran Sabana sector had been promoted and endorsed by the then Mayor Emilio González. A member of the opposition to the Maduro administration, González had condemned being persecuted by the Governor of Bolívar, Justo Noguera, since mid-2018. These claims worsened with the February 2019 military attacks to the indigenous peoples of Kumarakapay for their efforts to get humanitarian aid into Venezuela, which forced González to flee the country. The Governor of Bolívar removed him from office in April 2019, unilaterally selecting former Chavista congresswoman Nancy Ascencio to occupy his post.

Another meeting occurred on November 30, 2018 at the Venezuelan Chancellery. The Ministers of Foreign Affairs, Health, Eco Socialism, Mining Development and several other public officers such as the Attorney General, met with captains of the Pemón peoples to discuss the consequences of illegal mining inside the national park. The highlight of this meeting was a project entitled “A mercury-free Canaima”, led by the office of Jorge Rodríguez, at the time the Minister of Foreign Affairs.

Weeks prior to this meeting, this same plan had taken scientists to indigenous camps to pick up samples of river water in Canaima and test the degree of mercury contamination. On that 30th day of November, after presentations on the effects of mining in the environment, proliferation of malaria, the risks and diseases caused by mercury poisoning, the weak situation of public health in Bolivar and the mobility difficulty of the indigenous communities in Kanaimó due to the rising fuel costs, a decision was taken to request the activation of the “Operation Tepui Protector” against mining operations in the area.

“The militarization of the indigenous people represents a very delicate matter in the international law of indigenous people. It is extremely codified and everything requires a protocol. The way in which it was done is a violation of international protocols”, says Vladimir Aguilar, an attorney on indigenous affairs and coordinator of the Work Group on Indigenous Affairs (GTAI for its acronym in Spanish) at Los Andes University.

Two international treaties ratified by Venezuela establish the protection of aboriginal lands. One of them is the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention (C169) by the International Labour Organization which states under Article 18 that adequate penalties shall be established by law for unauthorized intrusion upon these lands. The other is the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples which states under Article 30 that military operations shall not take place in the lands or territories of indigenous peoples, unless justified by a relevant public interest. Or otherwise freely agreed with or requested by the indigenous peoples concerned.

“States shall undertake effective consultations with the indigenous peoples concerned, through appropriate procedures and in particular through their representative institutions, prior to using their lands or territories for military operations”, says a part of the article.

Eight days after the meeting in Chancellery, and even though the agreement had been to detain illegal miners and seize their belongings, Charly Peñaloza was killed in an undercover operation

The caciques go after the gold

Indigenous leaders support mining in Canaima

One after the other, the statements released by the Council of General Caciques of the Pemón Peoples, became the logbook of the events that followed the armed attack in Canaima on December 8, 2018. In these statements, the indigenous people condensed all claims, accusations and declarations given by their captains. These written and recorded manifestos lambasted the assault and gave notice of the steps taken to clarify the events as well as hold the State accountable for its actions. The State had just murdered one of their own kind; a young miner who was extracting gold at Arenal, an area not far from the Auyantepui and the Kerepakupai Vená or Angel Falls.

Members of the Pemón community protest against Nicolás Maduro and Vladimir Padrino López

This same fervor was not observed two months later, in the early morning of February 22, 2019, when military officers attacked the community of Kumarakapay in the Gran Sabana (the Western sector of Canaima National Park) for having rebelled and joined efforts to allow the entry of humanitarian aid through the Brazil border, an initiative called for by the government of Juan Guaidó.

A day earlier, indigenous leaders had published a letter in which they took no responsibility over any protest related to the humanitarian aid. However, they allowed their fellowmen to join the protest if they so desired. An extract of this letter reads as follows:

On that February day when uniformed guards shot three indigenous men to death and wounded thirteen others, not a single statement condemning this action was issued by the Council of General Caciques. Only complete silence.

According to several Pemón indigenous people interviewed in Kamarata and Kanaimó, the disparity in the reactions showed between the Canaima and the Kumarakapay events have to do with the existing complicity between the General Caciques and those who have to do with the mining business inside the park. “As long as indigenous leaders can do funny business with higher authorities, this problem will see no end”, says a tour guide who has witnessed how the tourism decline in the last few years has favored the exploitation of the golden metal with the blessing of indigenous leaders.

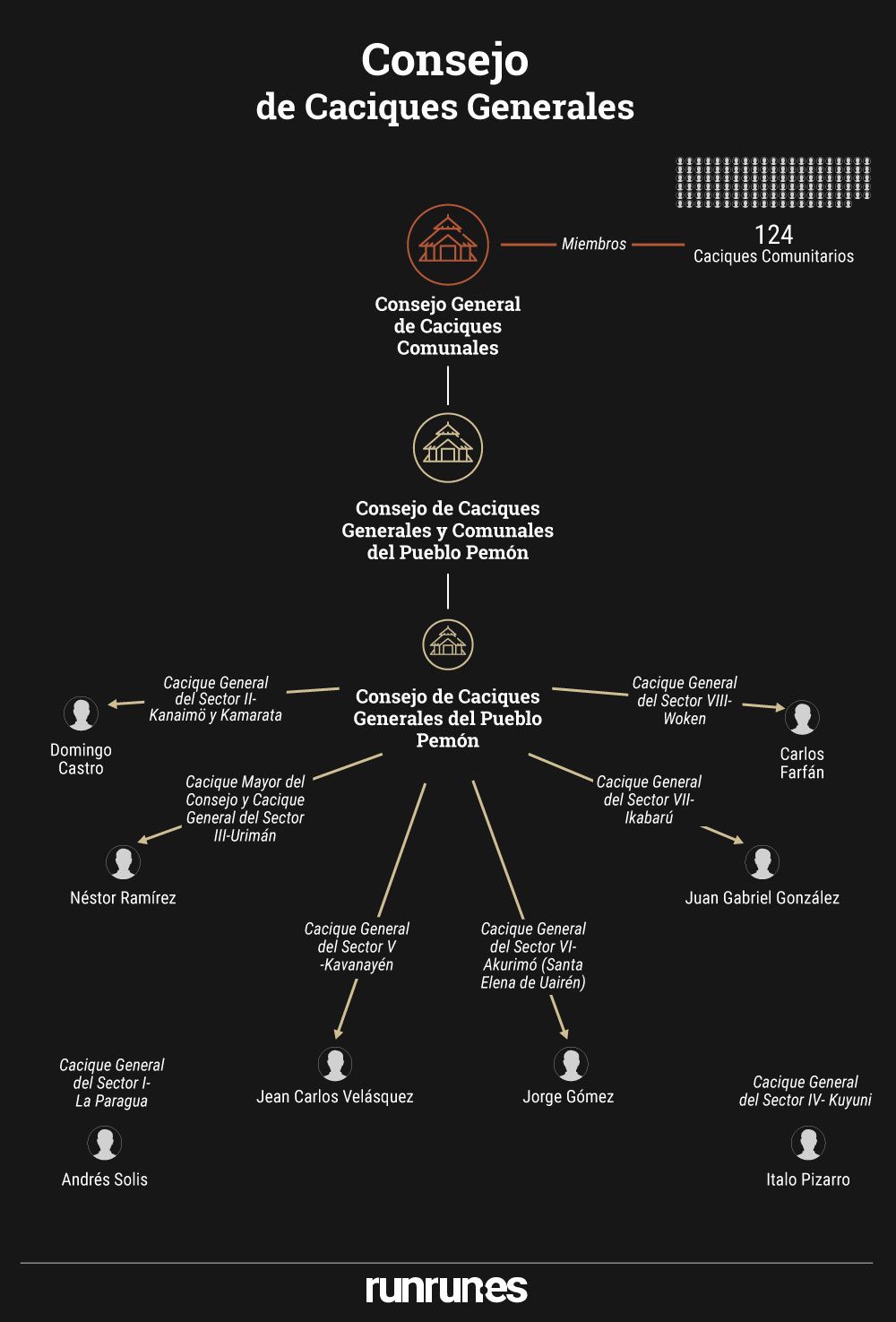

This blessing seems to have no direct relation to the group’s mission. The Council of General Caciques is composed by six captains that represent six of the eight areas in Pemón territory. 124 communitarian captains act as representatives of each indigenous community in the council. According to their official blog, the council’s object is to: “fight for the restitution of indigenous rights established in the Constitution of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela and execute its policy contemplated in the Organic Law of Indigenous Peoples and Communities”.

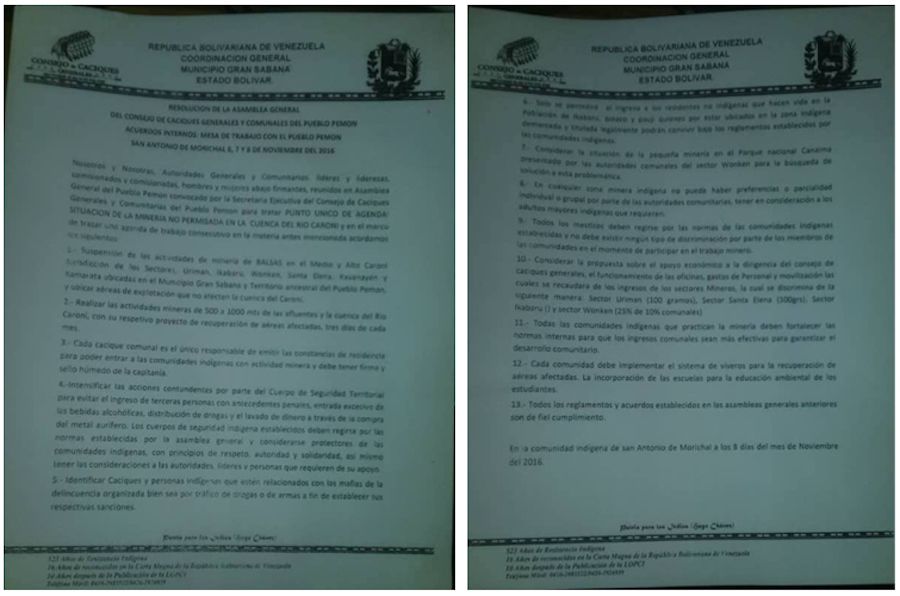

The Pemón indigenous leaders and their relation to mining activity has been evident if we take into consideration the decisions adopted by this council. On November 6-8, 2016, the General Assembly (comprised by the Council of General and Communal Caciques of the Pemón Peoples) convened at the indigenous town of San Antonio Morichal, located at a short distance from the Brazil border, to discuss the “situation of unpermitted mining on the basin of the Caroni River”.

The first thing the General Assembly agreed to in their resolution was the suspension of rafts used for mining in Middle and Upper Caroní River, which is within the jurisdiction of the sectors Ikabaraú, Urimán, Wonken, Santa Elena, Kanavayén and Kamarata. The Carrao River is located in Kamarata where gold is mined on makeshift barges which have not moved from there at any time. On the contrary, they have multiplied. The Arenal camp which borders this river is where the December 2018 military attack occurred.

Although the Council condemned mining on rivers, they did not do so with open air-pits like Campo Carrao, even though it is located inside the Caroní Basin and its sands and mercury are dumped directly into the Caroní River. In this case, the General Assembly established that all mining activities should be conducted at least 1,640 to 3,280 feet away from the tributaries of the second largest river in Venezuela.

Besides emphasizing the need to avoid the entry of third parties or indigenous peoples who could be associated with “mafias” to the mines, the resolution insists on royalties for the Pemón leaders

Besides emphasizing the need to avoid the entry of third parties or indigenous peoples who could be associated with “mafias” to the mines, the resolution insists on royalties for the Pemón leaders

Carlos Somera, delegate of the Council’s Institutional Alliance commission, confirms the veracity of this resolution but warns that leaders do not receive any royalties from the allocation of these fees. “This should be the norm and yet it is rarely complied with. The ultimate beneficiaries are the people”, he assures Runrun.es on a phone interview as he laughs in a brief and sarcastic manner.

The people do profit according to clause 11 of the Council’s resolution. Indigenous communities are in charge of ensuring that the income obtained through mining be “more effective in order to guarantee collective development”. Incidentally, every community is commanded by a Cacique.

Despite the endorsement of mining operations, the same resolution calls for implementation of greenhouse systems to recover areas affected by gold extraction and that the subject of “environmental education” be taught at local schools. However, parents in Kamarata, Kanaimó and Kavac report that their children wish to work in the mines when they grow up. In Arenal, Pemón adults take their offspring to work on the mining barges.

The matter of royalties had already been discussed between the general and communal Caciques in a meeting held in June 2016 in Santa Elena de Uairén. In this meeting they proposed the creation of an “Economic Commission” which would be “under the directory of the Fund for the Development of the Pemón Peoples”, and whose income would be based on the earnings brought in by tourism, agriculture, trade and, of course, mining. The commission would also be responsible for the creation of social programs, investments and the promotion of manufacturing companies which would generate revenues for the fund.

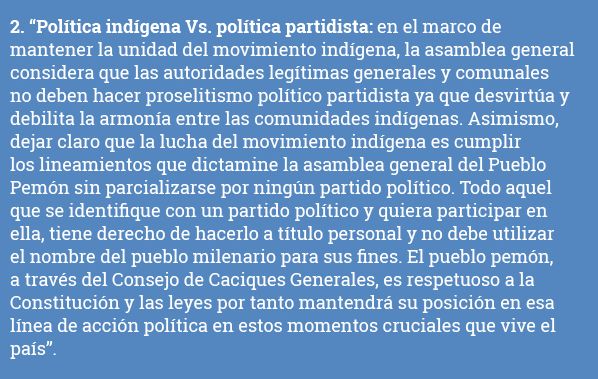

Although the Caciques of the Council are fully aware of gold mining inside Canaima, none of their statements issued in the past year have been aimed at condemning or putting an end to it. For example, an open letter written by the captains on October 4, 2018 questions environmental activists for their fierce criticism of illegal small-scale mining instead of protesting against the recent buildings erected in front of the Kanaimó Lagoon.

This letter coincided with the arrival of government officials to Canaima National Park. Led by Aloha Nuñez, Minister of Indigenous Peoples and Víctor Cano, Minister of Environmental Mining Development, the group was to meet with the indigenous community to discuss the risk the territory faced of losing the World Heritage Site distinction as a result of small-scale and artisanal mining.

In other matters included in the dispatch, the indigenous leaders limited themselves to claim their role in the management of tourism in Canaima as well as demand the implementation of trades which would allow them to receive earnings alternative to mining.

Juvencio Gómez, former captain general of Sector 6 in Pemón territory (Western Sector of Canaima, Gran Sabana) confirms that in the past few years, the Council has openly supported mining operations.

“They have all visited communities and campaigned about the benefits of the Mining Arc and the special block in Ikabarú (Sector 4 of Pemón Territory)… that’s what they are up to. The caciques have a quota for fuel and machinery as well as full authorization to transport machinery in the mines (…). They negotiate constantly. It’s not going to make them rich, but in times of need everything goes”, he says. Mr. Gómez admits that gold is mined not only in Kamarata (Carrao River) but also in the banks of the Kukenán River and the Roraima tepui, both in Gran Sabana, as well as in Santa Elena and Wonken. He claims that military officers makes round in all of these places, transporting the equipment the Pemón peoples need for gold extraction.

A “loophole”

The Council of General Caciques of the Pemón Peoples was set up in March 2013 as a need to create a governing body which would look after the interests of this ethnic group without any kind of political limitation.

“It was created as a reaction to the partisan cooptation the Federation (Indigenous Federation of the State of Bolívar, FIEB) had since 2008. In 2010, the idea for the creation of this council began to take force in view of the abandonment of local efforts by the Federation and its complicity in government projects in Southern Orinoco which hurt indigenous communities”, says Vladimir Aguilar, an attorney specialized in indigenous rights and coordinator of the Indigenous Affairs Work Group (GTAI for its acronym in Spanish) at Los Andes University.

A similar idea is contributed by Carlos Somera. “When problems arise in the Pemón world such as mining, lack of public safety and clashes with the Armed Forces on mining topics, the FIEB and CONIVE (National Indian Council of Venezuela), who are supposed to be national and regional organizations, never take a stand in favor of the Pemón people because they already have a pact with the United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV for its acronym in Spanish). They are always partial to the party or the government”, says the representative of the Council’s Institutional Alliance Commission.

As a member of the Council, Mr. Somera points out the “loophole” created when the Federation did not take a stand on gold mining or the armed attacks occurred in Las Claritas and La Paragua (both of them indigenous mining territory) which affected the entire tribe.

This statement coincides with several sources in Canaima who claim that the birth and promotion of the Council of Caciques is broadly related to gold mining in Pemón territory. For this reason, says an anonymous source, the majority of its members are in favor of mining. “The Council of General Caciques was born in 2013 with the purpose of organizing the mining activity. They want to know nothing about conservation”, says another source.

Juvencio Gómez says that the main detonator behind the creation of this organization was the arrest of 40 officers of the Venezuelan army in February 2013 by the Pemón people in Urimán as a means of protest against constant abuses.

An article published in the Correo del Caroní reveals that this protest was caused by the lack of flights in the region as well as food shortages. In that same article, Nelson Ramírez, who was then the Cacique of the Urimán sector and is currently the Head Cacique, pointed out that the measures to combat mining implemented for the Guayana Strategic Integral Defense Region (REDI for its acronym in Spanish) affected the Pemón peoples as many recognized that mining “is their only source of income”, said the article.

The Caciques’ involvement in mining operations continues to these days. “Many of these captains request commissions from the miners”, claims a Kanaimó resident who wished to remain anonymous.

Before the Council of Caciques took the reins on territorial and mining operations from the Pemón people, the institution that concentrated the power of the region’s aboriginals was the Indigenous Federation of the State of Bolívar (FIEB). Created in 1972, it was composed by captains who represented each of the communities composed by at least 15 ethnic groups who live in the state. They are the Pemón. Kariña, Akawaio, Arahuaco, Mapoyo, Piaroa, Eñepá, Sanema, Warao and Jiwi, among other groups.

Through the years, the Federation has stated its endorsement to Hugo Chávez’s political ideology. Most notable examples are the statements given by its leaders.

“The Indigenous Federation has always supported the revolutionary process which is why we are a part of the patriotic alliance led by the National Indian Council of Venezuela (CONIVE) and have been a part of the Revolution’s 18 electoral triumphs. This forthcoming December 6 (election) will not be the exception”. These were the words pronounced by Álvaro Fernández, FIEB president at a rally organized by the United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV) prior to the Venezuelan parliamentary elections in 2015. Today Mr. Fernández is a representative for the State of Bolívar in the National Constituent Assembly which was installed in 2017 to serve Nicolás Maduro’s government interests without any opposition.

Álvaro Fernández at a rally in support of Bolívar Governor, Justo Noguera. Source: www.e-bolivar.gob.ve

Álvaro Fernández at a rally in support of Bolívar Governor, Justo Noguera. Source: www.e-bolivar.gob.ve

The election mechanisms in both indigenous organizations are entirely different. While the leaders of the Federation are voted upon by direct vote, the Council abides by the “Cacicazgo” where communities elect their communal captains and these in turn decide who shall be the General Cacique of the sector. These in turn are in charge of electing the Secretary General of the Council. Jean Carlos Velásquez is the current Secretary General and Néstor Ramírez the Head Cacique.

Although the Council’s initial idea was to separate itself from the chavismo ideology and take a neutral position that would benefit the Pemón people, existing statements that allow for doubt. In a statement posted on their official Facebook page on July 4, 2019 the organization let it be known that fuel dispatch had been reestablished to normal levels in remote communities. It also informed about an increase in gasoline quota for the aviation industry which was approved of in a meeting attended by the Governor of Bolívar, Justo Noguera, and Brigadier General Jilmer Ochoa, the supreme authority on control and distribution of fuel. Also, in its closing paragraph, widely criticized by online users, the Caciques took a stand on Venezuela’s complex humanitarian emergency: