With close ties to the Chávez and Maduro Administration, this Venezuelan businessman has reappeared in the scene to supply Venezuela with gasoline. One of PDVSA’S trump cards, he has juggled his way through US sanctions by adding 46 additional vessels, most of them chartered, to prevent the oil company’s own fleet from sinking

Wilmer Wilmer Ruperti does not need a life boat to come to the rescue. When he went out to help Hugo Chávez in the early 2000’s and most recently when he did the same for Nicolás Maduro, he used oil tankers under his control. A merchant seaman, with two post graduate studies in the United Kingdom and more than two decades of work experience in the Venezuelan oil industry, Ruperti became a magnate largely because of his transport businesses with Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA). At one point he was compared to King Midas, turning anything that could float into gold.

The businessman was responsible for helping put an end to an oil strike against Chávez at the end of 2002 and early 2003. This oil shutdown had paralyzed PDVSA’s oil tankers which were pivotal for the export and domestic transportation of fuel. In 2020, Ruperti made himself available again when he admitted to a news agency that he had dispatched 300,000 barrels of gasoline to Venezuela. It was, he assured, a humanitarian gesture. Severe shortages of fuel generated by the paralysis of the State-run oil corporation, the collapse of public finances and US sanctions had prevented the Maduro Administration from either importing or self-supplying the country with gasoline. Despite being under American watch, Ruperti claimed that he had notified US authorities about the operation and promised another million barrels.

The businessman’s reappearance in the public scene, this time in the role of savior who has only been able to fulfil a part of the plan, is merely an example of the tricks PDVSA has had to play in the middle of a disastrous situation for the oil company’s fleet of tankers and minor and auxiliary vessels. This is the basis of the following report published by Alianza Rebelde Investiga (ARI) together with the Latin American online platform for journalists CONNECTAS.

Internal documents obtained for this report confirm that seven freighters owned by PDVSA and its subsidiaries are docked in Venezuelan ports as well as abroad as they await repairs or the issuance of international certifications that will confirm their insurance. This represents almost a third of the oil company’s fleet of tankers. An eighth oil tanker was added to the group on November 5, 2020 after catching fire in Cuba. This crippling situation has led the company to spend more than $75 million in payments for chartered vessels, according to calculations between 2017 and August 2020 made for this report.

The operation of PDVSA’s ships has fared no different. In mid-2019, when General Manuel Quevedo was still behind the presidency of the corporation, the management of eight freighters belonging to PDVSA was handed over to a Venezuelan company which had been founded barely a few months before. Once appointed, this company hurriedly scoured for a crew to operate the vessels. All of this happened right after a German company abandoned its administration on account of pending debts. An even worse situation was set forth by a Chinese State-run company who recently seized three of PDVSA’s super tankers. These ships were assets of a company they both had shares in, according to news agencies.

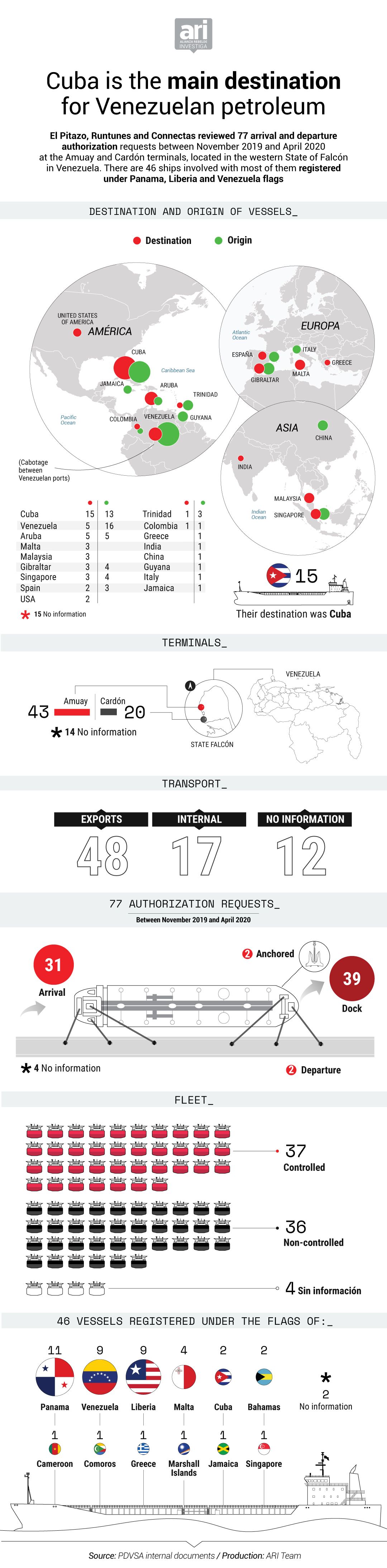

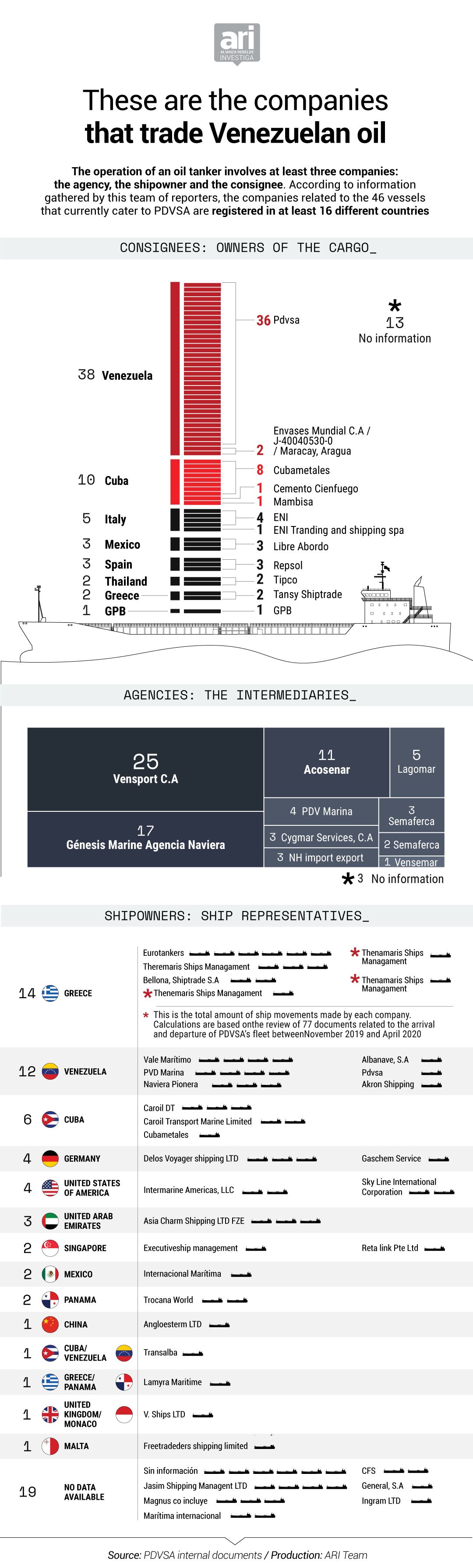

This investigation had access to information on a series of ship arrivals and departure time schedules. This list confirms that 46 tankers, nearly all of them charters, have been operating with crude oil and its derivatives. Five of them remained active despite being on the list of US sanctions that included 63 ships in 2019.

These documents correspond to a period of time between August 2019 and March 2020. They reveal that after cabotage operations within Venezuela, the most frequent routes included transporting cargo to Cuba, a nation whose government has been a strategic ally to Hugo Chávez since the days of Fidel Castro, and later on to his heir, Nicolás Maduro. More than $30 billion worth of oil were sent to the Caribbean island between 2004 and 2014. $11 billion alone were spent on electricity generation. It is worth noting that electricity is scarce in Venezuela. Despite the current crisis in production and in PDVSA’s fleet, Caracas never abandons Havana.

Ruperti was the key figure who helped end the 2002-2003 oil strike against Chávez

The majority of the oil tanker movements referred previously have been made by vessels belonging to Greek shipowners, a global power in the business of maritime cargo. The movements are managed through the intermediation of Venezuelan agencies, many of them with a history of work relations with PDVSA, according to examined documents. Aside from the ships registered in Venezuela, the majority of the tankers possess flags from Panama and Liberia, two countries that offer greater facilities for the legal operation of shipping companies as both allow open registries.

Furthermore, sources and documents consulted for this investigation have confirmed operations have changed in light of the new environment created by foreign sanctions. Common practices include: ship-to-ship fuel transfer; charter payments in cash or through complex financial schemes; doing business with new allies who are willing to risk controls; and the restriction of providing basic information to oil tanker captains such as charterparties. Additional measures have included the deactivation of automatic identification systems (AIS) to avoid tankers from being tracked on certain routes. Examples of this behavior have been attributed to the ships chartered by Ruperti to cargo fuel to Venezuela as well as others to which PDVSA has appealed to.

All of these actions have been carried out in an environment where operations related to large carriers has also been clouded by disorder and irregular actions, according to revised internal audit reports. These documents, which contain accounting evaluations carried out in 2017, confirm that the inoperability virus has also reached the fleet of auxiliary vessels and tugboats belonging to PDV Marina. The documents also reveal that this company as well as PDV Naval, the subsidiary entrusted with the development of infrastructure and technical assistance in the purchase of tankers, incurred in unsupported disbursements and out-of-protocol recruitments. They also prove that the purchasing systems of the Dianca shipyard, responsible for the maintenance of larger and smaller vessels, are vulnerable to corruption and that additional expenditures to the original budget plans were astronomical.

Repeated requests for information regarding these points were submitted and ignored by the current President of PDVSA, Asdrúbal Chávez. A former Minister of Oil, Chávez also occupied key positions in the corporation between 2004 and 2014 for the design and management of a fleet which today seems dismantled. As President of PDV Marina and PDV Naval, he was responsible for the acquisition and management of vessels. He was also Executive Director and Vice President of Trade and Supply, an area that governed third-party charters.

In an interview for this report, Rafael Ramírez, a former president of PDVSA and also former Minister of Oil, distanced himself from any responsibilities in regards to the current state of the fleet. He also defended former collaborators such as Eulogio del Pino and the late Nelson Martinez, who succeeded him in the presidency of PDVSA and ended up being jailed by a judicial system with close ties to Nicolás Maduro.

Ramírez claimed that at the time he left the corporation in 2014, after more than a decade presiding it, PDVSA managed 83 ships. This number includes all of the self-owned vessels as well as those chartered to third parties or companies in which the oil corporation shared property with public naval conglomerates from allied countries. Therefore, Ramírez affirmed that all questions should be addresed to others. “At the moment, no oil can be carried out of PDVSA because they destroyed the fleet. I wish we still had those ships. This is an excellent question for Asdrúbal Chávez or General Manuel Quevedo”.

Adventures on the Seven Seas_

Ruperti is an old acquaintance in the choppy waters in which PDVSA sails. During the 1990’s he stopped working for the oil corporation and became the representative of several Russian shipping companies. In an interview at a television station he owns, Ruperti stated that before Hugo Chávez’s arrival at Miraflores Palace he had already managed to run a fleet that handled 125,000 barrels of oil a day from the Venezuelan oil company. His career, however, gave an enormous jump after the 2002 oil shutdown crisis. His participation led Hugo Chávez to award him the Order of the Liberator, one of the highest distinctions awarded by the Venezuelan State.

The fortune Ruperti amassed with businesses inside the country and abroad not only allowed him to purchase a television station but also to extend political gestures which would be out of league for ordinary pockets. At one point he gifted Chávez with two gold-encrusted pistols that once belonged to Simón Bolívar for which he paid more than $1.5 million at a Christie’s auction. He also paid the legal fees for the defense of the nephews of Cilia Flores, Nicolás Maduro’s wife, who were ultimately sentenced to 18 years in a New York prison for drug trafficking.

In 2020 he has repeated something that he used to say during the 2002-2003 oil shutdown crisis: his oil operations are solely designed to help the Venezuelan people. However, this man is no hero. Accusations of extorsion, bribery and fraud, especially in obtaining PDVSA deals, have repeatedly pointed fingers at him. Although he has denied these claims on his television station, Ruperti did not answer to repeated interview requests for this report.

Ruperti is just one of the trump cards that PDVSA has used to keep afloat. Of the 46 vessels identified in the filtered documents which this investigation had access to, only three are owned by the oil company. The list was drafted for this report on the basis of 77 ship departure/arrival authorizations given during a period of five months at the Venezuelan port of Las Piedras, located in the Paraguaná Peninsula, Falcón, close to the Amuay Refinery. The list includes information on the ship’s name, identification number, destination or origin and the product it carries. It also mentions the list of companies involved: consignees (owners of the shipment), shipowners, and agencies (port authorities).

The movements reflect the company’s priorities. With 15 departures, Cuba was the main destination for exports and PDVSA and Cubametales the most frequent consignees. The information reveals that despite being included in the list of US sanctions, several tankers registered movements in the first trimester of 2020. Among them are the Paramaconi (PDVSA); The Sandino and the Petión (owned by Transalba which is a joint venture between PDV Marina and Cuba’s Internacional Marítima); the Carlota C and the Esperanza (Caroil Transport Marine). This has made room for operations that either end up in the exchange of oil for goods or in third-party debt payments. According to public data bases, Caroil Transport Marine is managed by Guillermo Rodríguez Lopez-Callejas, a Cuban citizen, who also serves as president of Transalba’s two subsidiaries in charge of managing the Sandino and the Petión. Carlos Sánchez Berzaín, Director of the American Institute for Democracy, a non-profit organization based in Florida, is of the opinion that “Sanction measures should be fully applied to Cuba for having intervened Venezuela and helped uphold Maduro’s usurpation”. Maduro’s government considers US sanctions as a violation of Venezuela’s sovereignty.

The inventory that this report had access to mentioned Eurotankers and Thenemaris Ships Management, two Greek shipping companies. The movements of three Venezuelan agencies were also noteworthy: Venezolana de Servicios Portuarios, C.A. (Vensport); Genesis Marine Agencia Naviera 17 and the Asociación Cooperativa de Servicios Portuarios (Acosenar) with 53 movements.

Vensport and Genesis Marine are two companies that have gone beyond Venezuelan borders. Created in Zulia in 1974, Vensport was also registered in Florida in 2018 and in Panama in 2019, according to the commercial registers in both countries. The company is directed by five people in Panama and by three in the United States. In both cases, Juan Ramón Ysea Ortega and Ubaldo Alí Colmenares Ortega are at the head.

In turn, Genesis Marine created a parent company in Panama (Genesis Group SLP, Inc.) and a subsidiary in Guyana in 2018. The company’s LinkedIn profile states the following: “Aiming to consolidate the Group’s position as a leading regional actor, in 2016 we renamed ourselves Genesis Group SLP, Inc. to provide solutions in shipping, logistics and products (SLP) across the Americas”. Lewis Ibarra and Migdalia Mota appear as owners of Genesis Marine. They are also owners of two other companies registered in Panama: Genesis Ship Services created in 2010 and Genesis Logistic & International Projects S.A. in 2014. At the end of September and early November 2020, the team of reporters of this investigation tried unsuccessfully to contact representatives from Vensport, Genesis Marine and Acosenar.

PDVSA’s search for new players and alternate channels has become intense. Besides Wilmer Ruperti, the oil corporation has relied on Iranian tankers that have been willing to transport fuel to Venezuela. Shipping companies linked to Alex Saab have been used as well. Saab is currently under arrest in Cape Verde, accused of serving as a front man to Nicolás Maduro. In its study on the impact of US sanctions in Venezuela, C4ADS, a Washington-based think tank focused on global security issues, identified 103 vessels that visited Venezuela for the first time in 2019. All of these tankers appear to be owned by just 41 companies, according to the report. Three Greece-based companies possess the largest fleets: TMS Tankers Limited, Delta Tankers Limited and Eastern Mediterranean Maritime Limited.

A stranded fleet_

As business with third parties flourishes, PDVSA’s own ships are embattled in a crisis that goes from inoperability to legal conflicts with former allies. The list of stranded tankers obtained by this report included the Negra Matea and the Tamanaco (both Aframax models), the Proteo and four of the seven Greek Gods (all of them Lakemax models).

The Negra Matea has suffered the worst. Since May 25, 2017, the oil tanker has been docked at the Lisnave shipyard in Setubal, Portugal. To date, it is awaiting the “solution of financial problems that will allow dry-dock operations”, according to an internal document from PDV Marina dated May 8, 2020, which this investigation had access to. Aside from the substantial debt the Portuguese shipyard is owed, in three years this tanker’s inoperability has caused PDVSA to lose approximately more than $29.8 million in cost opportunity.

With barely eight years of construction, the Tamanaco has been anchored at Punta Cardón, Falcón since 2018. Machinery damage has caused this tanker to remain inoperative, according to the report obtained. Its crew awaits instructions for its repair and the losses in cost opportunity are greater than $18.3 million.

The Proteo caught fire on August 19, 2019 and since then it has remained docked as the insurance company has yet to receive the final paperwork in order to approve the damage repair. A year later, its inoperability losses are around $9.4 million. The other ships that are stranded are part of the list of Greek Gods. An additional $18.2 million are caused by the same class models which are anchored in Falcón as they wait for maintenance: the Zeus, the Eos, the Hero and the Nereo.

A source in the industry claimed that these vessels also have navigation restrictions because their classification certificates expired. These are documents that are issued by classification societies that vouch for the technical and operational standards of a ship. According to news agencies, the Teseo, which was active, caught fire on November 5, 2020 at Holguín, Cuba as it was discharging oil.

“Sanction measures should be fully applied to Cuba for having intervened Venezuela and helped uphold Maduro’s usurpation”

Carlos Sánchez Berzaín

Some are privileged enough to have their “Greek Gods”_

In addition to those already mentioned, the Greek Gods also include the Parnaso and the Ícaro. By the end of 2019, the entire operation of the Greek Gods was handed over to a recently created company: Blue Oceanic Services. Founded in May 2018, the company is registered in Punto Fijo, Estado Falcón. According to its commercial register, it is owned by six Venezuelan citizens. Among them, is a man who has been identified by the workers as Oswaldo Marval.

Shortly after its creation, the company began to be questioned by its crew of seamen for not honoring their work commitments. A company with a similar name was registered in 2020 by Nhur Canelón in Florida, U.S.A. Among their clients, according to their web page, is the German company Bernhard Schulte Shipmanagement (BSM) who used to operate the Greek Gods. Canelón is also among the stockholders of Blue Oceanic Services in Venezuela.

BSM left Venezuela in March 2019, shortly after the United States government began issuing sanctions, alleging late payments. According to Reuters, that same month, the company moved to collect these payments by legally detaining three oil tankers: the Parnaso, the Río Arauca and the Arita, which is managed by another of PDVSA’s subsidiaries: Albanave.

The story of the Parnaso is filled with flukes. The oil tanker was located at the Lisnave shipyard in Setubal. In September 2019, a Portuguese court put it up for sale so that the maintenance company could collect its payment. Someone bought the vessel, secured an agreement with PDVSA and returned it to them.

There were more legal conflicts with former partners who claimed their debts. This was the case of PetroChina International and Russia’s Sovcomflot. Alliances with both of them were made through letters of credit with PDVSA for the purchase of new vessels and the chartering of others at more competitive prices.

Together with PetroChina International, PDVSA created CV Shipping, registered in Singapore. Four Very Large Crude Carriers were bought and operated by this company: the Carabobo, the Boyacá, the Ayacucho and the Junín.

However, US sanctions stripped these ships from their insurance and in August 2020, CV Shipping filed for bankruptcy. Using court documents, Reuters reported that PetroChina International seized three of the super tankers. In the case of Sovcomflot, an alliance was set up in 2010 that allowed the Russian company to charter tankers to PDVSA. A 2015 inventory reveals the existence of 11 vessels. Two years later, the Russian shipping conglomerate held onto $20 million worth of Venezuelan oil aboard one of its tankers in hopes of collecting a debt it claimed to be owed by the Venezuelan corporation. A UK Admiralty Court was left to decide if Sovcomflot could take the oil. The fact that allies are severing decade-long ties, especially during PDVSA’s weakest moment, is a signal of the abundance of irregularities in relation to the services provided by its fleet.

For example, internal PDV Marina audits revealed that between 2015 and 2016, just as debts with its former allies were growing, the company disbursed more than $105 million in small vessel chartering without the necessary documentation required for this type of procedures. Actions like these severely damaged the “transparency” and the “traceability” of these transactions. During this time, 34% of the company’s tugboats and 64% of its motor boats were inoperative. At other subsidiaries such as PDV Naval, at least $18 million were used for recruitment processes that did not comply with internal regulations, namely because the management office proceeded without authorization from higher authorities or skipped the committees that regulate third-party agreements.

Internal audit reports in PDVSA also revealed a negative balance for Dianca, a shipyard company that was owned by the Venezuelan Ministry of Defense until 2009 when PDVSA acquired 60% of its shares and for PDVSA Naval, a subsidiary created in 2008 for the design, acquisition, construction, repair and maintenance of PDVSA’s ships. Samples of the report say the following: “A 348% deviation of the budget in Bolivars. Weaknesses in budget creation and control. Inconsistencies in the budget for purchase orders… In 75% of contracts executed by PDVSA Naval, the Manager of PDVSA Naval did not have approved financial delegation to incur in recruitments… 1,924 invoices authorized between 2015 and 2017 for an amount of Bs. 841 million, just in the Puerto Ayacucho-Bolivar axis alone… PDV Marina is using an Excel document for small vessel chartering purposes”. When adding these and other items and adjusting the Bolivar to the 2017 US $ exchange rate, the loss amounts to $370 million.

More impressive is the expenditure of money not contemplated in the budget for operations in the water and which amount to a whopping $1.8 billion. This figure is distributed among Suezmax and Lakemax class tankers as well as boats and tugs. “The largest deviation (occurred) by the Inciarte tanker which had to be disincorporated and the Guanacoco which was docked in 2015”.

All of these are currents of a tide that left PDVSA relying on any help it can get.

A secret naval battle_

A case involving Wilmer Ruperti serves as an example of the nature that PDVSA’s naval operations have acquired. Evangelos Marinakis, a controversial Greek mogul who owns the Olympiacos Football Club and several shipping companies accused Ruperti of plotting an operation to avoid US sanctions, according to an Associated Press report published in July 2020.

In March 2020, Marinakis chartered the Alkimos oil tanker from Ruperti to carry 100,000 barrels of gasoline to Aruba. The instructions were that the cargo would be transferred at sea to another ship. However, the Greek businessman assures that he was denied access to information on details of the transaction. Furthermore, he claims that the transfer was done in an area not approved by island authorities, using another ship that had been continually visiting Venezuelan ports. Suspicious of the operation, Marinakis ordered that the tanker be deviated to the Gulf of Texas. Ruperti responded by accusing Marinakis of stealing the cargo, which was auctioned off by US federal marshals.

Fuel transfer tactics such as these have become common in an era dominated by US sanctions. Other maneuvers have included changing the names of ships. Such was the case of the Nelas, a tanker that was re-christened as the Esperanza after it was sanctioned by US authorities. Deactivating satellite trackers has also been frequent. A case study included in the 2020 report published by the non-profit C4ADS regarding shipping networks in the case of US sanctions against Venezuela tracked a group of tankers owned by Eastern Mediterranean Maritime Ltd (EastMed). According to them, “of the 20 tanker vessels owned by EastMed that operated in Venezuelan waters, 18 of them showed periods of lost AIS transmission as they crossed the Atlantic Ocean”.

Ship-to-ship transfers have also become a useful tool. It is an operation that involves technical risks, but it is legal. It has been intensified because it can help manipulate data on the origin and destination of cargoes, especially if done ashore.

An internal PDVSA report detailing ship movements during the first trimester of 2020 shows that on March 11, 21 and 31, an oil tanker belonging to the State-run corporation received cargo in ship-to-ship operations. This was the Arita, a vessel manufactured in Iran and delivered to Venezuela in 2019. 360,000 barrels of oil coming from China were unloaded onto this ship by the Eurovoyager and the Eurodignity. Two months before, El Pitazo had released a video of the Liberian-flagged Eurosea and the Power M. Both of them were seen anchored close to the Amuay Refinery, transferring the cargo.

The secretive nature of these operations extends to other areas. A public officer consulted for this report even said that access to data and basic documentation such as charterships has been restricted in some cases. “I’ve particularly requested (this information) and have gotten no answer”, he said, requesting anonymity for fear of retaliation.

Article 20 of the Venezuelan Law on Maritime Commerce establishes that the captain must have a copy of the charterparty, among other documents. The provisions of this law apply to all domestic and foreign vessels in jurisdictional waters of Venezuela as well as national citizens who are at high sea or waters controlled jurisdictionally by another country.

Avoiding US sanctions has also implied the use of complex commercial and financial strategies. The affair that pits Ruperti against Marinakis reveals a network of companies and bank accounts that were employed to ensure the cargo of 100,000 barrels of oil to Venezuela. Ruperti has maneuvered his way like a fish in the water in that scenario. A recent inventory accounts for 23 companies, many of them registered with names that have imitated giants of the naval or oil industry, such as PDVSA. This has led him to face expensive legal actions in the past.

His main legal action was set forth by former allies of Novoship, a subsidiary company of Sovcomflot, the giant Russian State-owned corporation that specializes in the maritime cargo of fuel. The company claimed that Ruperti owed them $150 million for transactions made in 2003 during the Venezuelan oil shutdown. The Venezuelan businessman was accused of plotting a scheme that led Novoship executives to believe that he was an official agent of PDVSA and take control of resources belonging to the Russian conglomerate. The parties reached a settlement in 2016 after a long legal battle. However, three years later Ruperti sued Novoship for breaching the settlement in the middle of a scandal in which the Russian company was accused of incurring in illegal practices to access the businessman’s bank information and pressure him into paying the debt.

The legal battle with Novoship was a hard blow for Ruperti’s power in his businesses with the Venezuelan oil corporation. Among other consequences, as reported by El Pitazo in a previous report, the legal process implied the freezing of several of his assets. By 2012, the head of his companies, Global Ship Management, had accumulated 36 ships and a defying power within the industry. A 2008 PDVSA audit report, classified as confidential, stated the influence that one of Ruperti’s companies played on PDVSA’s Chartering Management office. At the time, the report said, this company was negotiating a contract considered unfavorable to the interests of the public corporation.

The decline of his operations hit back in 2016 when he won a $136 million contract to extract coke, a solid fuel made from the oil refining process, at the José Industrial Complex in Anzoátegui. This second wind enabled Wilmer Ruperti to assist Nicolás Maduro in supplying Venezuela with fuel. All in the name of Venezuelan citizens who are asphyxiated by the scarcity of gasoline.