In public hospitals in Venezuela, patients have to provide their own supplies or pay (in money or kind) for scheduled surgeries. Sick patients and family members are conditioned to rent equipment or buy specialized supplies from handpicked private companies. No money means no operating room and very long waiting lists

An investigation by El Pitazo and CONNECTAS

Braian Lozano Salinas has more surgeries than years of life, at 20, he has had 26 surgeries. He was diagnosed with neurofibromatosis, a genetic condition that causes tumors all over the body, when he was 2 years old.

His last visit to the operating room in Hospital Oncologico Dr. Miguel Perez Carreño in Naguanagua, state of Carabobo, was an emergency. His life depended on two simultaneous surgeries to extract a tumor that was crushing his jugular vein and carotid artery (which takes blood from the heart to the brain), as well as a tumor in his eye. That was in September 2023.

Despite its seriousness, Brian’s surgery was postponed three times. While the operating room was not available for him, other patients with non-urgent surgeries were scheduled for their procedures. The difference is they had paid to be operated on.

“It works like this: you pay 80 to 100 dollars for a private appointment with the specialist and your surgery gets scheduled in the public hospital for the upcoming week. When I mentioned this to new patients that I hadn’t seen before, they replied that they were friends with a doctor who had seen them in his private practice.” That is the account of Luisana Salinas, Braian’s mother, who discovered patients being admitted for surgery without being in the waiting list or having a medical record in the hospital.

Luisana Salinas, Braian Lozano’s mother, went to a public hospital because it was impossible to schedule his son’s surgery in the private healthcare system | Photo: Ruth Lara Castillo

Luisana Salinas, Braian Lozano’s mother, went to a public hospital because it was impossible to schedule his son’s surgery in the private healthcare system | Photo: Ruth Lara Castillo

On the verge of entering the operating room, his son’s surgery was postponed. It became clear for Luisana that corruption had taken over the operating rooms of the public healthcare system. “They admitted patients at midnight, without medical records or supplies and still, they were operated on. My son has a tumor crushing the jugular and the carotid and he has been denied surgery for the third time in a row.”

Article 84 of the Constitution of the Republic, valid since 1999, sets forth that healthcare is free in Venezuela. But Braian’s experience shows that this principle doesn’t apply for patients who need to be operated on in State hospitals.

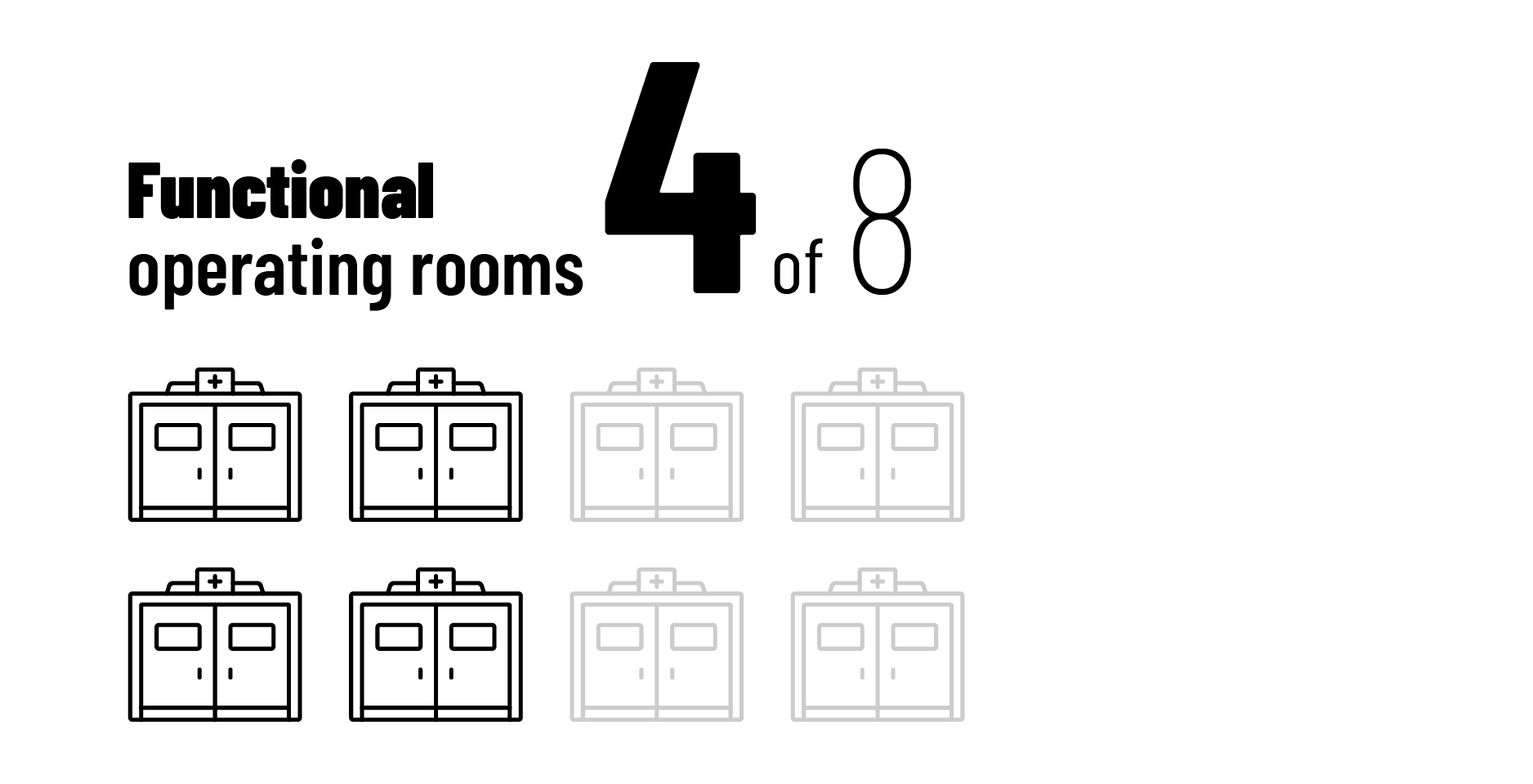

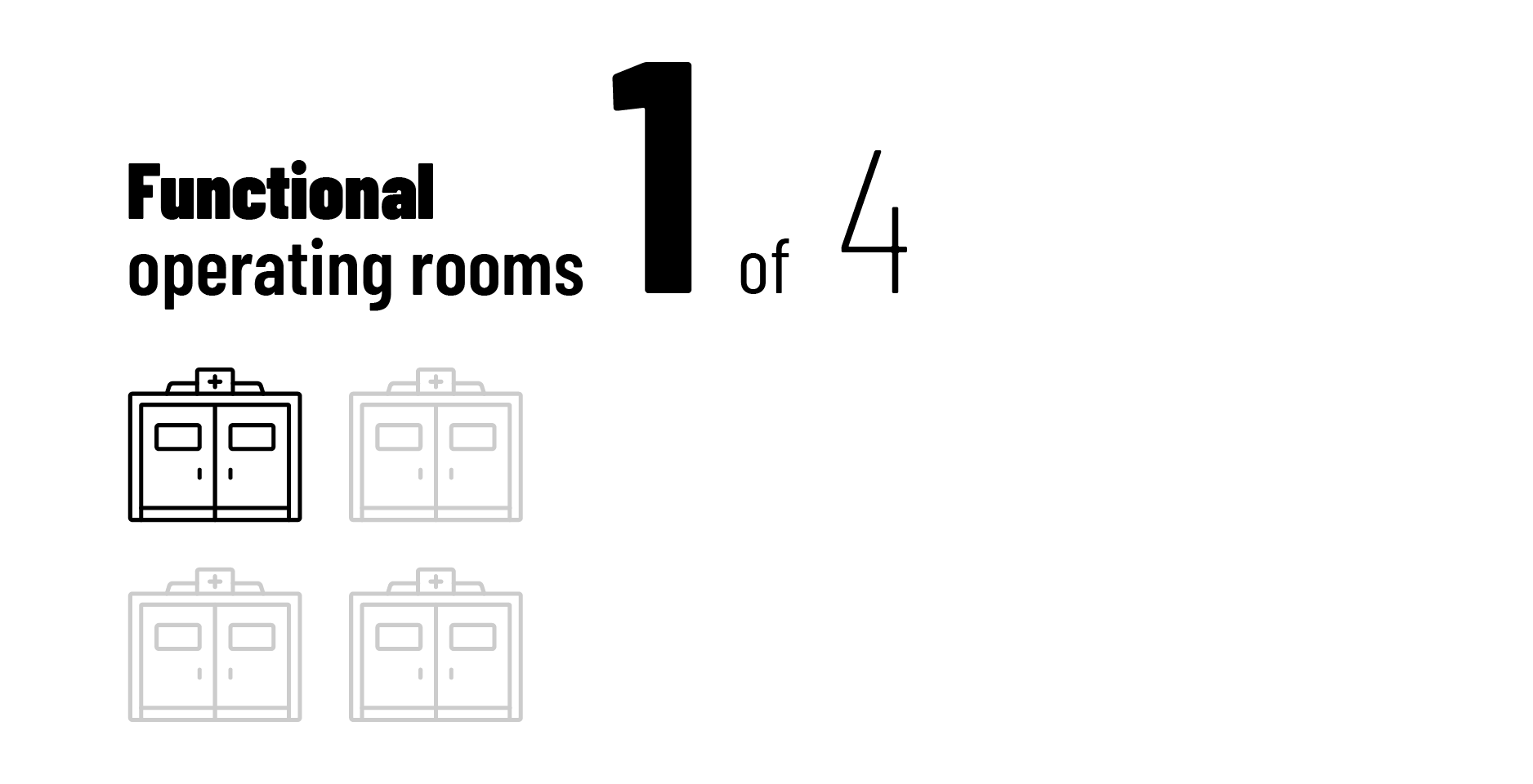

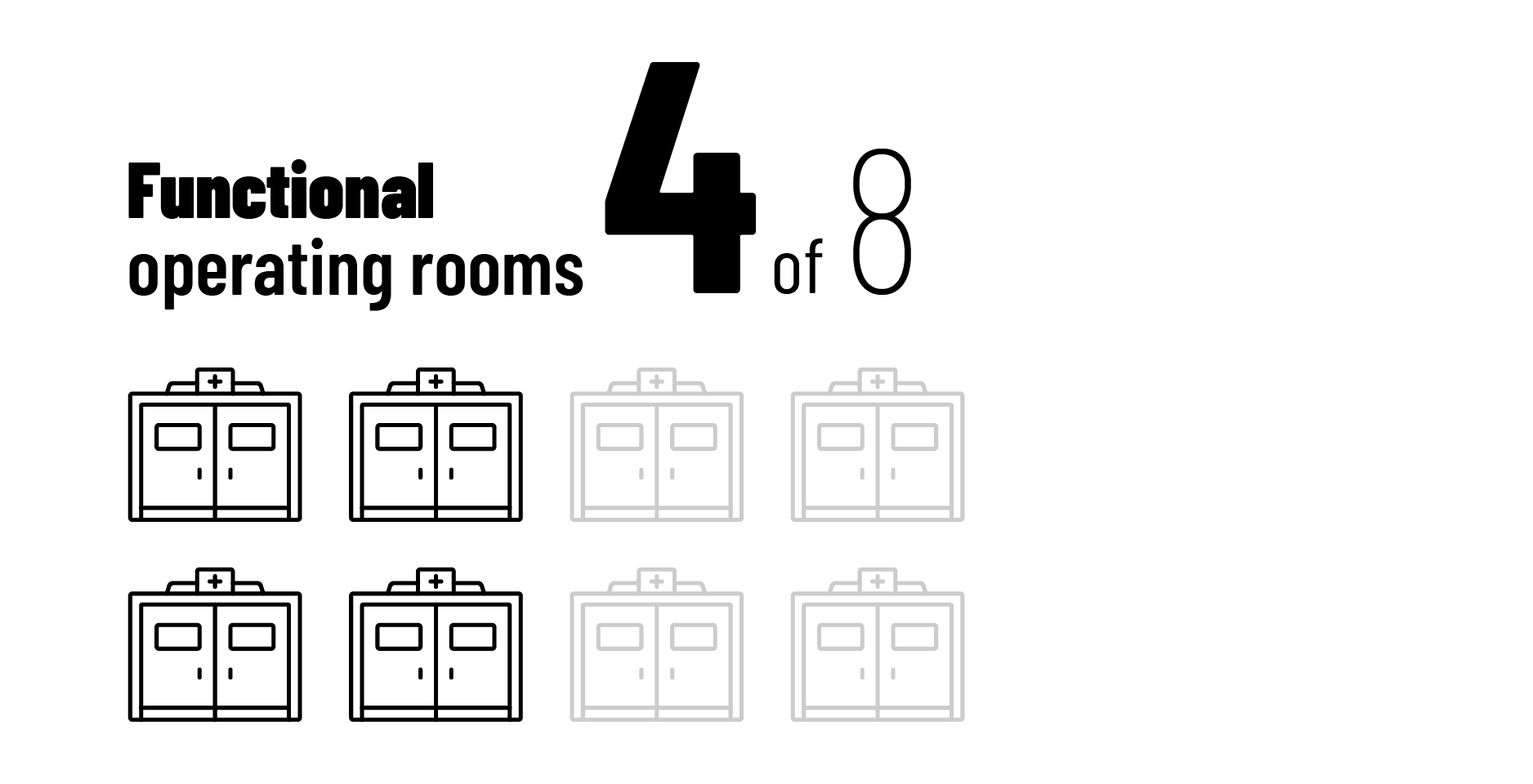

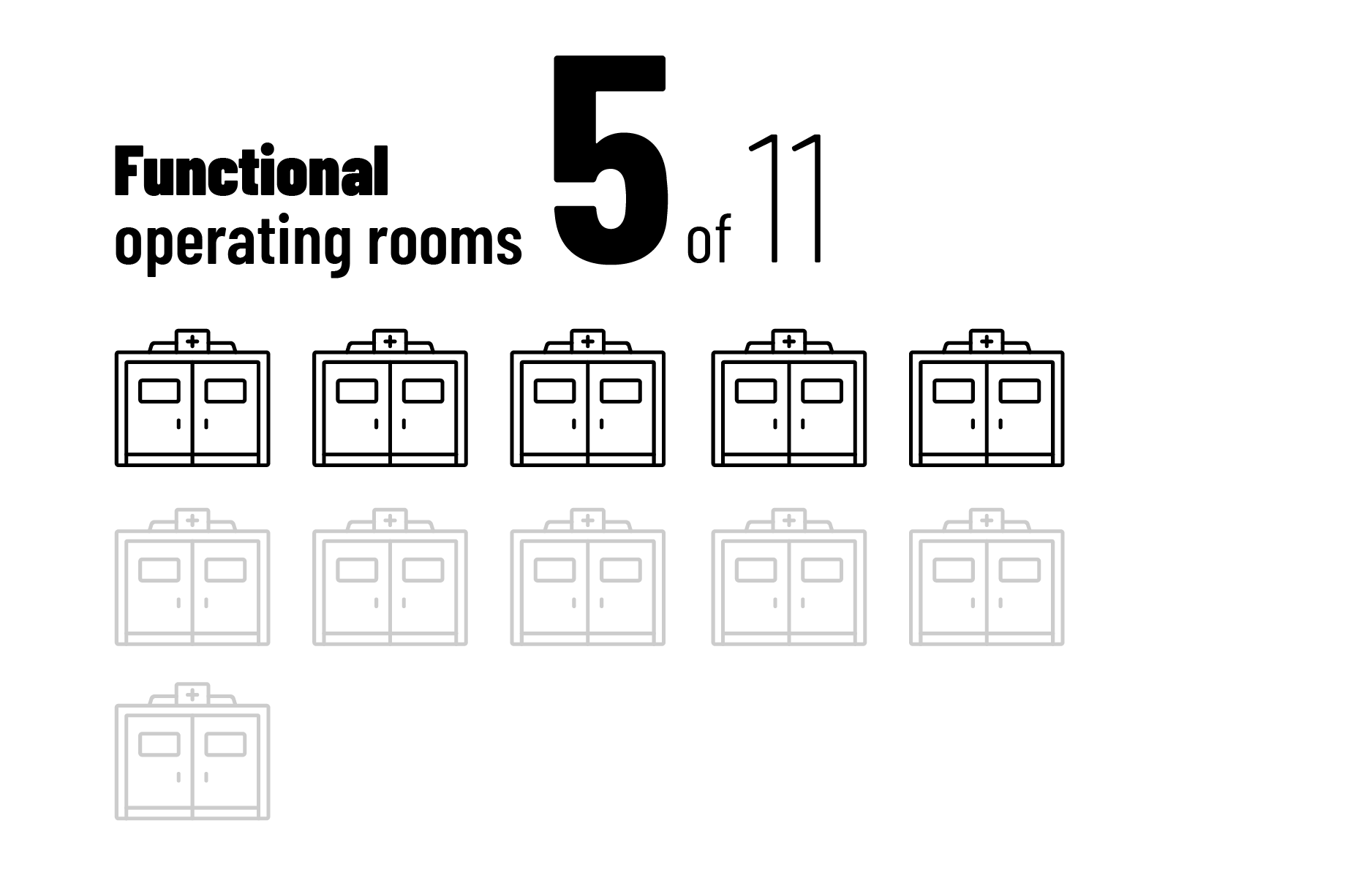

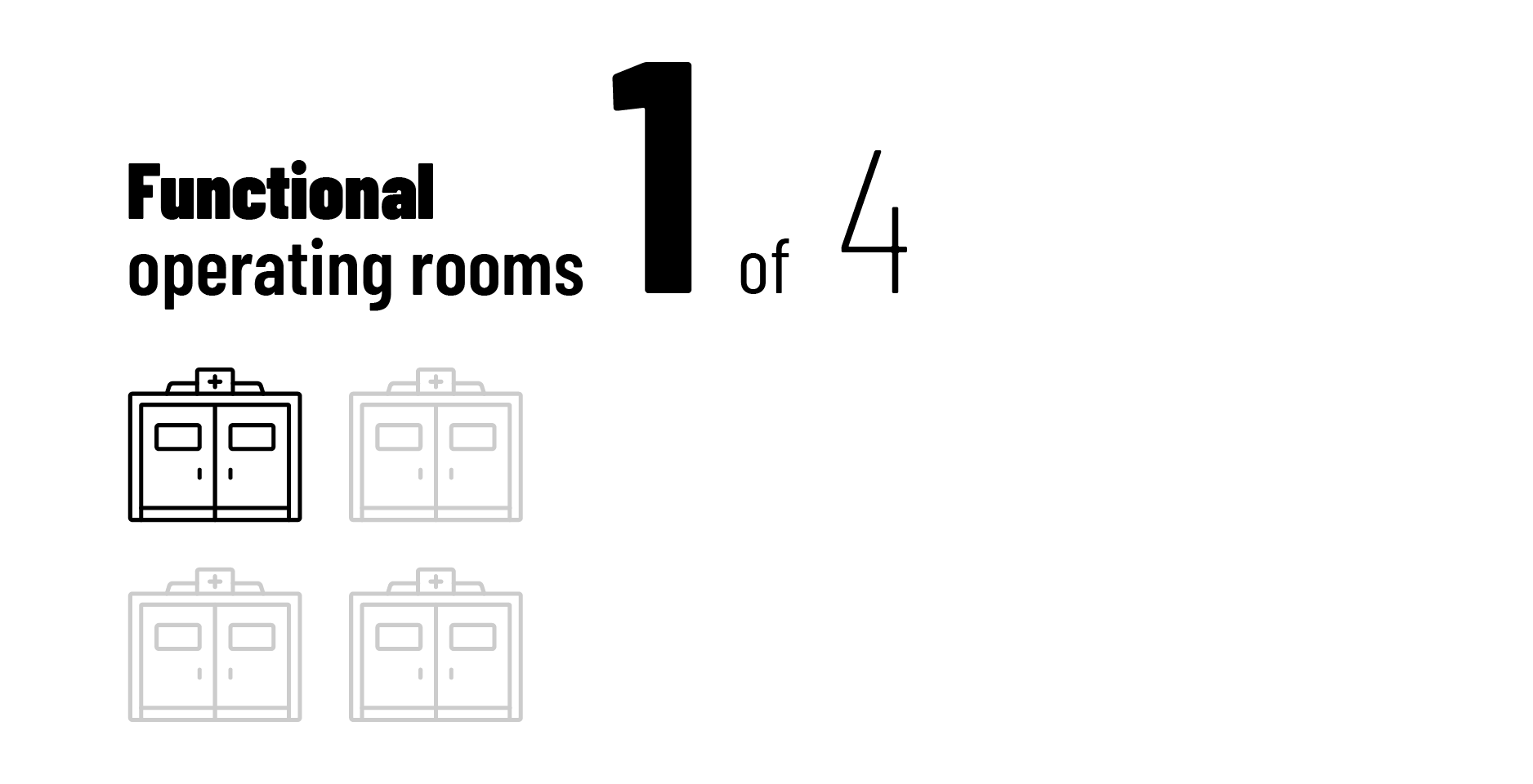

The impossibility of accessing operating rooms is repeated in hundreds of cases. Waiting times can be of three months to a year or longer in 28 to 49% of the cases of gallbladder, breast cancer, hysterectomy or prostate cancer surgeries in public hospitals. Availability of operating rooms is limited. A hospital has an average of four functioning operating rooms, although an acceptable mean would be of 10 to 15 per hospital, according to the results of the 2023 ENH (National Survey of Hospitals in Venezuela).

For a decade, the deficit in operating rooms in public hospitals in Venezuela has been dramatic. Elective (non-urgent) surgeries have waiting lists of one to 12 months, regardless of the patient's’ risk.

According to the ENH (National Survey of Hospitals), the largest health centers (classified as Type III and IV) only have four functional operating rooms – when the least acceptable number is ten.

Healthcare staff reported inappropriate charges in 31 of 45 hospitals located in 20 states and in the District Capital and which were monitored by El Pitazo for this feature. Out of 346 operating rooms available in those 45 hospitals, only 46.53% are functional.

Source: Investigation by El Pitazo. Ministry of Health, ENH (National Survey of Hospitals), Medicos por la Salud NGO, Medicos Unidos NGO, monitoring of denunciations on social media.

Hospital Universitario

Dr. Luis Razetti

Type: IV

Agency: Ministry of Health

Effectiveness: Functional

Denunciations of charges: None reported on social media.

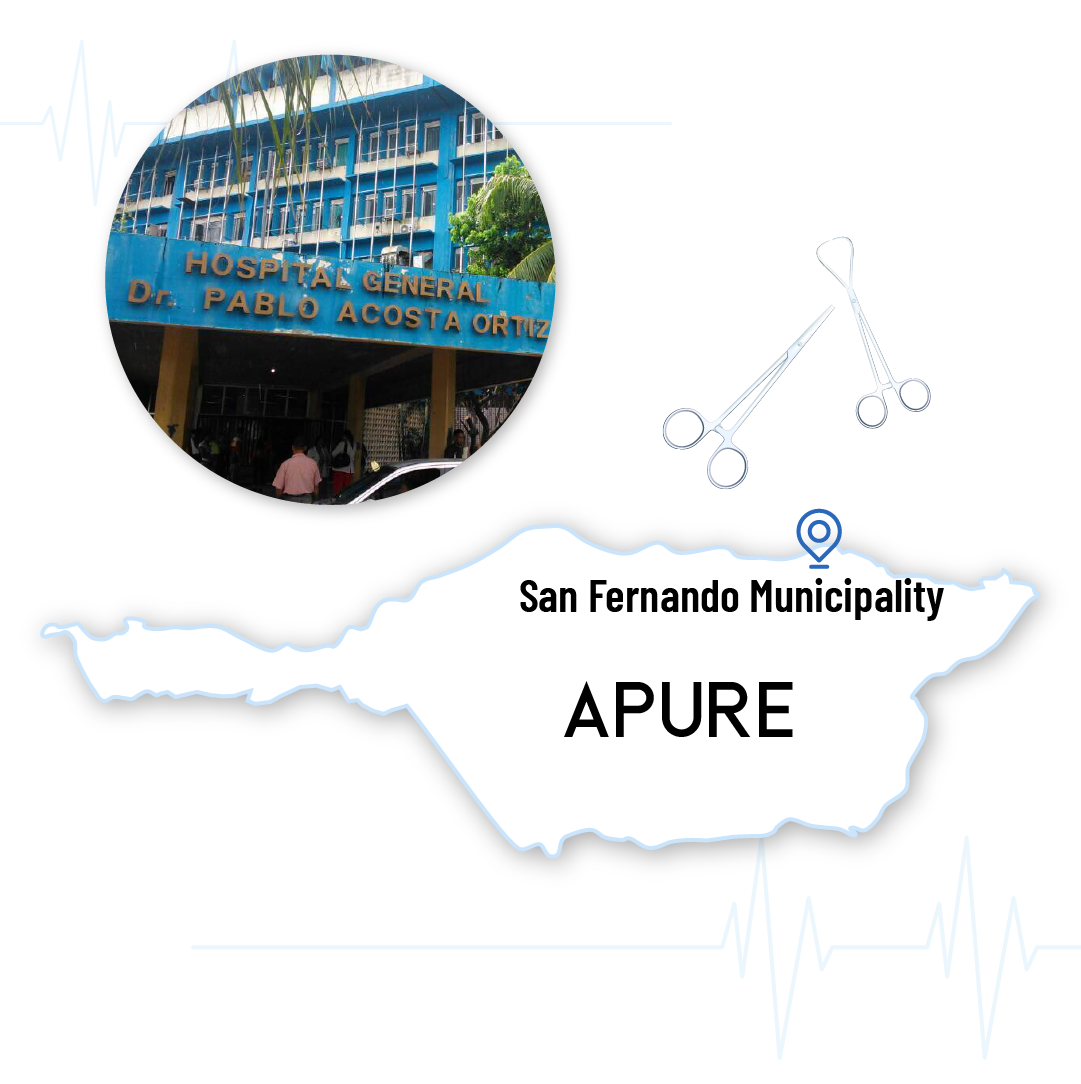

Hospital Dr. Pablo Acosta Ortiz

Type: III

Agency: Ministry of Health

Effectiveness: Functional

Denunciations of charges: None reported on social media.

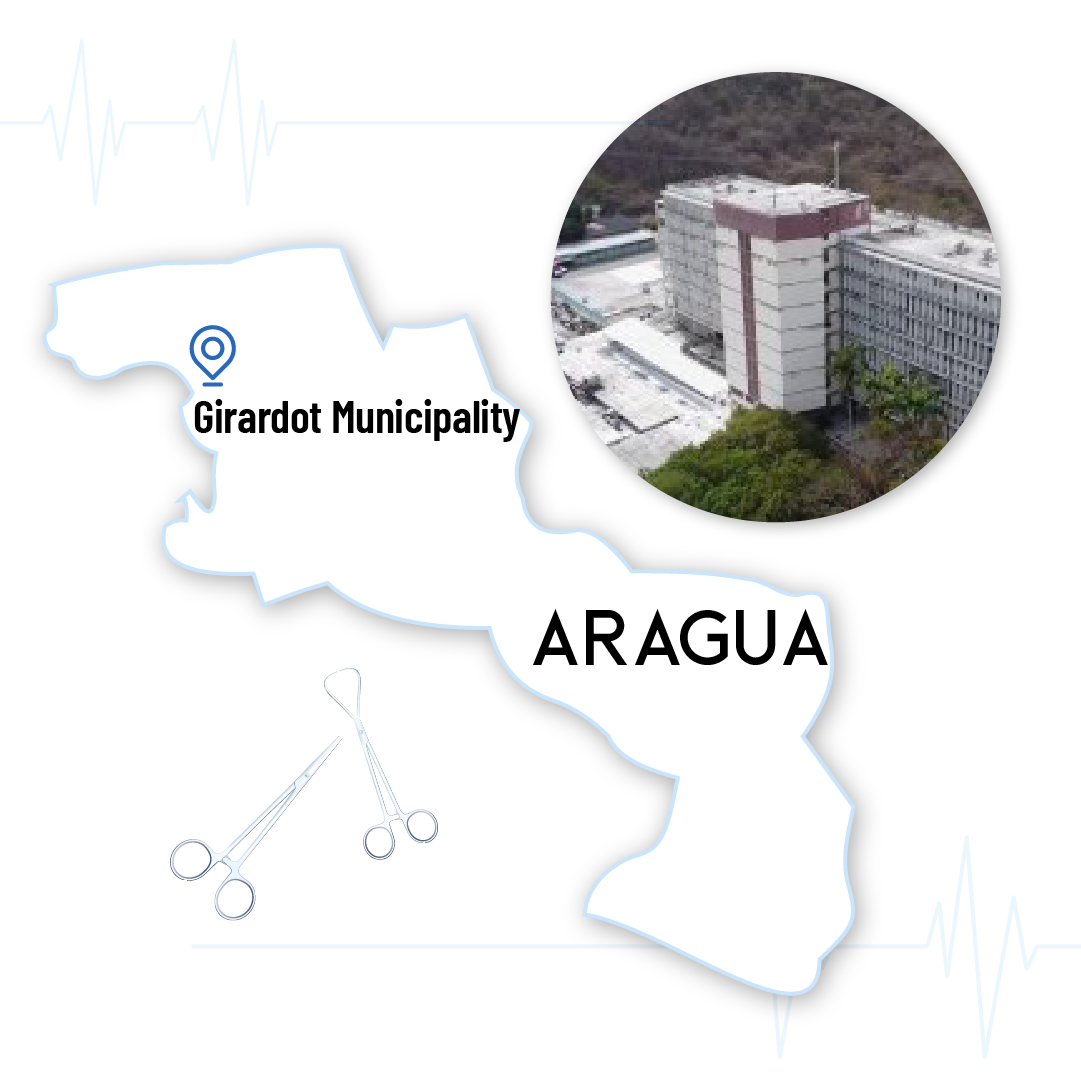

Hospital Central

de Maracay

Type: IV

Agency: Office of the Governor of the state of Aragua

Effectiveness: Functional

Denunciations of charges: In August 2021, a doctor was denounced in the CICPC for allegedly charging 3,700 dollars to a patient from his private practice for a hysterectomy undertaken in this hospital, as a user reported on X.

Hospital Militar

Coronel Elbano Paredes

Type: III

Agency: Ministry of Defense

Effectiveness: Functional

Denunciations of charges: In March 2022, a neurosurgeon was accused of allegedly transferring patients from this hospital to her private practice to request medical exams from a private medical center or else she refused to treat them.

Hospital

Dr. Luis Razetti

Type: III

Agency: Ministry of Health

Effectiveness: Functional

Denunciations of charges: None reported on social media.

For a decade, the deficit in operating rooms in public hospitals in Venezuela has been dramatic. Elective (non-urgent) surgeries have waiting lists of one to 12 months, regardless of the patient's’ risk.

According to the ENH (National Survey of Hospitals), the largest health centers (classified as Type III and IV) only have four functional operating rooms – when the least acceptable number is ten.

Healthcare staff reported inappropriate charges in 31 of 45 hospitals located in 20 states and in the District Capital and which were monitored by El Pitazo for this feature. Out of 346 operating rooms available in those 45 hospitals, only 46.53% are functional.

Source: Investigation by El Pitazo. Ministry of Health, ENH (National Survey of Hospitals), Medicos por la Salud NGO, Medicos Unidos NGO, monitoring of denunciations on social media.

Hospital Universitario

Dr. Luis Razetti

Type: IV

Agency: Ministry of Health

Effectiveness: Functional

Denunciations of charges: None reported on social media.

Hospital Dr. Pablo Acosta Ortiz

Type: III

Agency: Ministry of Health

Effectiveness: Functional

Denunciations of charges: None reported on social media.

Hospital Central

de Maracay

Type: IV

Agency: Office of the Governor of the state of Aragua

Effectiveness: Functional

Denunciations of charges: In August 2021, a doctor was denounced in the CICPC for allegedly charging 3,700 dollars to a patient from his private practice for a hysterectomy undertaken in this hospital, as a user reported on X.

Hospital Militar

Coronel Elbano Paredes

Type: III

Agency: Ministry of Defense

Effectiveness: Functional

Denunciations of charges: In March 2022, a neurosurgeon was accused of allegedly transferring patients from this hospital to her private practice to request medical exams from a private medical center or else she refused to treat them.

Hospital

Dr. Luis Razetti

Type: III

Agency: Ministry of Health

Effectiveness: Functional

Denunciations of charges: None reported on social media.

This feature by the team of El Pitazo and CONNECTAS discovered how the lack of functioning operating rooms, migration and health practitioners’ precarious salary conditions, combined with the shortage of supplies and medical material, has paved the way for a scheme of illegal charges to patients and their family members. Access to surgical services is granted only in exchange for these payments.

Braian’s mother had to wait because she didn’t pay for a private appointment to speed up her son’s surgery. Carmen, another patient interviewed for this feature, says that she was charged 300 dollars for her gallbladder surgery. A sports coach with a brain hemorrhage waited three months to be scheduled while he gathered the money for the cranial drill he had to rent to be used in his surgery in the public hospital. These and other cases compiled by El Pitazo, prove that cases of hospital corruption have become a widespread model in Venezuelan operating rooms, not just isolated cases.

“Shortage of functioning operating rooms explains why the so-called ‘waiting lists’ are so long and patients are forced to wait months for elective (non-essential) surgery, including oncology interventions,” explains infectologist Julio Castro, coordinator of the ENH, in a statement in January 2024. That same statement was ratified in the news letter issued by the ENH in January of this year.

The ENH reveals that in 90% of the monitored hospitals, the staff asks surgical patients for supplies. In the last quarter of 2023, shortage of supplies in operating rooms in these health centers reached 74%.

Last January, the ENH estimated that a patient needs at least 81 dollars for basic surgical supplies, which ought to be provided by the State. That figure is the equivalent of 22.5 minimum monthly wages in Venezuela (which amounts to 130 bolivares, or 3.60 dollars at the official exchange rate in February 2024).

The situation is dire in a country in which 87.8% of the population –more than 25 million inhabitants– depend exclusively on the public healthcare system, and 87.6% don’t have health insurance in the private system, as revealed by the Fourth Follow-Up Report to the Complex Humanitarian Emergency in Venezuela of 2023 by the platform HumVenezuela. The organization calculates that 97.6% of public healthcare system users don’t have financial protection and 54.8% lack resources to cover health expenses.

As is the case with other patients, Braian’s parents had to buy an extensive list of supplies at the request of the hospital. They also asked for help and received donations on TikTok, Instagram and X to get it done. However, the money they spent failed to be a guarantee for their son’s surgery.

The third time that their son was taken out of the scheduled surgery to make room for patients who allegedly had paid for private appointments to have surgery in the hospital, Luisana took to social media. She bemoaned the situation to Attorney General Tarek William Saab. Her video, recorded in the health center, became viral the day it was posted. The hospital’s director, Pedro Salinas, reached out to her 48 hours later. “He said to me: ‘Mrs. Luisana, you have no idea the damage you've caused me with that video’. So I replied: What about the damage done to my son?”.

Braian had surgery on October 18, 2023. When he was released from the hospital, staff refused to give Luisana the files and medical records pertaining to Braian’s surgery, all of which she had requested. This was the aftermath of an inquiry by the Public Ministry on the irregularities of inappropriate charges in the operating rooms at the hospital in Naguanagua that had been exposed by Luisana.

Before leaving the hospital, two prosecutors asked Luisana to record a new video thanking the authorities for his son’s surgery. She accepted, even though she made it clear that her son required two major surgeries and only got one. The tumor that compromised his right eye vision was not extracted.

Regarding the pending surgery, Braian’s parents have run out of resources. They have more questions than answers: “How many doctors do I have to report for my son to be cared for? I have to do this again to get his eye surgery?”, Luisana wonders. She posted another video in February this year asking the authorities for help. As of the deadline of this investigation, her request had not been answered.

In the end, the director of Hospital Oncologico Dr. Miguel Perez Carreño in Naguanagua, was removed. Luisana has tried to contact the prosecutors to get to know the details of the judicial investigation, to no avail. “The prosecutors vanished. There is no ongoing investigation. Unfortunately, I have to post on social media because that is what seems to bother them the most. That is how it works here in Venezuela.”

CHARGES OVER THE RIGHT TO HEALTH

Maracaibo is the second most populated city in the country and the capital of the state of Zulia. There, patients are also charged fees to use operating rooms at public hospitals. Carmen Huerta, a 33-year-old woman, took four months to collect the money she was charged to have gallbladder surgery at Hospital Universitario de Maracaibo.

In October 2023, doctors found several gallstones in an appointment. After her diagnosis, a man wearing hospital ID approached her and told her that she could have her surgery in a week if she paid in dollars. “He told me to write down a list of 12 things I had to take with me if I wanted to get surgery, and pay, because otherwise the waiting list was endless, he also said that if one of my gallstones moved I could have bile spillage and that it was dangerous.”

Four months later, in February 2024, she was able to collect 250 of the 300 dollars to get the surgery, which was now urgent due to the risk of bile spillage. “I got there and I had a bout of pain, I promised the man (who was the doctor’s contact in the hospital) that I would get the rest of the money for the next day. I was admitted and put on a stretcher, and they told me I would have surgery the next day. The pain was unbearable,” she explains.

Lying in her hospital bed, she recalled everything she had to do to collect the money. She took on additional classes in the school she works at with children aged 9 to 12, where she makes a mere 20 dollars a week – enough for food for her mother and her two daughters. She took out a loan, sold her kitchenware, bought a hair dryer and started offering hairdressing services to her acquaintances; she also cleaned homes and babysat kids in her community to get the extra money.

Money in hand, she arrived at the hospital and was taken to her room, where she waited for her surgery. She was there for only 12 hours. At 3 AM, a nurse and a doctor asked her to leave because an emergency had been brought in and her surgery needed to be rescheduled. “I begged them not to kick me out, that I would pay the rest of the money the next morning. But they kicked me out of the hospital anyway.”

Outside, carrying her small bag of belongings with toiletries and the supplies, Carmen had to wait in the dark for the day to dawn. She couldn’t go home, she had to walk across the city because there was no public transportation at that hour, and it was dangerous. She wept in front of the hospital. “I couldn’t tell if my tears were out of pain or injustice, or because of the nurse and doctor’s faces when they kicked me out,” she regrets.

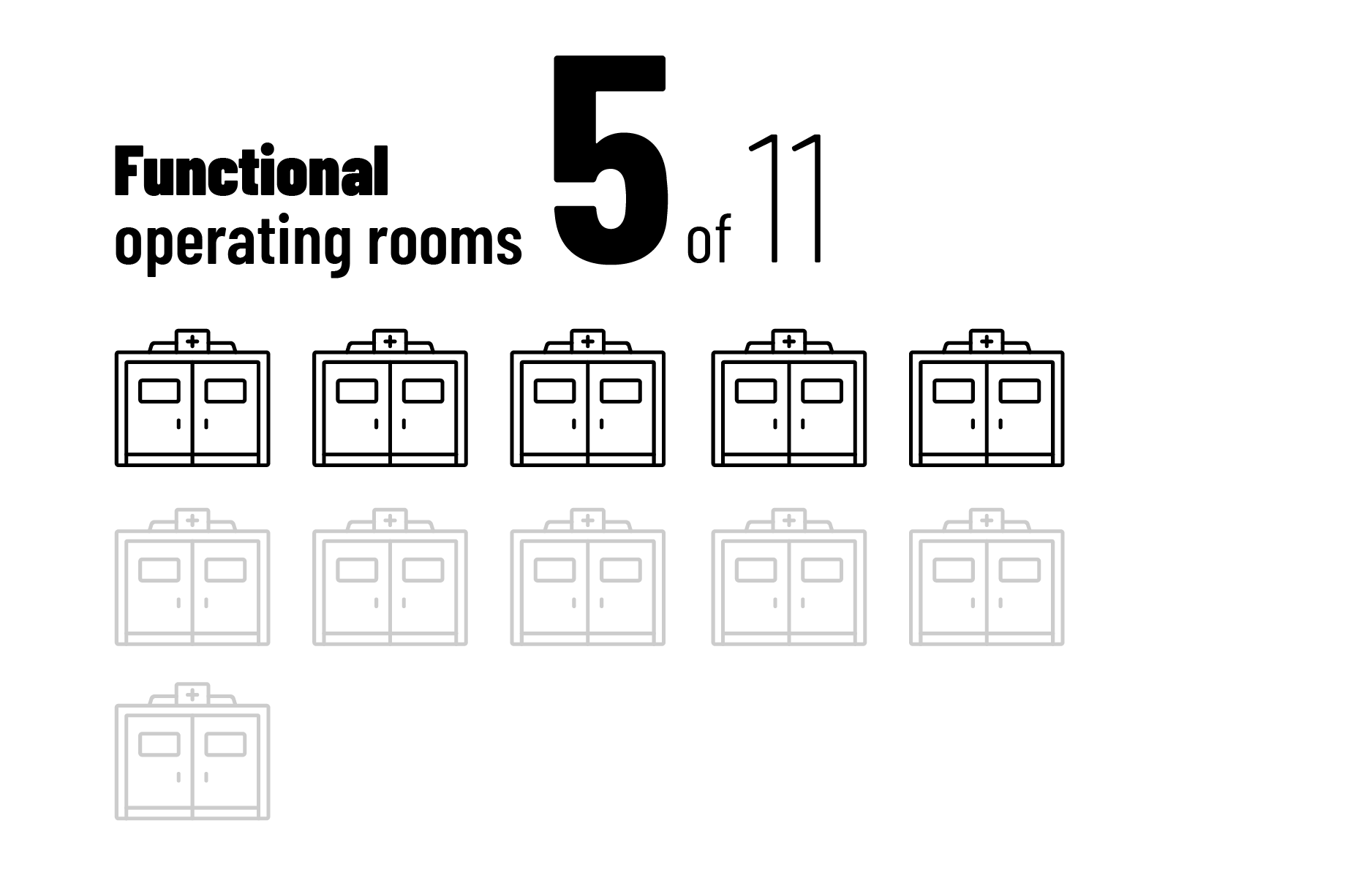

Hospital Universitario de Maracaibo, from where Carmen was thrown out, is the largest in the state of Zulia, and it has 11 operating rooms. However, only five of them are functioning, as stated by the president of the Nurses Association of that region, Hania Salazar, in November 2023.

An ER doctor at that hospital was on call the day of Carmen’s surgery. He had a single pair of gloves (bought with his money) to examine patients. “It’s impossible not to ask patients to bring their own supplies, at least in cases of emergency,” he said. The doctor refrained from speaking about the charges for surgery. This feature has decided to protect the identities of several sources, out of fear of reprisals from the government of Nicolas Maduro.

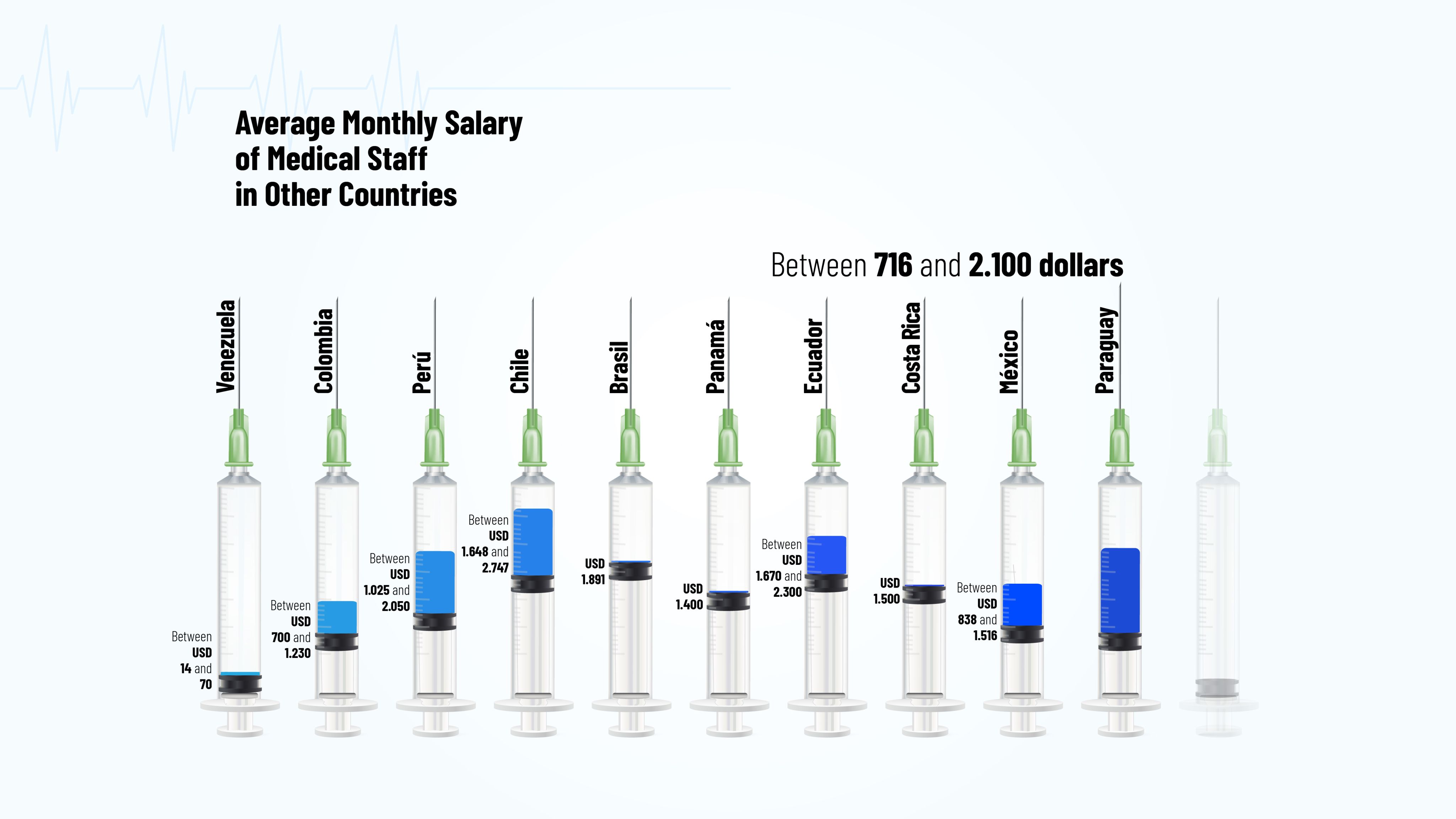

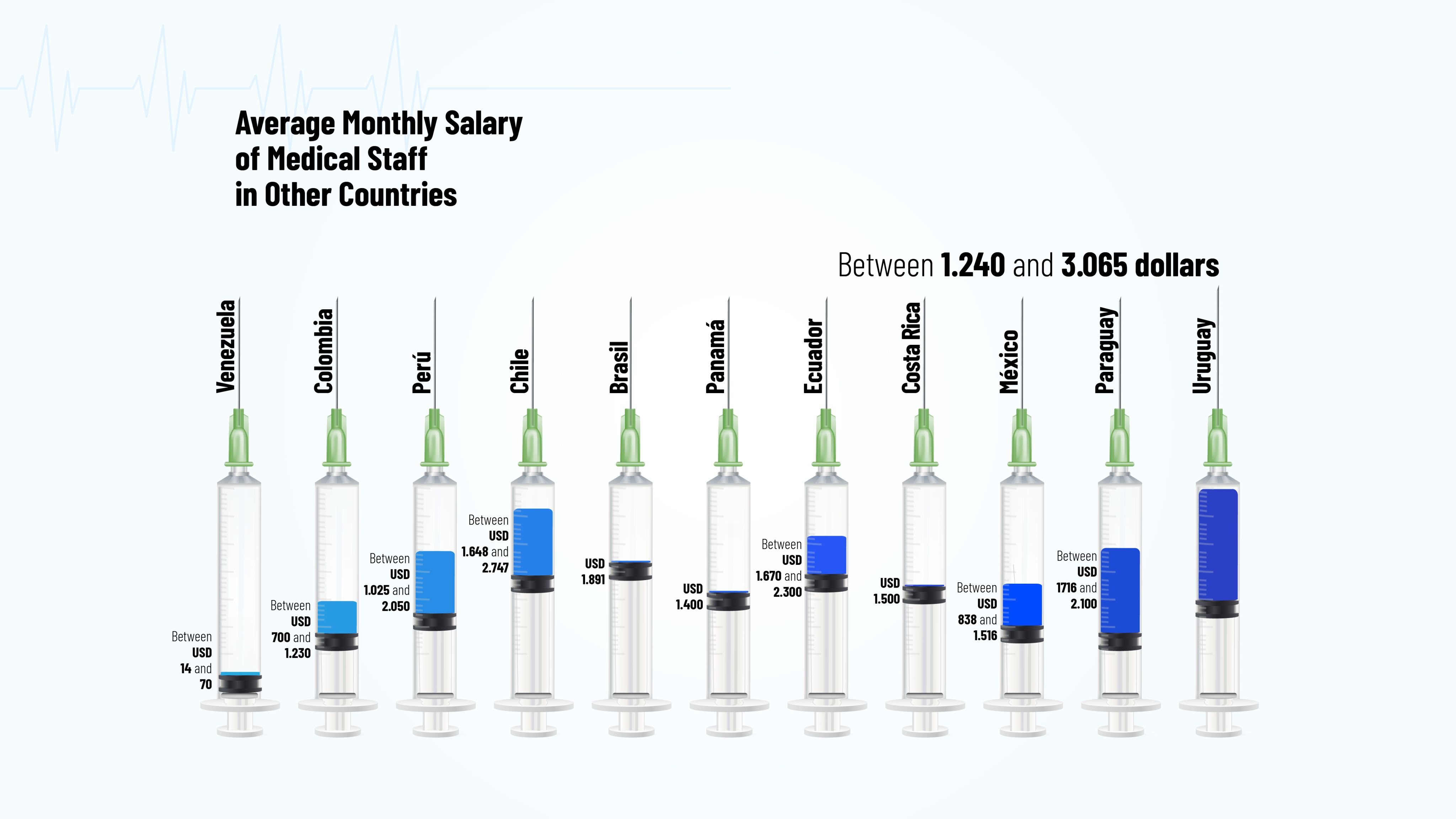

The shortage of supplies and equipment in health centers is typical of the complex humanitarian emergency in Venezuela (acknowledged by international organizations since 2016), and to make matters worse, staff is underpaid. This factor may drive corruption within hospitals, says Douglas Leon Natera, president of the Venezuelan Medical Federation (FMV). Health practitioners in State-run institutions are expecting the renewal of the collective contracting scheme that establishes improvements in payment and social security for the sector since 2003.

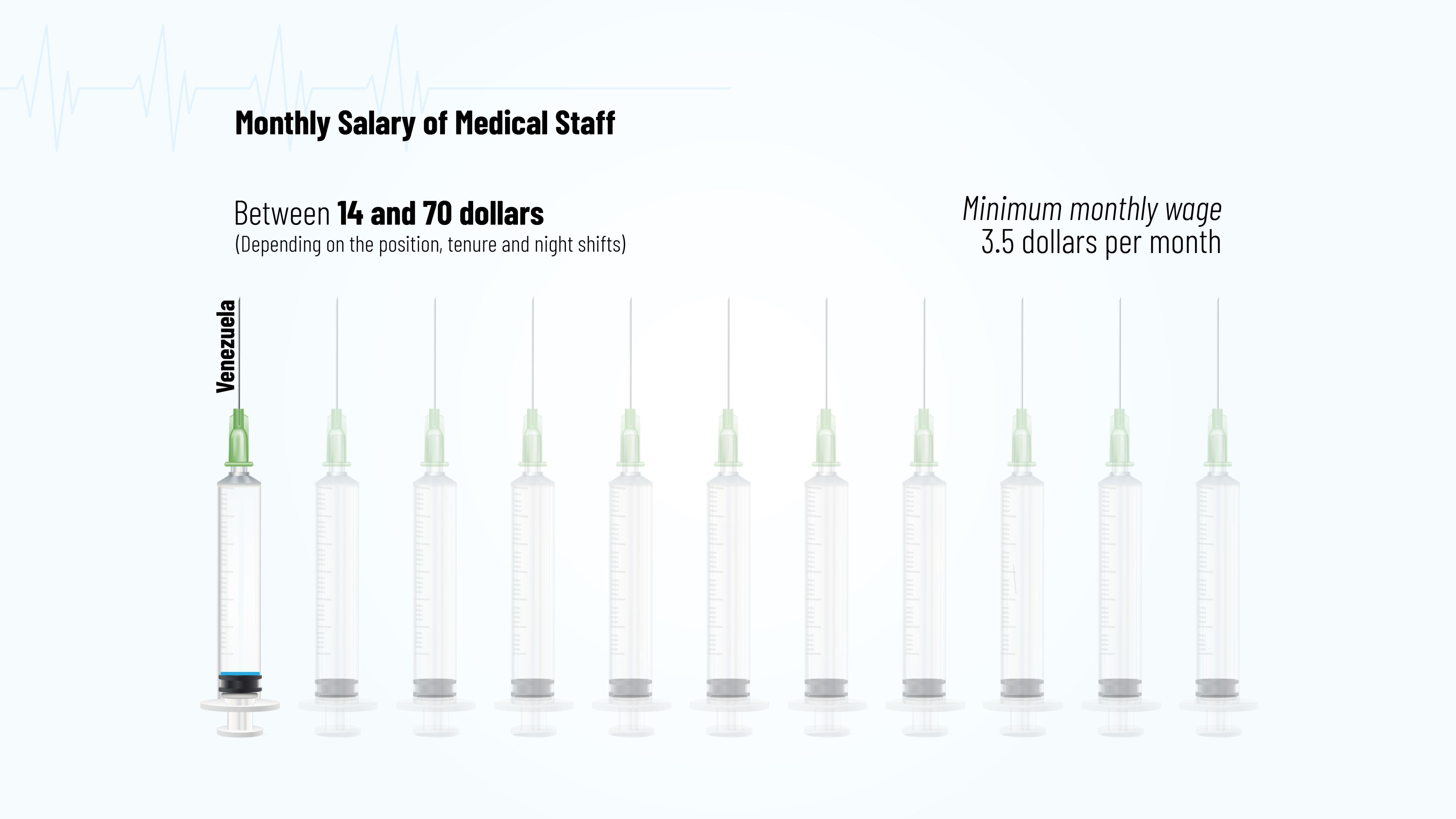

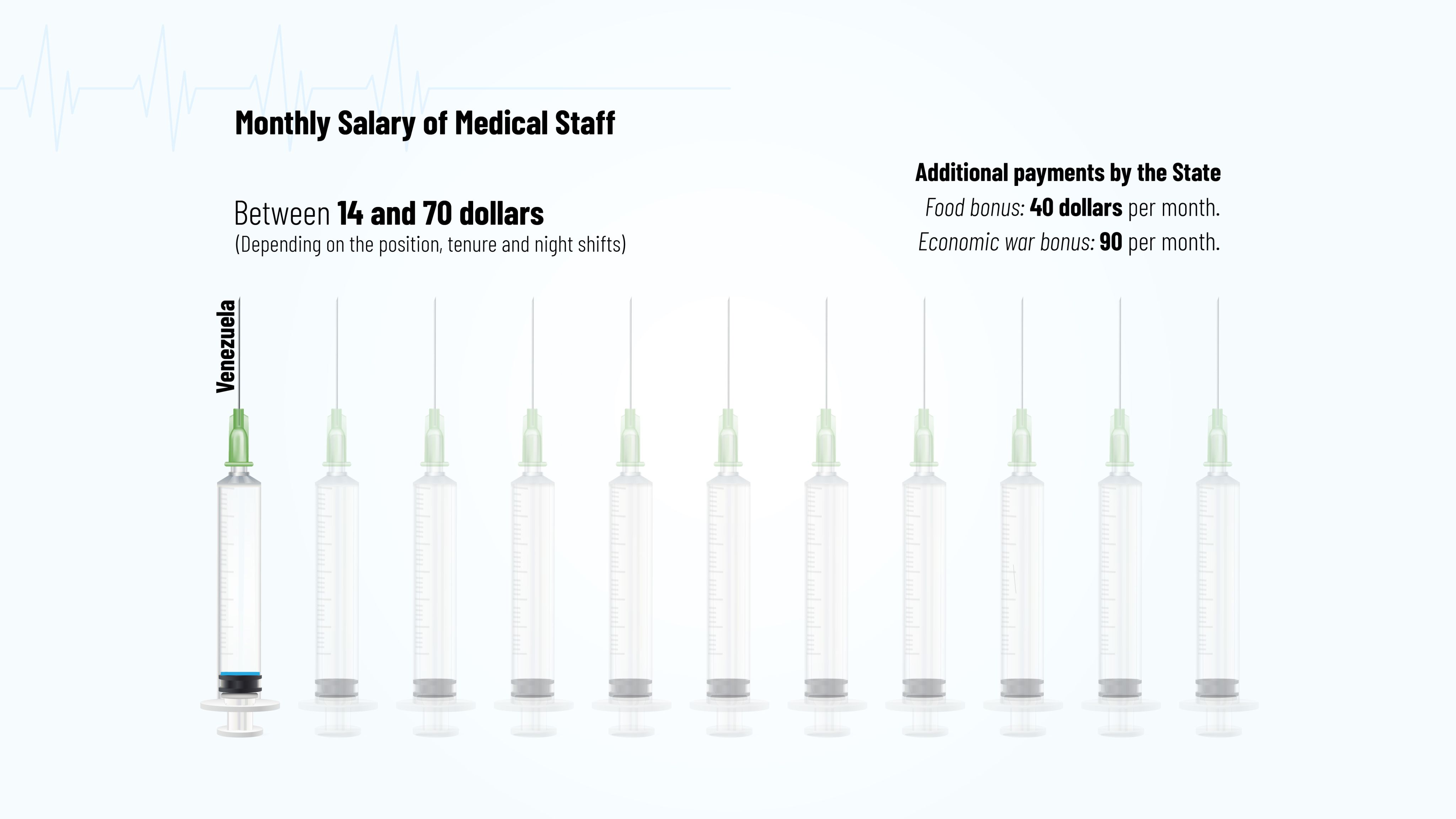

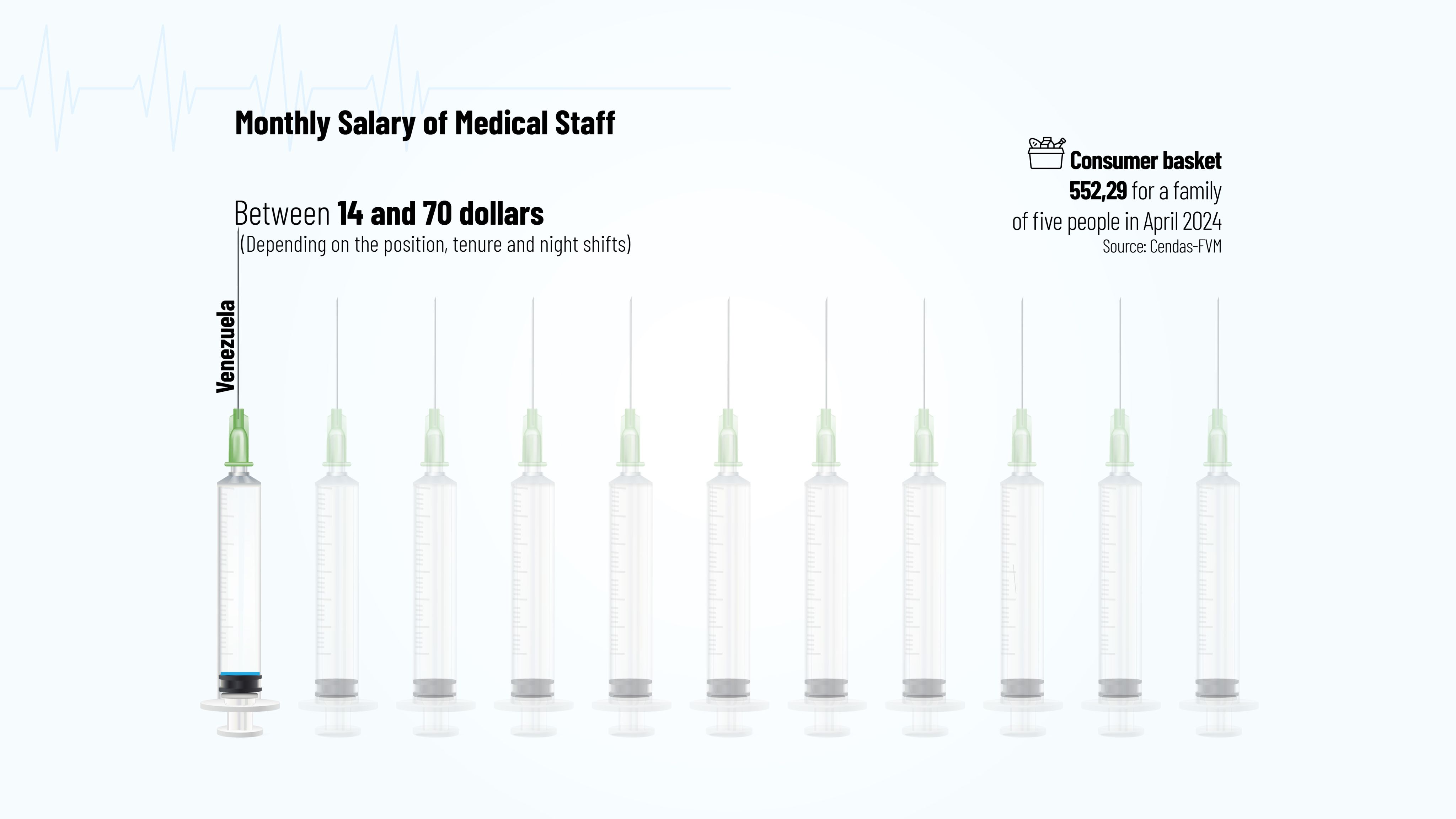

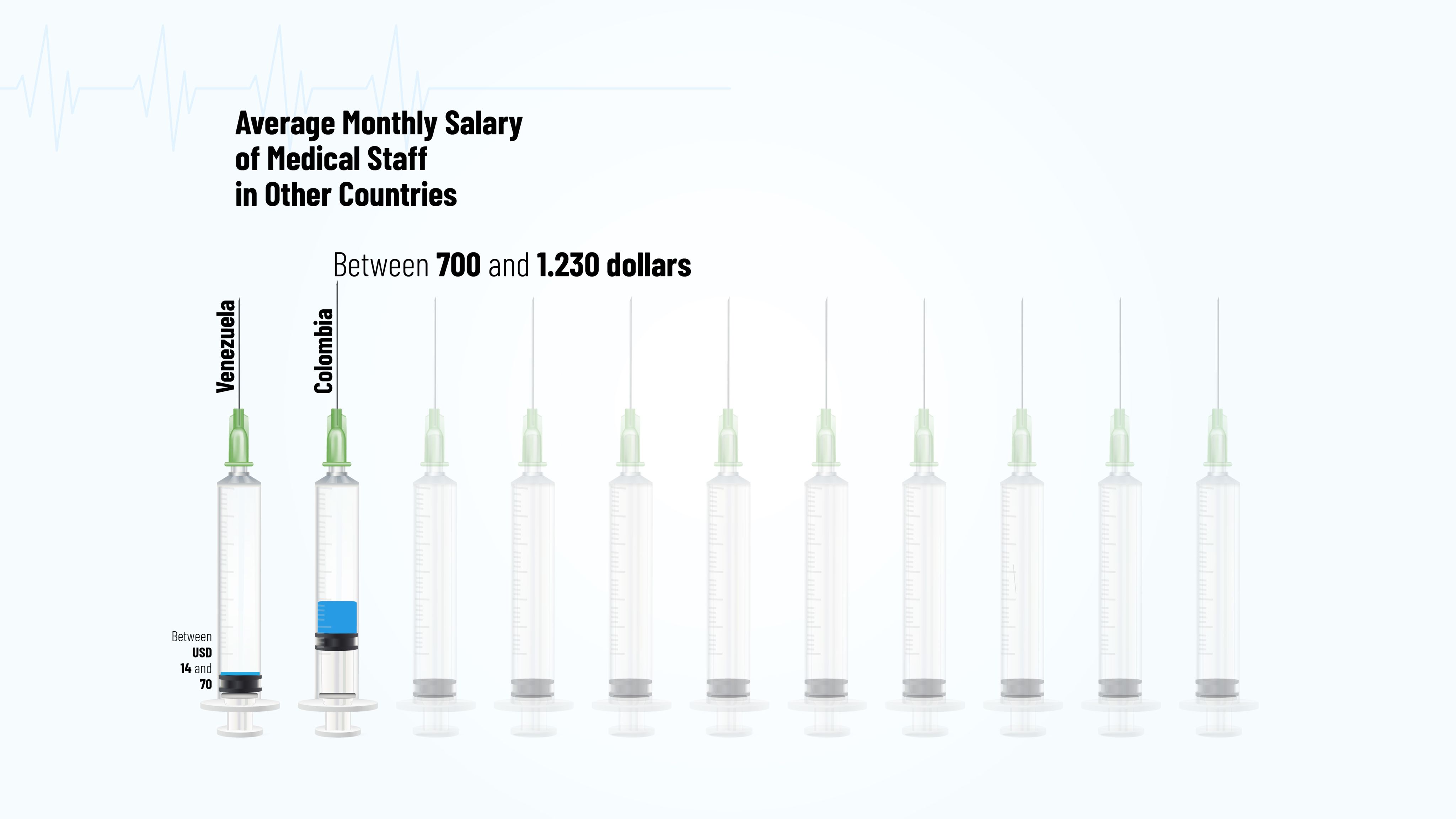

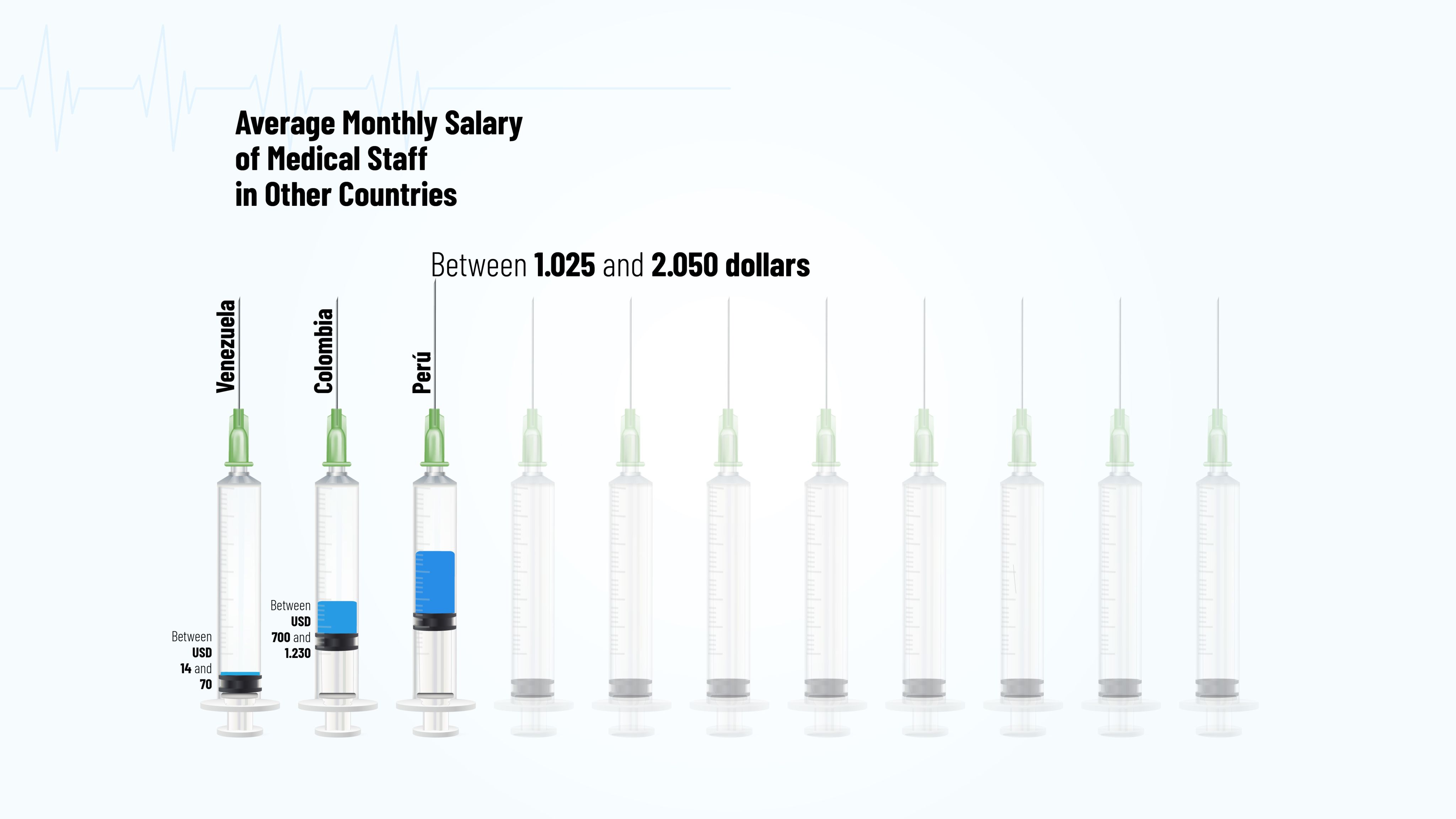

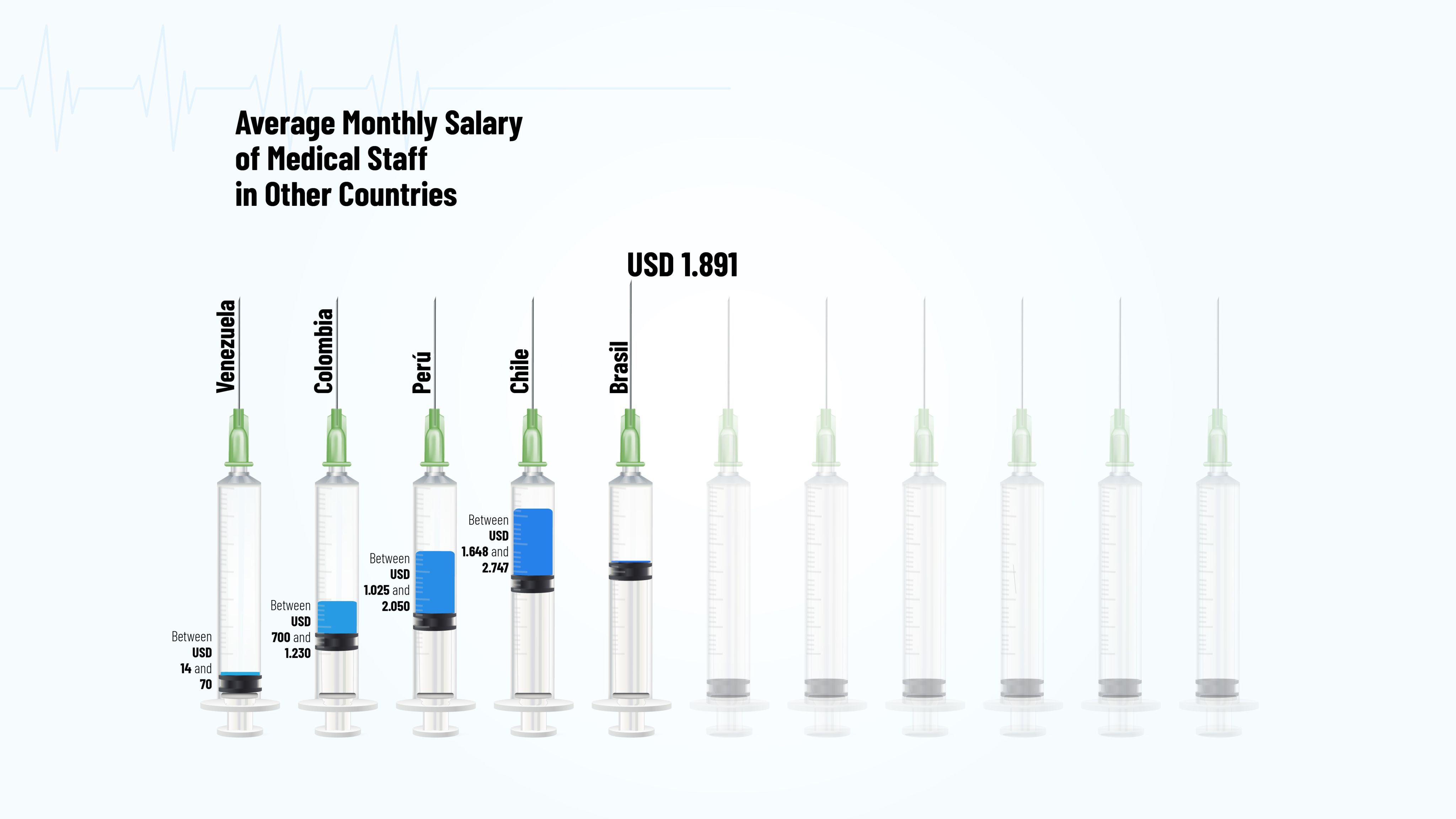

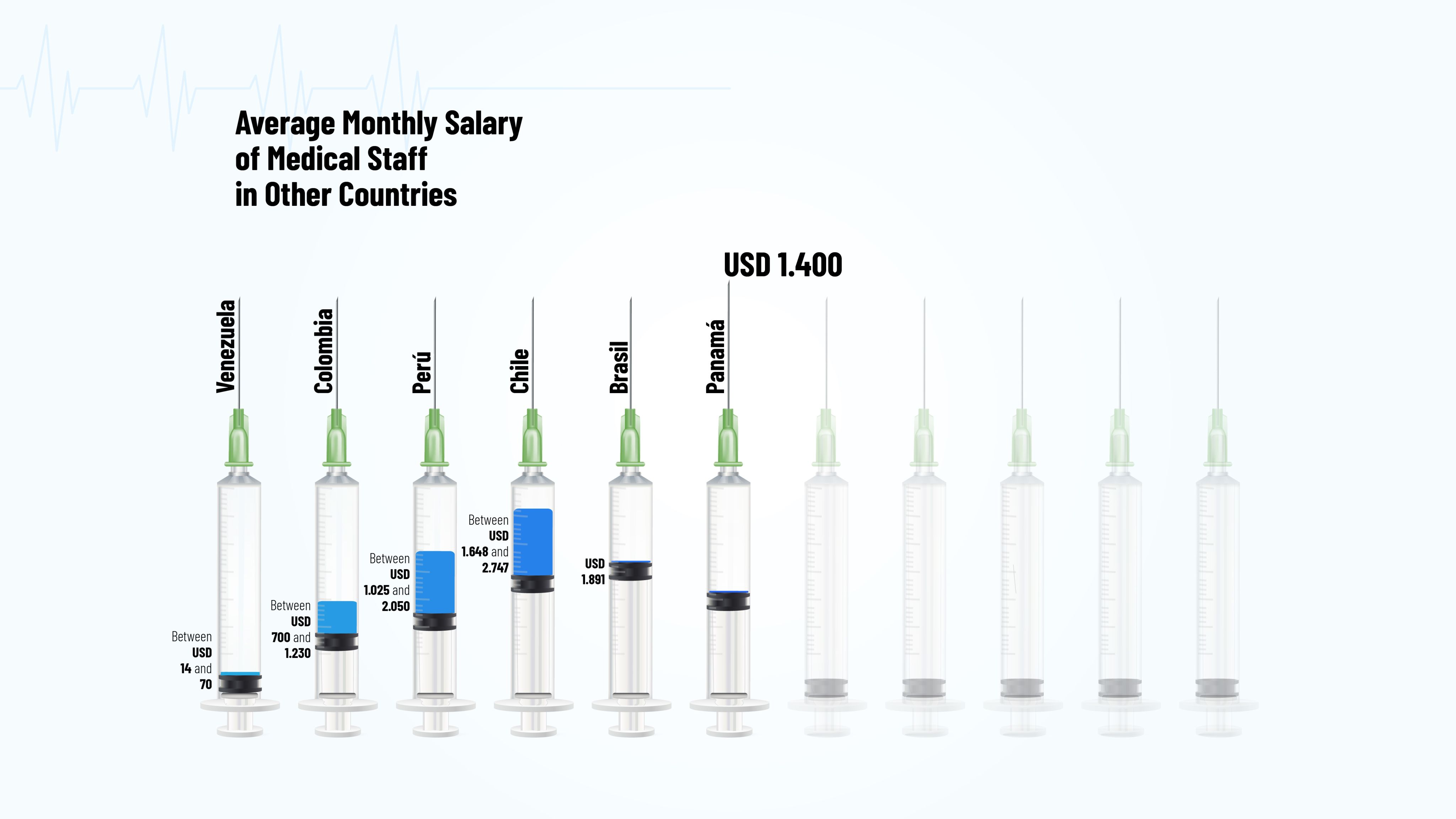

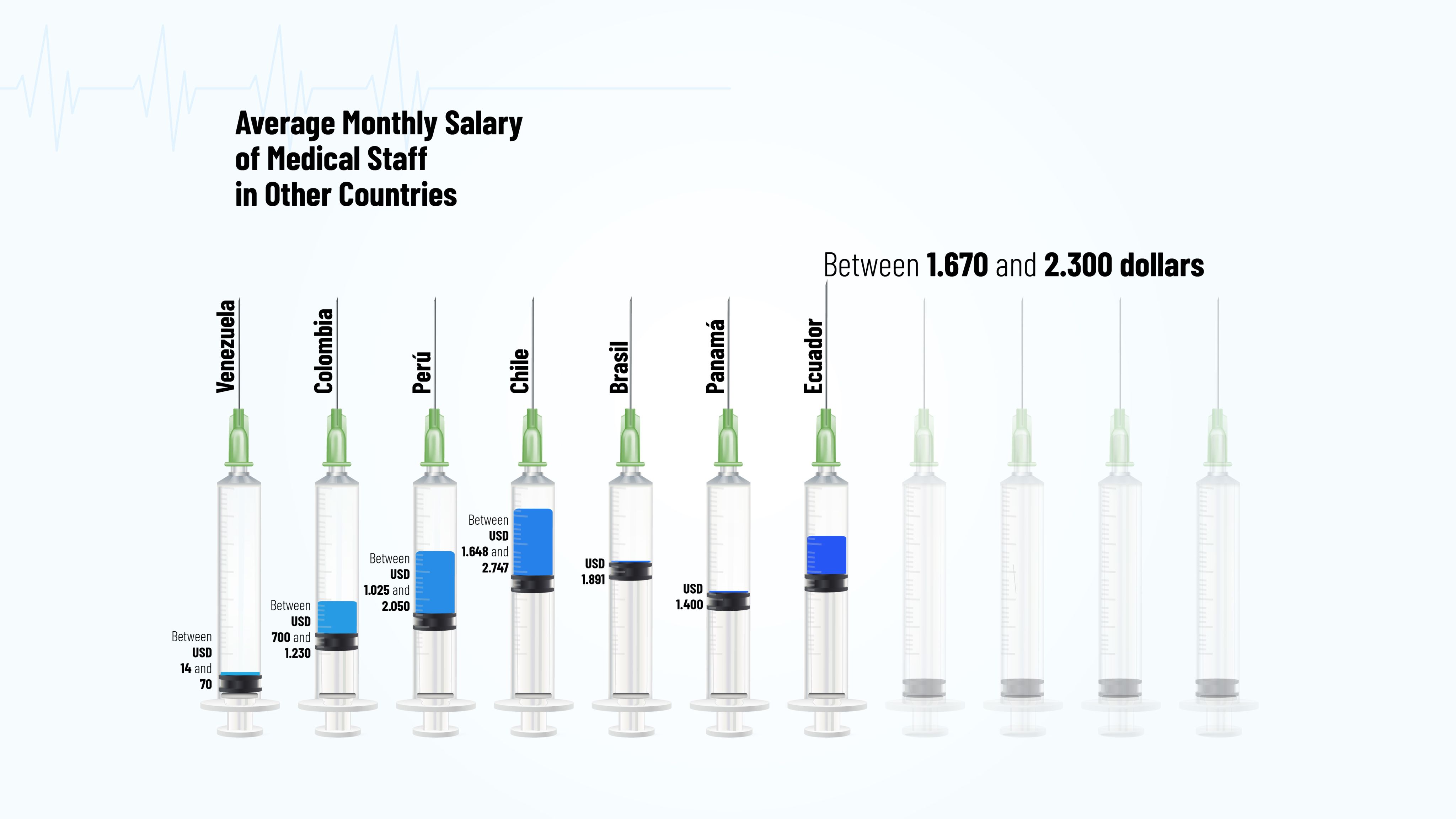

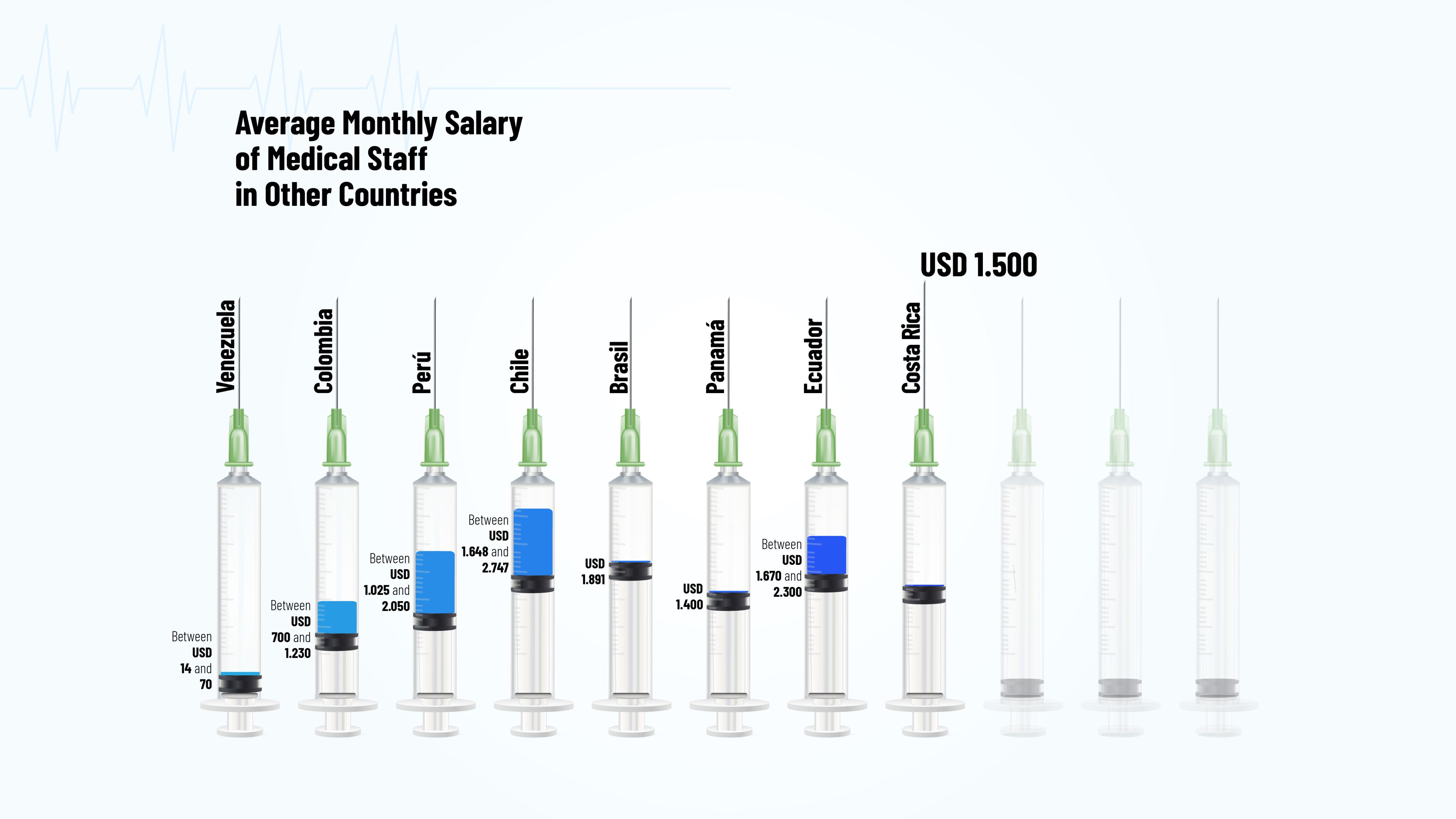

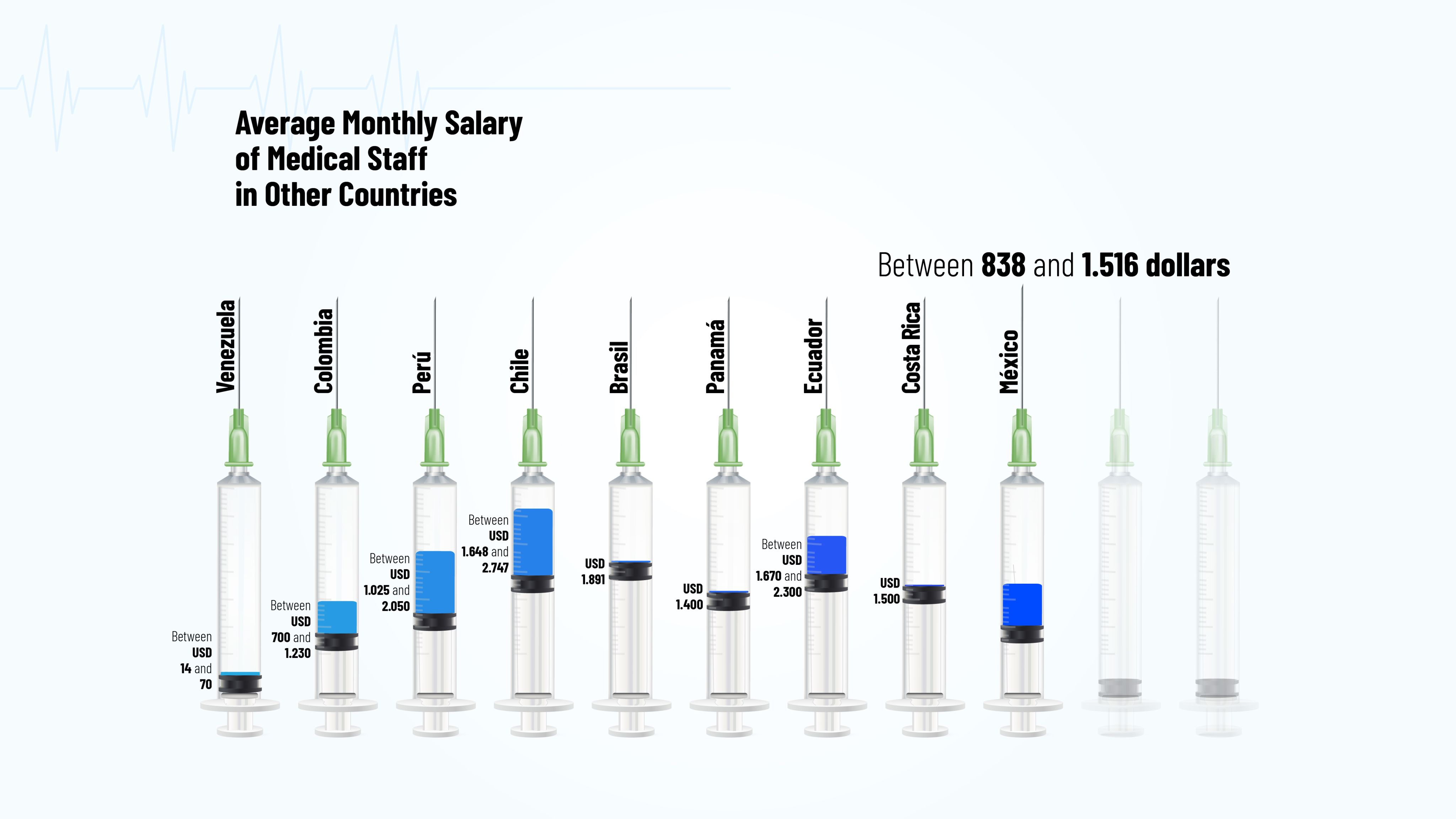

In the last decade, doctors and nurses have led protests to decry the devaluation of their salaries: In 2020, a hospital employee earned a monthly salary ranging between 15 and 30 dollars.

In March of 2022, the executive branch set the minimum salary at the equivalent of 30 dollars, but with the devaluation of bolivares, the country’s legal tender, they lost purchasing power. In January of 2024, Nicolas Maduro issued a decree to increase bonuses to 100 dollars per month for public officials, including the healthcare sector. In May that year, he passed another increase of 30 dollars. Still, the salary of State doctors remains low in comparison with other countries in the region. The compensation of a Venezuelan doctor is equivalent to a fourth of the minimum wage of a Colombian employee.

Five sources in the field of healthcare: two union leaders, a nurse, a former director of a hospital, and a traumatologist (who asked to keep their names confidential for security reasons) stated that inappropriate charges, especially in surgical services, have been fueled by low salaries.

Inappropriate charges became more conspicuous in public hospitals in Venezuela following the COVID-19 pandemic, according to testimonies collected by El Pitazo in three cities: San Cristobal, Acarigua and Caracas. “My sister was admitted with COVID to Hospital Clinico Universitario de Caracas. We paid for the supplies, and for a nurse to care for her and guarantee she did get her medication. We were not the only ones. There were around ten patients in the COVID area, and they all had paid,” recalls Mariela Perez, whose sister Maritza was hospitalized for a month and died of COVID in 2021.

Even though national legislation forbids this type of practice, the business of inappropriate charges in public hospitals hasn’t stopped growing since the pandemic – to the point in which it opens or closes the doors of operating rooms.

Articles 20 and 122 of the Medical Deontology Code, mandatory in Venezuela, explicitly forbid any sort of negotiation or payment in exchange for services in the public healthcare system or transfers to private hospitals. Likewise, the Anti-Corruption Law (in place since 2003, and amended in 2022) sets forth penalties of two to six years in jail for officials who abuse their powers as means to get money or bribes. This regulation applies for employees of organizations incorporated with public funds, i.e., hospitals.

Two doctors and a nurse working in hospitals of the District Capital and the state of Falcon, explained that in public health centers, small groups come together to organize networks to make money with the operating room and scheduled surgeries. Patients may be contacted in private practice appointments or in hospitals.

In the meantime, Carmen is waiting for her surgery to be scheduled. She hopes her right to health prevails, despite not having the money to pay for it. She spent the money she had saved to treat a fungus on her mother’s skin, and in other emergencies with her daughters.

But Carmen’s pain persists. “In order to prevent pain, I don’t take deep breaths. Some nights I pace around the house because I can’t take it. I keep an eye on the color of my urine, as the doctor said. And I keep trying to collect the 300 dollars. I have even thought about selling my home.” Carmen lives in a popular sector that doesn’t have all of the utilities, and her house could sell for 1,000 dollars.

SURREPTITIOUS ALLIANCES

Consequential to the devaluation of the income of practitioners employed in Venezuela’s healthcare system are the commissions paid to hospital directors or staff by commercial houses. These companies offer money for each referred patient that rents or buys equipment or surgical supplies from them, as per the people interviewed by El Pitazo for this feature.

The surreptitious alliances directly affect patients. For example, the case of a coach in Los Teques, capital of the state of Miranda, who had a brain hemorrhage in October 2023. His wife found him unconscious on the bathroom floor, she asked for help to take him to the nearest hospital, Victorino Santaella. There were no specialists in neurosurgery there that day, so he was taken to Hospital Dr. Miguel Perez Carreño in Caracas, 34 kilometers away from their city.

The man, 48, had no health insurance to be treated in a private center. Neither him nor his family knew what they were up against; he required treatment and a surgery called aneurysm clipping to stop the brain’s bleeding.

This procedure needs to be done 24 to 72 hours after the bleeding to prevent further complications. If the patient is not operated on during that time frame, a 21-day stay in the hospital is necessary for observation, because the risk of death increases due to the bleeding and the swelling and pressure on the skull.

“I was hospitalized for three months and a half before the surgery, while we collected the money to pay the commercial house for the rental of the equipment,” the coach says. His waiting time was four times longer than recommended because the neurosurgery department at Hospital Miguel Perez Carreño didn’t have a cranial drill, a specialized equipment to undertake the intervention.

The patient was told by the staff to rent the equipment and purchase the supplies from a private company for more than 3,300 dollars. “They told us it had to be with that company or that there would be no surgery at all. In fact, some nurses told us: ‘You are not considered human beings here, you are body count for the business’,” he adds.

“A clip costs 400 dollars and (this particular commercial house) sells it for 750 dollars. We kept asking if we could buy it somewhere else and they kept saying no. The patients had a conversation and we protested, but there was nothing to do. If we kept insisting we would lose anyway because they wouldn’t provide the service or treat us badly,” the coach recalls. His family members took the matter to the hospital director, but there were no answers given.

He is not the only patient that has been forced to get his equipment and supplies from a specific private company. A public official who also needed to repair a brain aneurysm spent five days in hospital without chances to get the surgery. Her family had no means to collect more than 2,300 dollars to cover the expenses, and she had to resort to government aid to be operated on. Her surgery was held in early 2024 with a cranial drill that the State acquired for the Hospital Dr. Miguel Perez Carreño.

Stories such as these ones are commonplace. “This is a national phenomenon,” said a doctor with more than 25 years of experience in public health centers and employed in the surgical area at Hospital Dr. Jose María Vargas in Caracas. This hospital works with a short-list of seven authorized companies to rent or purchase specialized material, according to a file that was made available to El Pitazo and CONNECTAS. Healthcare authorities didn’t respond to our requests for public information as of the deadline of this investigation.

In April 2024, two senior patients admitted at Hospital Jose Maria Vargas in Caracas with hip fracture managed to collect the supplies required for their surgeries. However, the directors and the traumatology department didn’t go on with their scheduled surgeries because they had purchased the supplies on their own and not with the companies that patients are instructed to do so. The supplies were in suitable condition and complied with the indications, but the hospital refused to accept it, two internal sources stated.

One of the patients, Sara Santaniello, 84, was at risk for the delay in the intervention. She was hospitalized for 93 days, and she had an urinary tract infection while she was there. Twice she was told she would be operated on, but it didn’t happen. “On April 1 she was abruptly released from the hospital without a medical report explaining her condition. There was no reason, they only told her to return in 10 days. She left the hospital with a leg that was five centimeters shorter than the other, and this meant she was not eligible for surgery, as a doctor explained later,” says an acquaintance of the patient.

Sara was shocked that she couldn’t have surgery and at the prospect of walking with difficulty. She refused to eat and complained daily. Her family reached out to the directors of Hospital Jose Maria Vargas and the surgery department to see if there was something to be done. They said no. Sara decompensated and she died at home, 21 days after her release.

The other patient, 74, (whose identity can’t be revealed) had been in bed for 11 months because she needed a hip prosthetic implant to walk again. Her family in Portugal and her neighbors collected the money to buy it for her.

“Everything was ready for the surgery, then the traumatology director and the surgical department didn’t go on with it because the prosthetic implant was not purchased from the commercial houses authorized by the hospital. When you tell a person that her medical service depends on a purchase made at a certain place, that is coercion. Patients may buy supplies wherever they want, as long as they comply with the requirements,” says a doctor of Hospital Dr. Jose Maria Vargas, who is against this illegal practice.

The patient was able to purchase the prosthetic implant ten months after the fracture. She paid 600 dollars for it, less than half of the 1,478 dollars that one of the commercial houses authorized by the hospital was asking.

Doctors denied her access to an operating room, but her family members filed a denunciation with the media and two State agencies visited the hospital to interrogate the parties involved. The patient had her surgery following this visit. The hospital’s director asked the patient to sign a voluntary statement of medical services and supplies’ gratuity, in which she certifies that she was not asked to pay compensation for the medical care she received.

The patient with hip fracture admitted at Hospital Vargas in Caracas had to sign a voluntary statement of medical services and supplies’ gratuity prior to her surgery, even though she was initially coerced to purchase the prosthetic implant from a private company authorized by the health center | Photo: Courtesy of the relatives of the patient in Hospital Jose Maria Vargas

The patient with hip fracture admitted at Hospital Vargas in Caracas had to sign a voluntary statement of medical services and supplies’ gratuity prior to her surgery, even though she was initially coerced to purchase the prosthetic implant from a private company authorized by the health center | Photo: Courtesy of the relatives of the patient in Hospital Jose Maria Vargas

STATE-ENDORSED MALPRACTICE

Data indicates that inappropriate charges are on the rise. A survey conducted by Observatorio de Universidades (OBU) found that 18% of the consulted residents and interns had witnessed illicit trade of medical materials and supplies in 2022, while 38% claimed they were not aware of it, explains sociologist Carlos Melendez, coordinator of the organization that monitors the studying and living conditions of university populations in 110 municipalities of 23 states and the District Capital.

Melendez mentions that the practice of inappropriate charges had an upsurge since 2021. His statement is based on the results of his organization’s annual survey, which evidenced an increase in reports of illicit trade of medical materials in hospitals. “The State’s absence endorses it, and it ends up legitimizing the resulting corruption networks,” he explains.

Attorney General of the Republic Tarek William Saab held a meeting with Minister of Health Magaly Gutierrez in May 2022 to investigate crimes in the public healthcare system | Photo: Courtesy of X @TarekWiliamSaab

Attorney General of the Republic Tarek William Saab held a meeting with Minister of Health Magaly Gutierrez in May 2022 to investigate crimes in the public healthcare system | Photo: Courtesy of X @TarekWiliamSaab

Even though the FMV is in charge of regulating medical practice, its President Leon Natera claims that the agency does not have any information pertaining to those judicial investigations. It has not received notifications or subpoenas to contribute to the national inquiry that was opened by the Public Ministry in 2021 to impose sanctions on people accused of illegal charges in exchange for medical care in hospitals.

“We are not certain about these inappropriate charges, but there are rumors running around: charges by doctors, nurses and other staff,” as he adds that “inappropriate charges are reprehensible and condemnable, wherever they come from.”

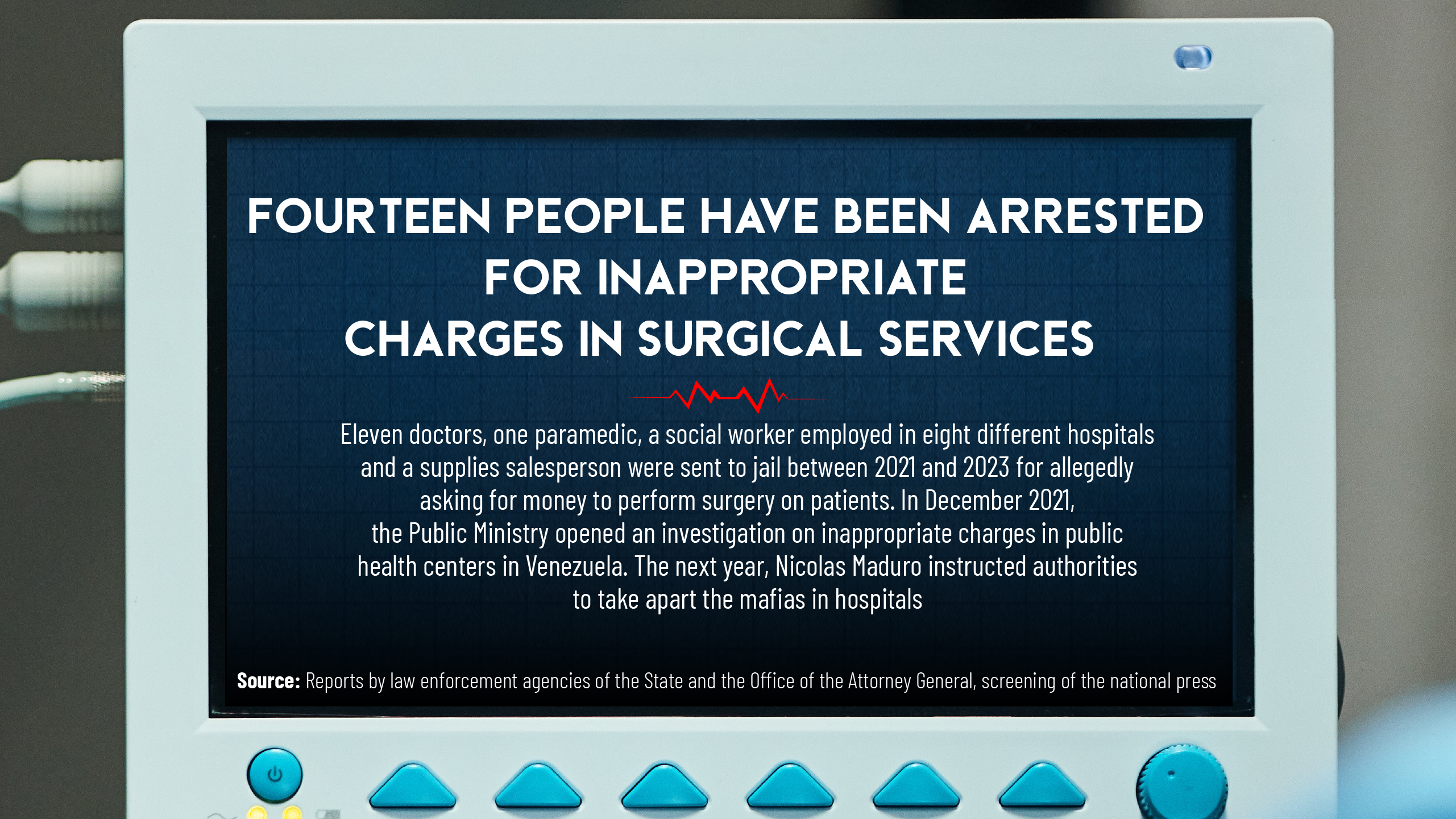

Some cases of inappropriate charges have had a response by the authorities. From 2021 to 2023, the State law enforcement agencies reported the arrest of 14 people, including doctors, nurses and usurpers in the healthcare sector. They were arrested for alleged illegal charges to access operating rooms in hospitals in Caracas and eight states of Venezuela: Apure, Barinas, Carabobo, Lara, Tachira, Trujillo, Vargas and Zulia, as per data collected for this feature in releases of police and military agencies. Yet the official response is not enough for the magnitude of the problem, consulted experts agree.

Hospital I Roque

Alvarado, in Encontrados

State: Zulia

Agency in charge of the proceedings: National Police (PNB).

People implicated: Stanley Jaramillo, Yohana Tomasa and Vicmary Fernández.

...

The Police arrested two doctors on call and a supply saleswoman for charging 500,000 Colombian pesos (140 dollars) to a sergeant of the Armed Forces of Venezuela for a curettage, following a miscarriage. Doctors “had illegally seized the baby’s corpse as guarantee for the payment,” read the police report.

Source: https://epthelinkdos.online/occidente/zulia-medicos-cobran-500-000-pesos-a-joven-por-operarla-en-un-hospital/ http://jca.tsj.gob.ve/DECISIONES/2021/SEPTIEMBRE/589-23-C02-64875-2021-251-A-21.HTML

Maternity ward Julia Benítez

of Malpica Hospital

State: Carabobo

Agency in charge of the proceedings: Municipal Police of Guacara.

People implicate: Karla Ruíz.

...

The doctor was arrested for charging patients to perform c-sections in the health center.

Source: https://www.instagram.com/p/CaNj0SKvYBV/?igshid=MzRlODBiNWFlZA==

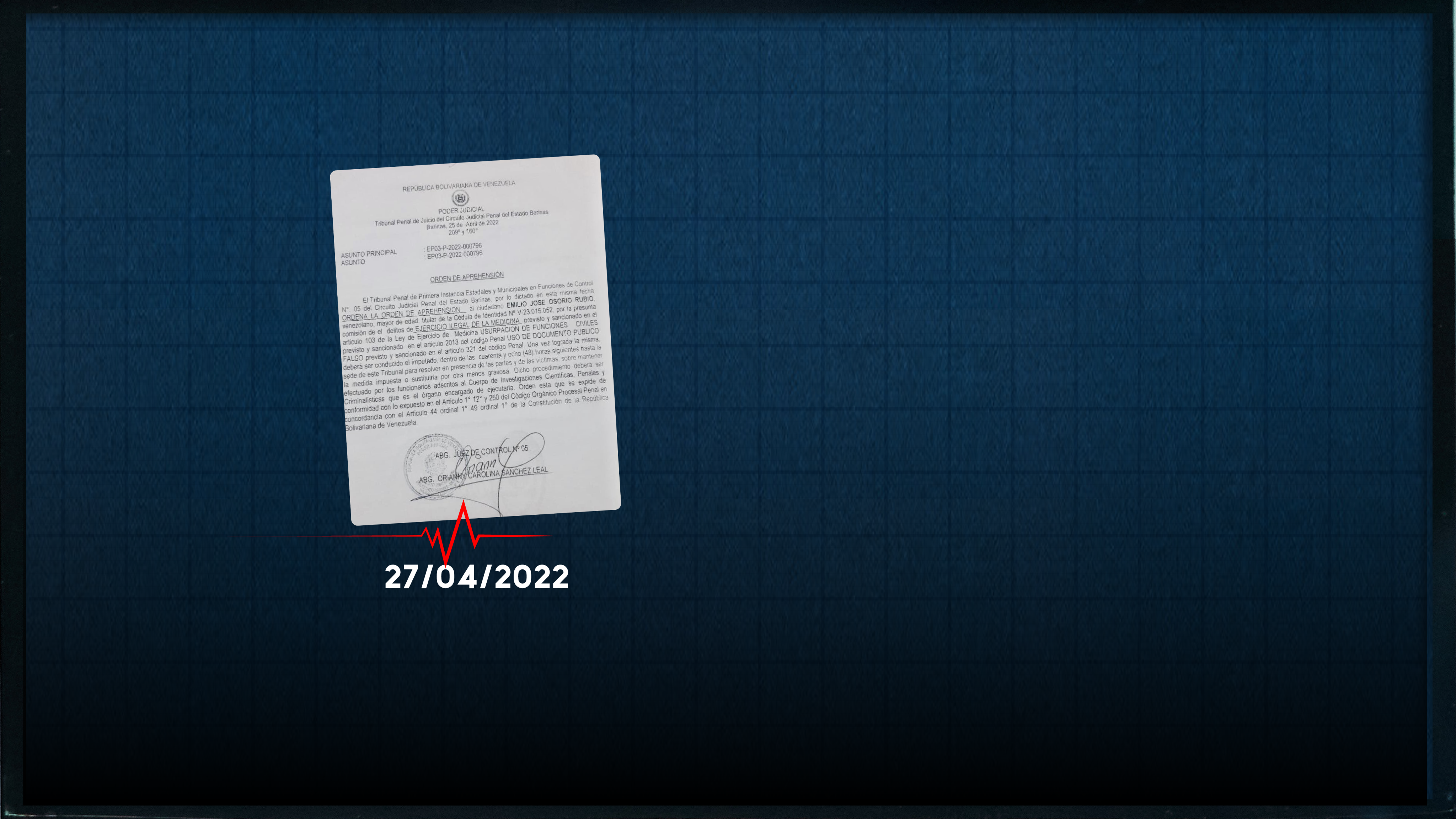

Non-specified

State: Barinas

Agency in charge of the proceedings: Public Ministry.

People implicated: Emilio José Osorio Rubio (arrest warrant issued against him).

...

Fake doctor accused of damages to an undetermined number of people in exchange for illegal fees.

Source: https://twitter.com/TarekWiliamSaab/status/1519324786345877504?s=19

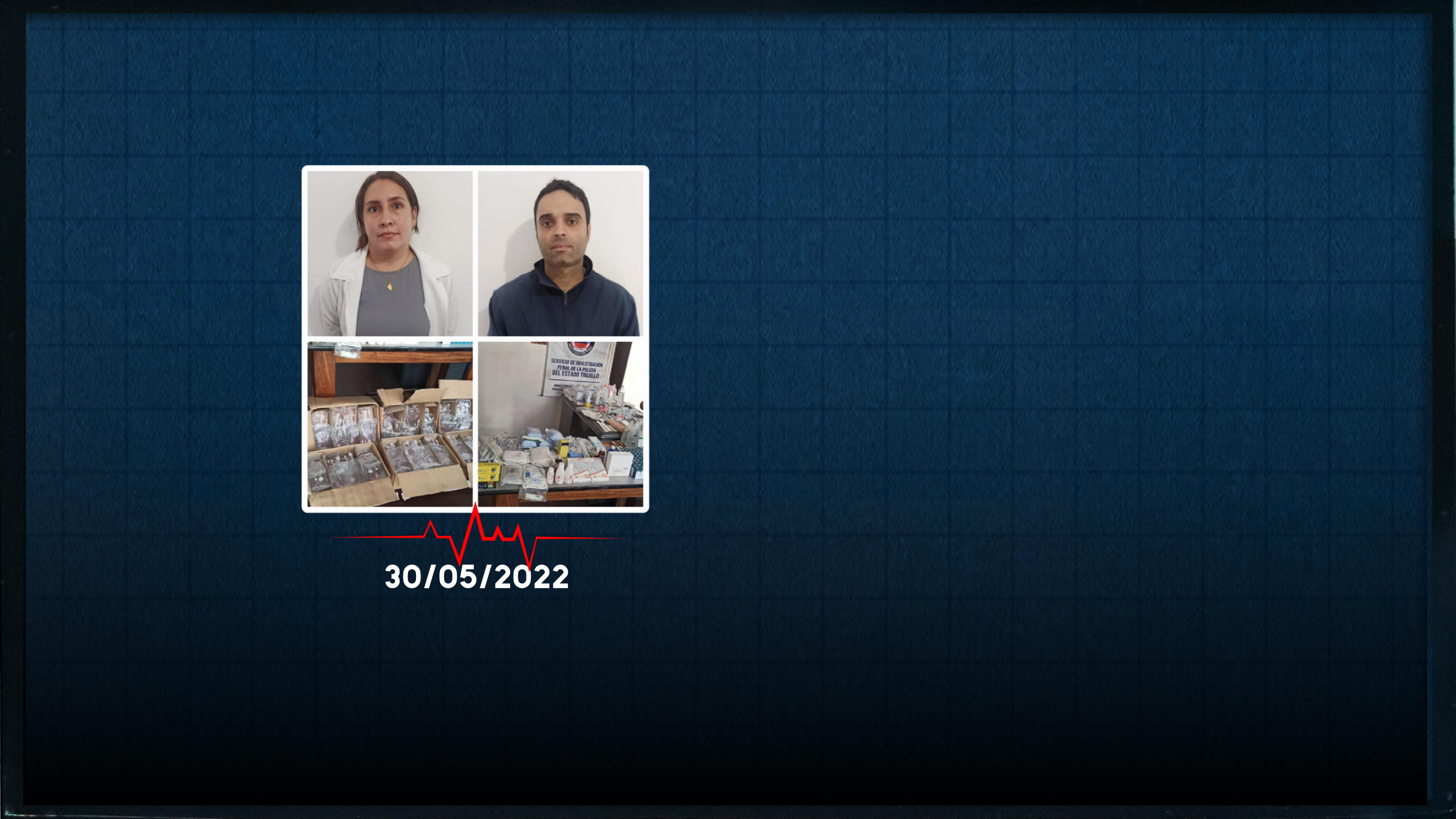

Hospital Pedro Emilio Carrillo

State: Trujillo

Agency in charge of the proceedings: National Police (PNB).

People implicated: Juan Suárez and Karelis Montilla.

...

Suárez and Montilla requested 300 dollars from the accuser to operate on her brother. A “large amount of supplies stolen from the hospital” were confiscated in a raid to their homes, according to the official version.

Source: https://www.eluniversal.com/sucesos/127655/detiene-en-flagrancia-a-dos-medicos-por-cobrar-en-divisas-en-hospital-de-trujillo

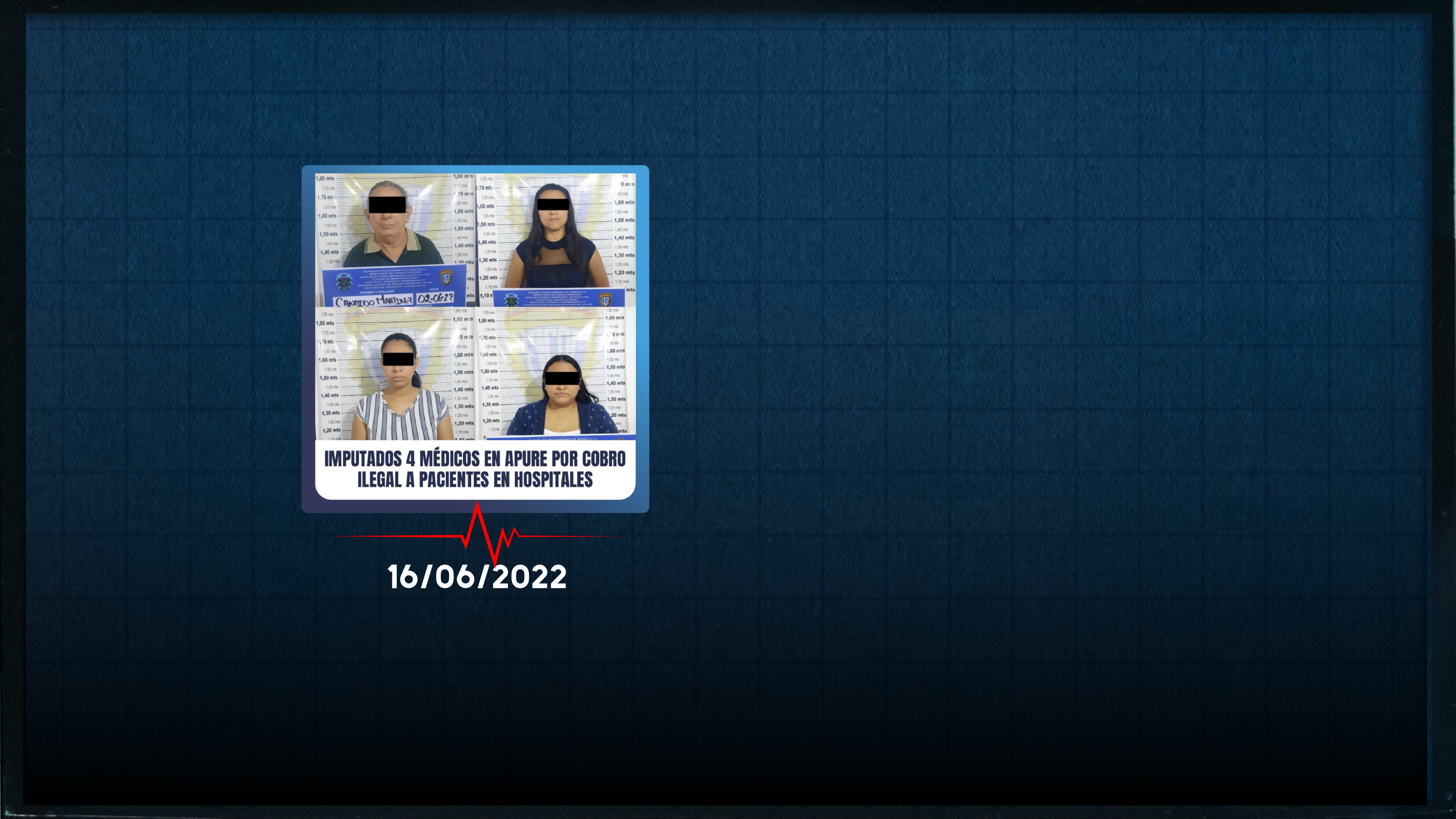

Hospital José Antonio

Páez, in Guasdalito

State: Apure

Agency in charge of the proceedings: Scientific, Criminal and Forensic Science Corps (CICPC).

People implicated: Cándido Alfredo Martínez Rodríguez (68), María Yaritza Vequiz Rumbos (35), Ana Yumar Rodríguez Hernández (35) and Ivis Dubarly Páez (37).

...

Two gynaecologists and two surgeons were accused by the Office of the Attorney General of inappropriate and unjustified charges to users in need of surgery, also of selling surgical supplies that were of free distribution.

Source: https://twitter.com/TarekWiliamSaab/status/1537609389561065472?t=s3dJZrO1lzGwSc7BxU3GRQ&s=19

Hospital General, in Táriba

State: Táchira

Agency in charge of the proceedings: Police of Táchira.

People implicated: P. Somaza.

...

The Public Ministry arrested the traumatologist after several denunciations of inappropriate charges in exchange for surgery in the hospital. The doctor was accused of demanding money from patients to bypass the waiting list.

Source: https://puntodecorte.net/detienen-a-medico-senalado-de-cobrar-en-divisas/

Hospital General

Dr. Miguel Pérez Carreño

State: Distrito Capital

Agency in charge of the proceedings: National Police (PNB).

People implicated: Jaime José Godoy Azuaje.

...

The implicated doctor worked in this health center and charged 800 dollars to patients to perform surgery in the institution, according to the authorities.

Source: https://www.instagram.com/p/ChKmkn6LTn1/?igshid=MDJmNzVkMjY%3D

Hospital Central Universitario Antonio María Pineda

State: Lara

Agency in charge of the proceedings: Police of the state of Lara.

People implicated: Sergio Fernández Delmoral.

...

The implicated paramedic pretended to be a cardiologist, family members of a patient reported having been charged 400 dollars by a doctor to arrange surgery.

Source: https://www.elinformadorve.com/08/02/2023/sucesos/polilara-detiene-a-falso-medico-que-cobraba-para-gestionar-intervenciones-en-el-hcuamp/?fbclid=IwAR3uQpGM9B5LC0x_G1duqGaQWQTi-XI61hQtBFGDKZHvCj91qQVTS0QIPic&=1

Hospital Rafael

Medina Jiménez (Periferico, in Pariata)

State: Vargas

Agency in charge of the proceedings: Brigade of Immediate Response of the PNB.

People implicated: Michel Alberto López.

...

The social service official of this hospital was denounced by relatives of three patients of asking for money in exchange for speeding up the process in the health center. He was dismissed and accused of “allegedly committing crimes related with misusing public officials’ benefits and leveraging relationships, foreseen and sanctioned by Articles 78 and 86 in the Anti-Corruption Law,” according to the local press.

Source: https://laverdaddevargas.com/extrabajador-del-periferico-acusado-de-extorsion-fue-enviado-a-el-rodeo/

Hospital I Roque

Alvarado, in Encontrados

State: Zulia

Agency in charge of the proceedings: National Police (PNB).

People implicated: Stanley Jaramillo, Yohana Tomasa and Vicmary Fernández.

...

The Police arrested two doctors on call and a supply saleswoman for charging 500,000 Colombian pesos (140 dollars) to a sergeant of the Armed Forces of Venezuela for a curettage, following a miscarriage. Doctors “had illegally seized the baby’s corpse as guarantee for the payment,” read the police report.

Source: https://epthelinkdos.online/occidente/zulia-medicos-cobran-500-000-pesos-a-joven-por-operarla-en-un-hospital/ http://jca.tsj.gob.ve/DECISIONES/2021/SEPTIEMBRE/589-23-C02-64875-2021-251-A-21.HTML

Maternity ward Julia Benítez

of Malpica Hospital

State: Carabobo

Agency in charge of the proceedings: Municipal Police of Guacara.

People implicate: Karla Ruíz.

...

The doctor was arrested for charging patients to perform c-sections in the health center.

Source: https://www.instagram.com/p/CaNj0SKvYBV/?igshid=MzRlODBiNWFlZA==

Non-specified

State: Barinas

Agency in charge of the proceedings: Public Ministry.

People implicated: Emilio José Osorio Rubio (arrest warrant issued against him).

...

Fake doctor accused of damages to an undetermined number of people in exchange for illegal fees.

Source: https://twitter.com/TarekWiliamSaab/status/1519324786345877504?s=19

Hospital Pedro Emilio Carrillo

State: Trujillo

Agency in charge of the proceedings: National Police (PNB).

People implicated: Juan Suárez and Karelis Montilla.

...

Suárez and Montilla requested 300 dollars from the accuser to operate on her brother. A “large amount of supplies stolen from the hospital” were confiscated in a raid to their homes, according to the official version.

Source: https://www.eluniversal.com/sucesos/127655/detiene-en-flagrancia-a-dos-medicos-por-cobrar-en-divisas-en-hospital-de-trujillo

Hospital José Antonio

Páez, in Guasdalito

State: Apure

Agency in charge of the proceedings: Scientific, Criminal and Forensic Science Corps (CICPC).

People implicated: Cándido Alfredo Martínez Rodríguez (68), María Yaritza Vequiz Rumbos (35), Ana Yumar Rodríguez Hernández (35) and Ivis Dubarly Páez (37).

...

Two gynaecologists and two surgeons were accused by the Office of the Attorney General of inappropriate and unjustified charges to users in need of surgery, also of selling surgical supplies that were of free distribution.

Source: https://twitter.com/TarekWiliamSaab/status/1537609389561065472?t=s3dJZrO1lzGwSc7BxU3GRQ&s=19

Hospital General, in Táriba

State: Táchira

Agency in charge of the proceedings: Police of Táchira.

People implicated: P. Somaza.

...

The Public Ministry arrested the traumatologist after several denunciations of inappropriate charges in exchange for surgery in the hospital. The doctor was accused of demanding money from patients to bypass the waiting list.

Source: https://puntodecorte.net/detienen-a-medico-senalado-de-cobrar-en-divisas/

Hospital General

Dr. Miguel Pérez Carreño

State: Distrito Capital

Agency in charge of the proceedings: National Police (PNB).

People implicated: Jaime José Godoy Azuaje.

...

The implicated doctor worked in this health center and charged 800 dollars to patients to perform surgery in the institution, according to the authorities.

Source: https://www.instagram.com/p/ChKmkn6LTn1/?igshid=MDJmNzVkMjY%3D

Hospital Central Universitario Antonio María Pineda

State: Lara

Agency in charge of the proceedings: Police of the state of Lara.

People implicated: Sergio Fernández Delmoral.

...

The implicated paramedic pretended to be a cardiologist, family members of a patient reported having been charged 400 dollars by a doctor to arrange surgery.

Source: https://www.elinformadorve.com/08/02/2023/sucesos/polilara-detiene-a-falso-medico-que-cobraba-para-gestionar-intervenciones-en-el-hcuamp/?fbclid=IwAR3uQpGM9B5LC0x_G1duqGaQWQTi-XI61hQtBFGDKZHvCj91qQVTS0QIPic&=1

Hospital Rafael

Medina Jiménez (Periferico, in Pariata)

State: Vargas

Agency in charge of the proceedings: Brigade of Immediate Response of the PNB.

People implicated: Michel Alberto López.

...

The social service official of this hospital was denounced by relatives of three patients of asking for money in exchange for speeding up the process in the health center. He was dismissed and accused of “allegedly committing crimes related with misusing public officials’ benefits and leveraging relationships, foreseen and sanctioned by Articles 78 and 86 in the Anti-Corruption Law,” according to the local press.

Source: https://laverdaddevargas.com/extrabajador-del-periferico-acusado-de-extorsion-fue-enviado-a-el-rodeo/

Moreover, Venzuelans have acquired the habit of not denouncing, and this phenomenon affects the healthcare sector as well, says Melendez, who also coordinates the regional chapter at OVV (Venezuelan Violence Observatory). He states that the Public Ministry requests people to denounce irregularities, but that people distrust institutions. “Citizens ponder their alternatives and think about the possible response given by the State while they try to solve their medical emergency. They believe it is more convenient to pay or to get their hands on the supplies needed to save the life of a relative. People may think that reporting could further damage the care provided to the patient or that care could be denied altogether.”

In April and May 2022, Nicolas Maduro admitted in three opportunities that there were persistent failures in the care provided by the public healthcare system, which ranged from lack of supplies and other irregularities. “I’m determined to bring down these mafias in hospitals and to have humane, free and quality medical services for the people (...) I want people to unmistakably denounce hospitals,” the Venezuelan ruler declared in an event. Back then, he ordered national healthcare authorities to break up corruption networks in hospitals. Despite his announcement, inappropriate charges remain a common practice, as proven by the cases of Braian, Carmen, Sara and the other patients that shared their experiences.

Paying has become the fastest way to access an operating room in a Venezuelan public hospital.

CREDITS

Editorial coordination: Nadeska Noriega Avila

Editorial support: team at CONNECTAS

Investigation and text: Nadeska Noriega Avila, Sheyla Urdaneta and Mayreth Casanova

Edition: Cesar Batiz and Sheyla Urdaneta

Reporting: Nadeska Noriega Avila, Mayreth Casanova, Sheyla Urdaneta, Ruth Lara Castillo, Glorimar Fernandez, Mairen Dona, Armando Altuve and Emily Moron Rodriguez | Databases: Mayreth Casanova and Nadeska Noriega Avila | Design and infographics coordination: ET y ARH / Collaboration: BT | Animation: Alexis Navarro | Audiopostales: Mayreth Casanova | Audiovisuals: Sebastian Crespo | Photography and video: Sebastian Crespo, Ruth Lara Castillo and Nadeska Noriega Avila | Audio: Eudes Narvaez, collaborator | Social media: Melissa Rodriguez

PAY OR DIE:

The Cost of Entering a Public Operating Room in Venezuela

an investigation by